Here Professor Richard Beardsworth, University of Leeds, continues his series on progressive state leadership by suggesting how it can spearhead the political vision of sustainable development

In previous articles on progressive state leadership [my FCDO vision and COP26 articles in OAG], I have spoken of the governmental need explicitly to link the climate agenda (carbon neutrality by 2050) with the sustainable development agenda (Agenda 2030) and suggested that this link provides a forward-looking political vision that is, at one and the same time, domestic and international. Underpinning this argument are five concerns:

- Political leadership by climate-progressive states constitutes a necessary condition of success in climate action; without this leadership at the national level, the ability to transform the system will prove impossible. We need ‘the master’s tools’ to mend ‘the master’s house’.

- While the eradication of extreme poverty remains a moral and political imperative for all leaders (in government and civil society), previous distinctions between the ‘North’ and the ‘South’ are being unmade by the emerging geopolitical order, the new relative weightings of national economies, rising domestic inequality and the increase in extreme climate events.

- It is within the framework of general sustainability that solidarity among less vulnerable and more vulnerable countries and populations is found. It is further within this framework that cognitive, ethical and social ‘best practices’ regarding future relations between human communities and nature can be rehearsed and shared (foremost: food production, distribution and consumption).

- Agenda 2030 – the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a whole – offers a rights-based vision of development for all countries that is based on the increasing importance of partnerships (SDG17) among more vulnerable and less vulnerable countries and on shared leadership among them.

- Focusing on the United Kingdom, the recent amalgamation of the FCO and DFID into the FCDO explicitly links foreign policy and diplomacy to development [my FCDO article in OAG]. Despite November’s announcement that ODA will be reduced to 0.5% of GNI until further review, this framework of sustainability needs to be addressed comprehensively across ministerial departments. If progressive state leadership on the two agendas of climate and sustainability is to prove possible in this decade, then government must use the power of the state to integrate sector-wide policies at both the national level and between the national and international levels. No other domestic or international actor can do this.

Budget

The announcement of the ODA budget cut does not augur well for this political vision. New budgetary restrictions, as well as forthcoming tax increases that address the COVID financial deficit, suggest a period of retrenchment that will, whatever the political rhetoric, break links among economic recovery, ‘green industrialization’, and international solidarity. That said, climate realities will escalate, not subside, and people’s experiences both within the North and the South and across the North and the South will be increasingly affected by them. Among worse alternatives, a progressive response to climate realities requires political vision. The remaining part of this article rehearses the terms of this vision further. It does not offer expertise on particular points (there are very many now who can); it wishes to ‘join the dots’ in such a way that the above political framework becomes sharper.

Responsibility towards the climate informs many of the SDGs and is explicitly taken up in SDG13 (to take urgent action to combat climate change) and its five targets (resilience, policy-integration, knowledge and capacity-building, financial transfers, management-building in least developed countries). There is evidently a logical and practical continuum between climate action and more general sustainability practices. That said, in order that the political vision on linkage between the climate and sustainability agendas has national and international political traction and effect, the agendas need also to be kept separate. Within the width and depth of a political vision on sustainable development for all, delimited space for the role of the climate sciences and for science-based climate mitigation strategies remains vital.

Only with this delimitation can imminent climate mitigation targets be achieved. The accompanying risk that technology-based solutions replace nature-based solutions must nevertheless be clearly rehearsed within this vision, and this risk must not undermine the need for political action now. With this delimitation, the inextricable relation between climate action and general sustainability practices can be affirmed.

Climate, economy and justice

The SDGs rightly bring together the climate, the economy, and justice. One cannot, for example, separate the transition to clean energy either from those still working within the fossil fuel economy or from those who have immediate sustenance needs. If one does, political resistance and political repercussion at national and international levels will be large. The political vision of sustainable development for all should be based, simultaneously, on a platform of response to climate realities and on fostering systemic change: a reformed capitalism responsive to society’s needs, new structures of representation and power across the world, behavioural change.

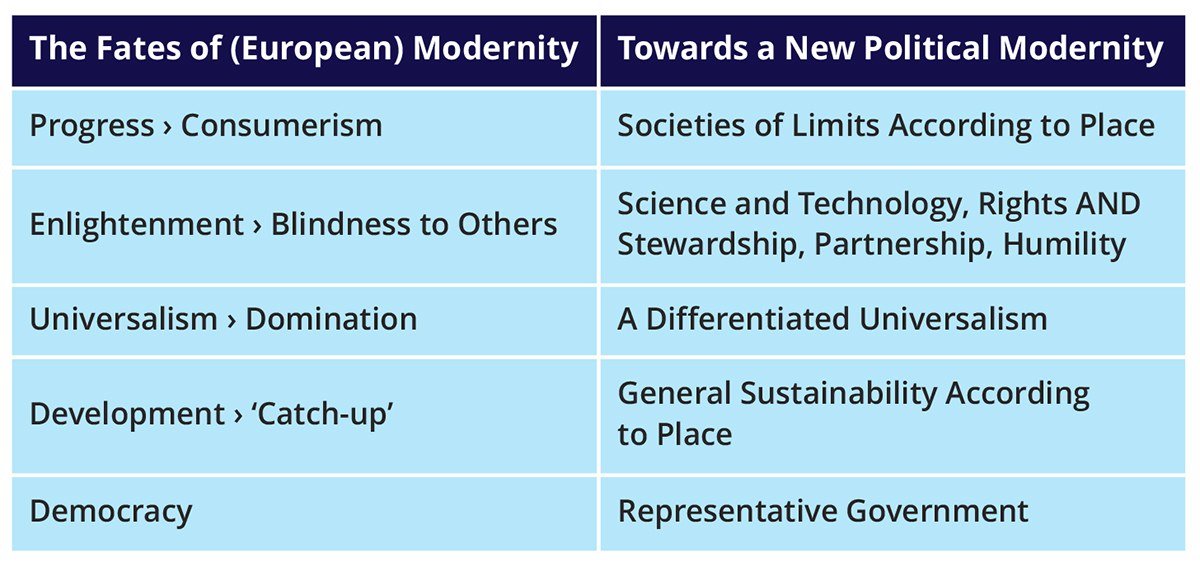

Several terms have been formulated in the academy to define the profound transformations now affecting the currency of modern life. ‘Postmodernity’ and the ‘Anthropocene’ are two that mark strongly the historical shift underway. Given the importance of science, technology, rights-based action, the state and markets to address climate change and forge pathways towards general sustainability, it would be politically wrong, I suggest, to replace the term ‘modernity’. The political vision of sustainable development requires an intellectual and historical frame within which to embed itself.

It needs one that frames the important advances in the last three hundred years of modernity, rehearses clearly modernity’s negative underbelly, and re-organizes it within a wider, but context-specific lens. The table below suggests one possible formulation.

If linking the climate agenda to the sustainable development agenda can be done within this broader frame, then a sharper political vision of sustainable development will emerge. Political leadership can then work with a substantive sense of what a progressive orientation that bridges national and global imperatives entails.

*Please note: This is a commercial profile

Contributor Profile

Editor's Recommended Articles

-

Must Read >> The leadership challenge of COP26, 2021

-

Must Read >> What is progressive state leadership today?