Donald A. Mahler from the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and Clinical Resource Center of the Alpha-1 Foundation and Valley Regional Hospital, on behalf of the CHEST Foundation, provides an expert view on shortness of breath (dyspnea)

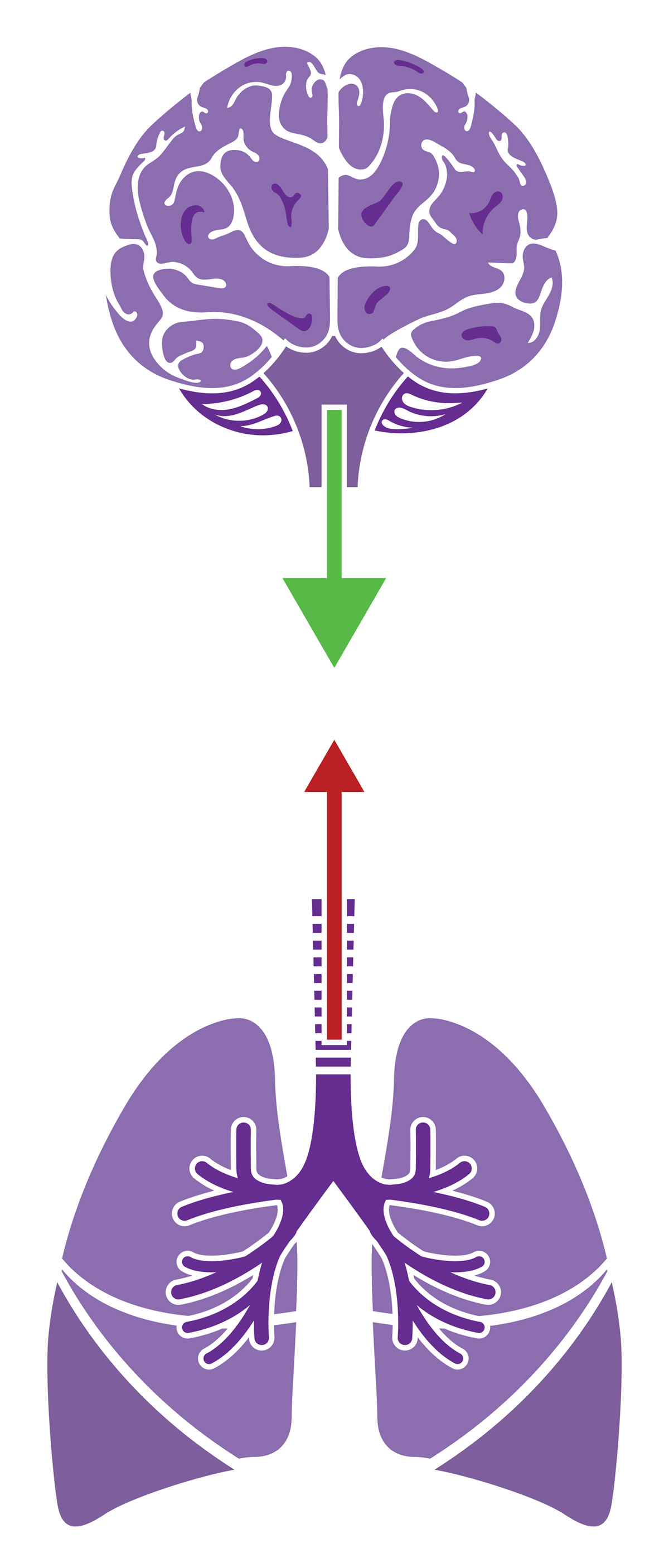

A healthy person breathes 12-14 times every minute without a thought. Breathing is automatic as the medulla in the brain stem sends electrical signals to the respiratory muscles to control how often and how deep to breathe. Receptors in the respiratory system provide information about how the lungs are working to the brain. Based on a neurobiological model, shortness of breath results from an imbalance or mismatch between the demand to breathe and the ability to breathe.

Dyspnea (dys – difficult; pnea – breathing) is the medical word for shortness of breath. The three major qualities are: work/effort of breathing; chest tightness; and unsatisfied inspiration. Those who experience breathing difficulty often report the feeling as, “I am short of breath,” or “I feel like I can’t get enough air in.” These experiences are a warning signal that the interaction between the respiratory system and the brain is not working properly.

Causes of shortness of breath

Shortness of breath is frequently classified by how it develops – acute (sudden onset) and chronic (over weeks to months). The most common causes of acute and/or chronic dyspnea are diseases of the heart (congestive heart failure, valve dysfunction and cardiomyopathy), of the lung [asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and interstitial lung disease], of the pulmonary blood vessels (pulmonary embolism and pulmonary hypertension) and advanced cancer.

Other possibilities for chronic shortness of breath include anaemia, deconditioning (“out of shape”) and psychological conditions, such as anxiety or depression. Although a low oxygen level in the body increases ventilation and causes shortness of breath, a person may experience breathing difficulty despite a normal oxygen level.

Risk factors for heart disease include smoking, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, physical inactivity and a family history of heart disease at an early age. Risk factors for lung disease are smoking, inhalational exposures both occupational and recreational and a family member with a specific lung condition. Deconditioning is a direct result of reduced physical activities due to a sedentary lifestyle or possibly an illness, injury, or surgery.

The diagnosis

For evaluation of acute shortness of breath, the person typically goes to an emergency department, whereas a complaint of chronic breathing difficulty is usually addressed in an out-patient facility. Assessment by a health-care professional includes a medical history, physical examination and appropriate testing that includes pulse oximetry.

For acute shortness of breath, a chest x-ray and electrocardiogram are essential. Two blood tests can be helpful. Prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (pro-BNP), secreted by the myocardium, is elevated in heart failure; and D-dimer, a product of fibrin degradation in the blood, is elevated with pulmonary embolism. Computed tomography (CT) scanning may be considered for further evaluation.

For chronic shortness of breath, pulmonary function testing and a chest x-ray are typically ordered. Other diagnostic testing may include a complete blood count, an echocardiogram and cardiopulmonary exercise depending on the individual’s specific features.

Getting treatment

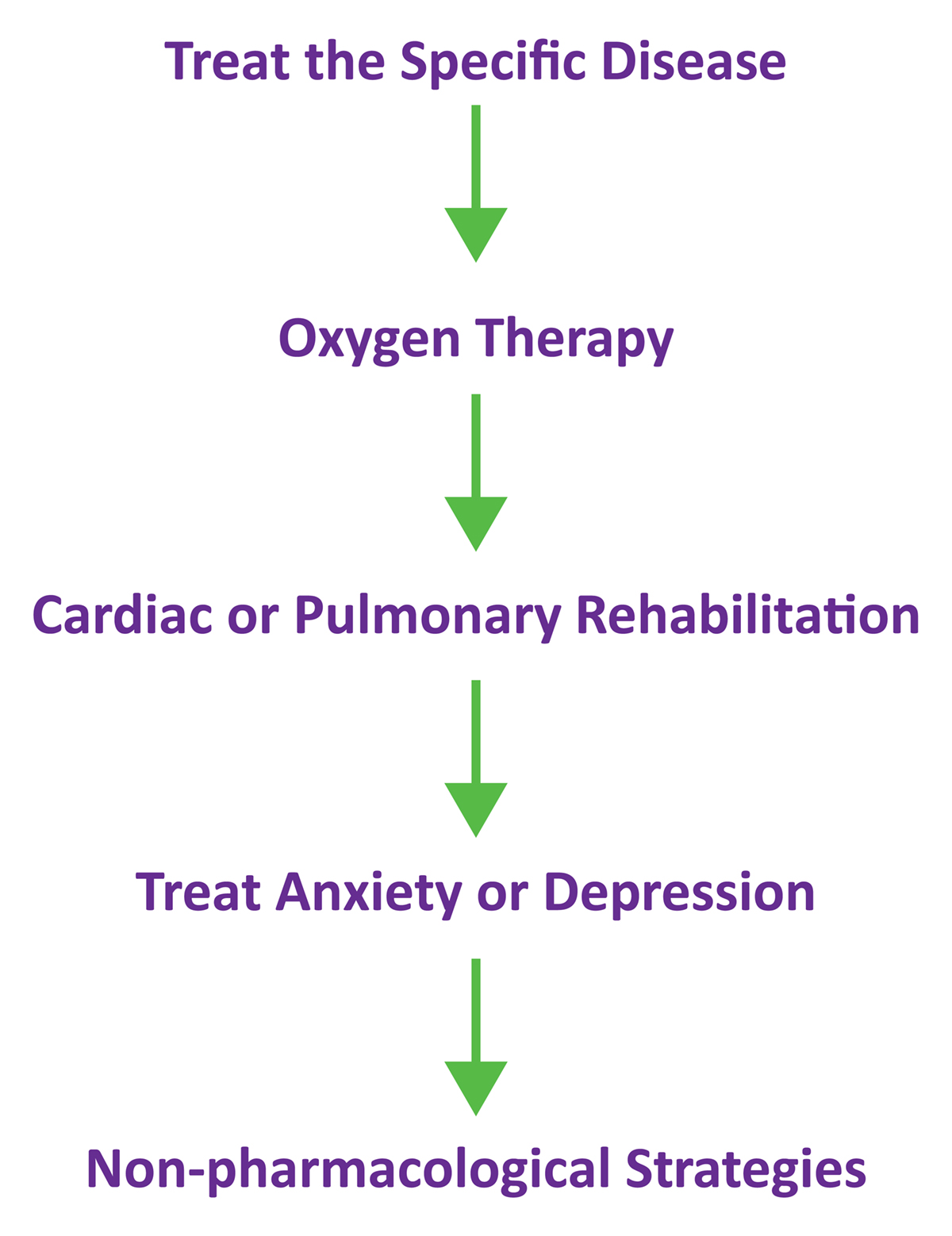

The following diagram provides a general approach to relieving shortness of breath.

Medications are usually prescribed as treatment for the specific disease that can relieve breathing difficulty. Oxygen therapy is provided if the individual’s oxygen saturation is 88% or below. As many individuals with chronic heart or lung diseases are inactive due to their shortness of breath, referral to a cardiac or pulmonary rehabilitation program is important.

Studies show that supervised exercise training will relieve shortness of breath, improve quality of life and enhance functional ability. Anxiety and/or depression should be treated to improve an individual’s mental health which may also alleviate breathing difficulty.

Non-pharmacological strategies for relief of dyspnea include a fan blowing air on the face, pursed lips-breathing (puckering the lips during exhaling in those with asthma and COPD), the leaning forward position with forearms resting on the thighs or hands on a shopping cart, listening to music, meditation, mindful breathing (an awareness of each breath so that the focus is on the present and breathing becomes relaxed) and yoga.

The priorities for future research

The following recommendations are proposed to advance the treatment of shortness of breath.

- Educate the public about the importance of shortness of breath as a symptom of heart and lung disease. It should not be considered a consequence of aging.

- Develop a new scale or instrument for individuals to rate shortness of breath related to daily and recreational activities. An ideal scale would be valid, reliable and responsive to treatments, would be used in clinical practice and would be accepted by regulatory agencies for approval of new therapies.

- Provide research support to develop new treatments.Possibilities include acupuncture, chest wall vibration and a custom engineered opioid that does not depress the respiratory drive to breathe.

References

1 Parshall MB, Schwartzstein RM, Adams, L, Banzett RB, Manning HL, Bourbeau J, et al. An official American Thoracic Society statement: Update on the mechanisms, assessements and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 185:435-452.

2 Mahler DA, O’Donnell DE (Editors). Dyspnea: Mechanisms, Measurement and Management, 3rd Ed. 2014. CRC Press (imprint of Taylor and Francis Group, LLC), Boca Raton, FL.

3 Mahler DA. Evaluation of dyspnea in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med 2017; 33:503-521.

Donald A. Mahler, M.D.

Emeritus Professor of Medicine, Geisel School of Medicine

at Dartmouth, Director of Respiratory Services.

Director of Clinical Resource Center of the Alpha-1 Foundation

Valley Regional Hospital.

www.twitter.com/Alpha1UKSupport

CHEST Foundation

Tel: +1 224 521 9527

https://foundation.chestnet.org/