How much do coastal mangroves contribute to their ecosystems as a climate solution? Researchers in Central America analyse their impact on health, biodiversity, and the economy

Belize, a small Central American country, is aiming to slow climate change, boost the economy and make communities safer – all while using natural methodologies to do so.

Quantifying the value of Belize’s coastal mangroves, a Stanford-led study analyses how much carbon they can hold, as well as the value they add to tourism and fisheries, and the protection they can provide against coastal storms and other risks.

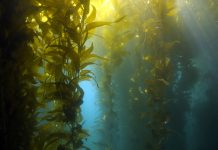

According to the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration, coastal mangroves stabilise the coastline, reducing erosion from storm surges, currents, waves, and tides.

Coastal mangroves stabilise the coastline

Additionally, the root system of mangroves also makes these forests attractive to fish and other organisms seeking food and shelter from predators – making them oxygen-producing biodiversity hotspots.

Overall, Stanford research finds that coastal mangroves provide an answer for Belize’s commitment to protecting the environment and the economy – mangrove forests are now to be rewilded across Belize to an area around the size of Washington, D.C., by 2030.

How much carbon do coastal ecosystems hold?

With the potential to curb human impacts – by reducing nutrients, organic matter, and wastewater inputs into coastal waterways – coastal ecosystems can reduce the amount of methane and nitrous oxide released to the atmosphere.

Nature-based solutions, such as locking up or sequestering carbon in mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marshes, help nations reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and also adapt to climate change.

However, many major coastal countries, including the U.S., frequently overlook these so-called blue carbon strategies, as calculating how much carbon wetlands and other coastal ecosystems can sequester and generating implementation strategies can be complicated.

Overall, blue carbon strategies have been found to maximize co-benefits for the economy, flood risk reduction, and other sectors; and in South America, research finds there already is a moderate CO2 uptake by coastal mangroves.

Carbon storage and sequestration in Belize and Mexico

Belizean policymakers and stakeholders quantified carbon storage and sequestration using land cover data from Belize and field estimates from Mexico.

This research analysed coastal flood risk reduction, tourism, and fisheries co-benefits by modelling related services – such as lobster breeding grounds – provided by coastal mangroves currently and under future protection and restoration scenarios.

The research found that in some areas, even small amounts of mangrove restoration can have big tourism and fisheries benefits.

However, total organic carbon sequestration is initially lower when restoring mangrove areas than when protecting existing forests because it takes time for carbon stocks to accumulate in the soil and biomass.

Denoting the negative aspects of coastal mangrove rewilding, the rate of increase for benefits other than carbon storage begins to decrease at a certain point as the mangrove area continues to increase.

Providing beneficial methods to coastal development strategy

From these findings, Belizean policymakers pledged to protect an additional 46 square miles of existing mangroves.

This brings the national total under protection to 96 square miles – to restore 15 square miles of coastal mangroves by 2030.

Predicting these inflexion points can help stakeholders and policymakers decide how to balance ecosystem protection when planning coastal development.

Belizean policymakers pledged to protect an additional 46 square miles of existing mangroves

While storing and sequestering millions of tons of carbon and boosting lobster fisheries by 66%, this research generates mangrove tourism worth several million dollars annually and reduces the risk of coastal hazards for at least 30% more people.

The numbers are significant for a country with a population smaller than Tulsa, Oklahoma, and a GDP equivalent to about 2% of New York City’s annual budget.

Study co-author Mary Ruckelshaus said: “Belize’s example, illustrating the practical ways nature’s many benefits can be spatially quantified and inform a country’s climate policy and investments, are now primed to be scaled around the world with development banks and country leaders.”

Study lead author Katie Arkema added: “The U.S. has one of the largest coastlines in the world and extensive wetlands. This paper offers an approach we could use for setting evidence-based climate resilience and economic development goals.”