Tracey Wade from Flinders University highlights the benefits of early interventions for eating disorders. She notes that brief interventions during waiting periods can boost treatment completion rates, and early symptom improvements can lead to better outcomes

What does early intervention look like?

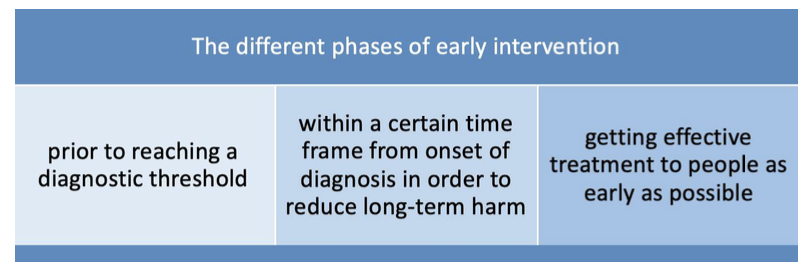

The term ‘early intervention’ has been used in different ways, but overall refers to offering intervention as early as possible to minimise long-term adverse consequences for health. In mental health, it can occur at three different points, as summarised in the Figure.

First, early intervention can refer to interventions for young people before they reach the threshold for a traditional major psychiatric diagnosis, but where distress, functional impairment and warning signs of mental illness are present. (1) Early intervention at this time point is seen as crucial to preventing or reducing the severity of a full-threshold disorder. (2)

Second, early intervention may refer to evidence-based treatment occurring within a certain time frame from the onset of symptoms, dictated by evidence that much of the harm of the disorder can be obviated in this period. For example, in eating disorders, given that six months of underfeeding in the Minnesota study required up to two years to recover normal strength, early intervention for eating disorders designed to prevent the most harm might require treatment within weeks of onset. Typically, however, the accepted time frame in eating disorders is within three years of onset. (3)

Third, early intervention can be defined as working toward the shortest possible duration of untreated eating disorder (DUED). It means getting effective treatment to people as early as they present for treatment, regardless of the duration of the eating disorder, rather than placing them on a lengthy waitlist, where motivation to change may wane.

Intervention at the earliest possible point

It is this latter group on which this article focuses. People with eating disorders are highly ambivalent about seeking help, and longer times on a waitlist reduce the chances that they will engage in, or complete, treatment when it is offered, and increases the likelihood of adverse events, including mortality for people with anorexia nervosa.

Our research has found that offering people with eating disorders some type of brief intervention while they are on the waitlist, that does not deflect resources from treatment, significantly increases the likelihood that they will complete subsequent treatment. (4)

Our research has also found that utilisation of unguided single session interventions can start the work of early change before treatment even commences. (5) This information about early change can also be used to match people to an appropriate intensity of treatment.

Maximising change over the early window of opportunity in treatment

In cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) for psychological disorders, we see strong improvement in symptom severity within the first eight sessions, and then symptom reduction continues but at a slower pace. (6) This early decrease in eating disorder symptoms, currently experienced by about 50% of people, places people in a significantly better position to have a good outcome of treatment. We also know that the number of patients who show early change is at least partially a reflection of our performance as clinicians. (7) The important questions to consider moving forward, to produce better outcomes for our therapies, include:

- How can we increase the number of patients who experience early change?

- How can we help clinicians become better at helping patients make this early change?

Our current research

Our research, funded by a National Mental Health and Research Council Investigator Grant (2025665), is evaluating the first and third areas of early intervention described in the Figure. This first area has been described in previous articles. (2,5) Our work in the third area encompasses not just the use of a single session intervention (Behavioural Activation) before CBT commences in order to kick-start early change, but also the use of sessional measures of progress shared in each session with the patient (shown to improve performance of therapists), and a review of progress at the fourth session. If early change is not present, we consider (i) obstacles to change with the patient and (ii) which of the nine augmentation topics may best address these. The augmentation will then be incorporated into ongoing therapy. (8)

It is our hope that our results will show we can achieve better remission rates for patients by thoughtfully utilising current evidence to individualise treatment.

References

- McGorry, P. D., & Mei, C. (2018). Early intervention in youth mental health: progress and future directions. Evidence-based Mental Health, 21, 182–184.

Doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2018-300060 - Wade, T. D. (2025). “Consideration of key issues in positioning early intervention for eating disorders”, Open Access Government, April 2025, pp. 156-157. Available at: https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/article/consideration-of-key-issues-in-positioning-early-intervention-for-eating-disorders/188763/ Doi: https://doi.org/10.56367/OAG-046-11724

- Allen, K. L., et al. (2023). A framework for conceptualising early intervention for eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 31, 320–334. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2959

- Keegan, E., Waller, G., Tchanturia, K., & Wade, T. D. (2024). The potential value of brief waitlist interventions in enhancing treatment retention and outcomes: a randomised controlled trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 53, 608–620. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2024.2351867]

- Wade, T. D. (2024).”Early intervention for eating disorders”, Open Access Government January 2025, pp.174-175. Available at https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/article/early-intervention-for-eating-disorders/185166/ Doi: https://doi.org/10.56367/OAG-045-11724

- Klein, T., et al. (2024). Dose-response relationship in cognitive behavioral therapy for depression: A nonlinear metaregression analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 92, 296–309. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000879

- Saxon, D., Firth, N., & Barkham, M. (2017). The relationship between therapist effects and therapy delivery factors; Therapy modality, dosage, and non-completion. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 44, 705-715. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0750-5

- Wade TD, Edney L, Pellizzer M, Pennesi J-L, Radunz M, Trott M, Zhou Y, Waller G. (2025). Study protocol for a pre-registered randomized open-label trial of ten-session cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT-T) for eating disorders: Does stratified augmented treatment lead to better outcomes? BMJ Open, 15(4), e099212. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2025-099212