Fact or science fiction? A groundbreaking study has shown that human brain cells in a dish can play the video game Pong

It may sound like a scene from a science fiction film, but no it’s actually true – Melbourne-led scientists have shown that 800,000 brain cells living in a dish can perform goal-directed tasks, like playing the video game Pong.

The results of the groundbreaking study are published today in the journal Neuron.

The next stage of the study is to find out what happens when their DishBrain is affected by medicines and alcohol.

Lead author Dr Brett Kagan, who is Chief Scientific Officer of biotech start-up Cortical Labs commented: “We have shown we can interact with living biological neurons in such a way that compels them to modify their activity, leading to something that resembles intelligence.”

“DishBrain offers a simpler approach to test how the brain works and gain insights into debilitating conditions such as epilepsy and dementia,” adds Dr Hon Weng Chong, Chief Executive Officer of Cortical Labs.

This is the first time that cells have been stimulated in a structured and meaningful way

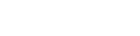

For some time scientists have been able to mount neurons on multi-electrode arrays and read their activity, but this is the first time that cells have been stimulated in a structured and meaningful way.

In truth, we don’t really understand how human brain cells work

“In the past, models of the brain have been developed according to how computer scientists think the brain might work,” Kagan says. “That is usually based on our current understanding of information technology, such as silicon computing.

“But in truth we don’t really understand how the brain works.”

By building a living model brain from basic structures in this way, scientists and researchers will be able to experiment using real brain function rather than flawed analogous models like a computer.

Kagan and his team hope to gain insight into how the DishBrain is affected by alcohol.

“We’re trying to create a dose response curve with ethanol – basically get them ‘drunk’ and see if they play the game more poorly, just as when people drink,” says Kagan.

The potential for lab-grown human brain cells is much greater than playing a video game

That scientists have been able to show human brain cells in a dish playing a video game really is revolutionary and changes the game. It opens up new ways of thinking and understanding what is happening with the brain.

“This new capacity to teach cell cultures to perform a task in which they exhibit sentience – by controlling the paddle to return the ball via sensing – opens up new discovery possibilities which will have far-reaching consequences for technology, health, and society,” says Dr Adeel Razi, Director of Monash University’s Computational & Systems Neuroscience Laboratory.

“We know our brains have the evolutionary advantage of being tuned over hundreds of millions of years for survival. Now, it seems we have in our grasp where we can harness this incredibly powerful and cheap biological intelligence.”

Could human brain cells be an alternative to animal testing?

Animal testing is a deeply contentious subject and opinion is divided across the scientific community and wider population.

Therefore it is welcome news for many that these findings also raise the possibility of creating an alternative to animal testing when investigating how new drugs or gene therapies respond in dynamic environments.

“We have also shown we can modify the stimulation based on how the cells change their behaviour and do that in a closed-loop in real time,” comments Kagan.

To conduct this particular experiment, the Melbourne-based team took mouse cells from embryonic brains, and some human brain cells derived from stem cells and grew them on top of microelectrode arrays. This allowed scientists to stimulate them and read their activity.

Electrodes on the left or right of one array were fired to tell Dishbrain which side the ball was on, while the distance from the paddle was indicated by the frequency of signals. Feedback from the electrodes taught DishBrain how to return the ball, by making the cells act as if they themselves were the paddle.

“We’ve never before been able to see how the cells act in a virtual environment,” says Kagan. “We managed to build a closed-loop environment that can read what’s happening in the cells, stimulate them with meaningful information and then change the cells in an interactive way so they can actually alter each other.”

“The beautiful and pioneering aspect of this work rests on equipping the neurons with sensations — the feedback — and crucially the ability to act on their world,” says co-author Professor Karl Friston, a theoretical neuroscientist at UCL, London.

“Remarkably, the cultures learned how to make their world more predictable by acting upon it. This is remarkable because you cannot teach this kind of self-organisation; simply because — unlike a pet — these mini brains have no sense of reward and punishment,” he says.

“The translational potential of this work is truly exciting: it means we don’t have to worry about creating ‘digital twins’ to test therapeutic interventions. We now have, in principle, the ultimate biomimetic ‘sandbox’ in which to test the effects of drugs and genetic variants – a sandbox constituted by exactly the same computing (neuronal) elements found in your brain and mine.”

The research supports Professor Friston’s “free energy principle”

“We faced a challenge when we were working out how to instruct the cells to go down a certain path. We don’t have direct access to dopamine systems or anything else we could use to provide specific real-time incentives so we had to go a level deeper to what Professor Friston works with: information entropy – a fundamental level of information about how the system might self-organise to interact with its environment at the physical level.

“The free energy principle proposes that cells at this level try to minimise the unpredictability in their environment.”

Kagan says one exciting finding was that DishBrain did not behave like silicon-based systems. “When we presented structured information to disembodied neurons, we saw they changed their activity in a way that is very consistent with them actually behaving as a dynamic system,” he says.

“For example, the neurons’ ability to change and adapt their activity as a result of experience increases over time, consistent with what we see with the cells’ learning rate.”

The discovery is only the beginning

Chong says he was excited by the discovery but emphasises that it is only the beginning.

This is brand new, virgin territory

“This is brand new, virgin territory. And we want more people to come on board and collaborate with this, to use the system that we’ve built to further explore this new area of science,” he says.

“As one of our collaborators said, it’s not every day that you wake up and you can create a new field of science.”