Business survival in an era of converging crises

In October 2024, Hurricane Helene devastated Buncombe County, North Carolina, claiming over 70 lives in what was once considered a climate haven. Asheville, nestled in the temperate Blue Ridge Mountains and far from coastal storm surges, had represented hope – a refuge from climate chaos. Now, its valleys lie ravaged by unprecedented floods, shattering a dangerous illusion: that we can find safe havens from Earth’s destabilizing systems.

This stark reality exemplifies what scholars now recognize as the “polycrisis” – not isolated challenges but interconnected crises that amplify each other in complex feedback loops. Climate change intensifies water scarcity, which strains food production, triggering social unrest and economic instability, which in turn hampers our ability to address climate change. Each crisis magnifies the others, creating cascading effects that reverberate through Earth’s systems. The term “polycrisis” captures a critical insight: our challenges are not merely multiple separate crises occurring simultaneously, but mutually reinforcing phenomena that can only be understood and addressed as an interconnected whole.

For business leaders, this interlinked reality means no industry stands immune. Supply chains fracture under extreme weather events. Resource scarcity drives price volatility. Social instability disrupts markets. Physical infrastructure faces unprecedented stresses from extreme temperatures and precipitation. Insurance models break down as “hundred-year events” become regular occurrences. The challenge isn’t saving the planet – it’s ensuring the continued viability of human civilization and the businesses that operate within it.

In this context, Sustainable Strategic Management (SSM) emerges not as an optional approach but as a coevolutionary necessity for business survival and success. Where traditional strategic management focuses on optimizing firm performance within relatively stable market conditions, SSM recognizes that business success now depends on the health of social and ecological systems that are rapidly changing – often in non-linear, unpredictable ways. The strategic question shifts from “How can we outcompete others?” to “How can we help regenerate the systems upon which all prosperity depends?”

Earth as a complex system: Coevolutionary theory

James Lovelock’s Gaia Theory provides a powerful framework for understanding our predicament. Earth operates as a single, self-regulating organism, with complex feedback systems maintaining conditions suitable for life. These systems have kept our planet habitable for billions of years through asteroid impacts, solar radiation fluctuations, and mass extinctions. The critical insight is that life doesn’t merely adapt to planetary conditions – it actively creates and maintains them through interlocking biogeochemical cycles that regulate everything from atmospheric composition to ocean acidity.

Scientists warn that humanity has already crossed six of the nine planetary boundaries that maintain Earth’s stability and support human life, including climate change and biodiversity loss. These boundaries are not arbitrary lines drawn by environmentalists but thresholds beyond which Earth systems may shift into new states incompatible with human civilization as we know it. Our ecological footprint shows we’re consuming resources at a rate requiring 1.7 Earths – a clear sign we’re overwhelming natural systems.

The relationship between business and Earth’s systems is coevolutionary – each influences and shapes the other in an ongoing dance of adaptation. However, this coevolution has become dangerously imbalanced. Business activities have transformed Earth systems at an unprecedented rate, while our strategic responses remain rooted in outdated paradigms that fail to recognize our embeddedness within these systems. Our economic models still treat nature as an external source of “resources” and a sink for “waste” rather than a living system upon which all value creation depends.

This coevolutionary perspective reveals why incremental approaches to sustainability fall short. The feedback loops within Earth’s systems are accelerating, creating non-linear changes that can quickly overwhelm linear responses embedded in traditional strategic management. For instance, climate tipping points like Arctic sea ice loss and permafrost thaw can trigger self-reinforcing cycles that continue regardless of subsequent emission reductions. Our strategic responses must match this systemic, non-linear reality, moving beyond gradual improvements to fundamental transformations in how we understand value creation.

Liminality: Between economic paradigms

We currently occupy a liminal space – a threshold between two economic paradigms that fundamentally shape how we understand business’s relationship to the natural world. Anthropologists describe liminality as the ambiguous state between familiar structures, where old rules no longer fully apply but new ones haven’t yet solidified. This concept aptly describes our current economic moment – a time of both great peril and possibility.

The dominant neoclassical economic paradigm treats the economy as a closed system, separate from nature. It assumes infinite resources, unlimited growth potential, and treats environmental and social impacts as “externalities.” Market mechanisms are considered sufficient to address any constraints, and value is narrowly defined as financial returns to shareholders. This paradigm emerged during an era of a relatively empty world (few people, abundant resources) and has reached its logical conclusions in concepts like shareholder primacy, quarterly earnings focus, and GDP growth as the primary measure of societal success.

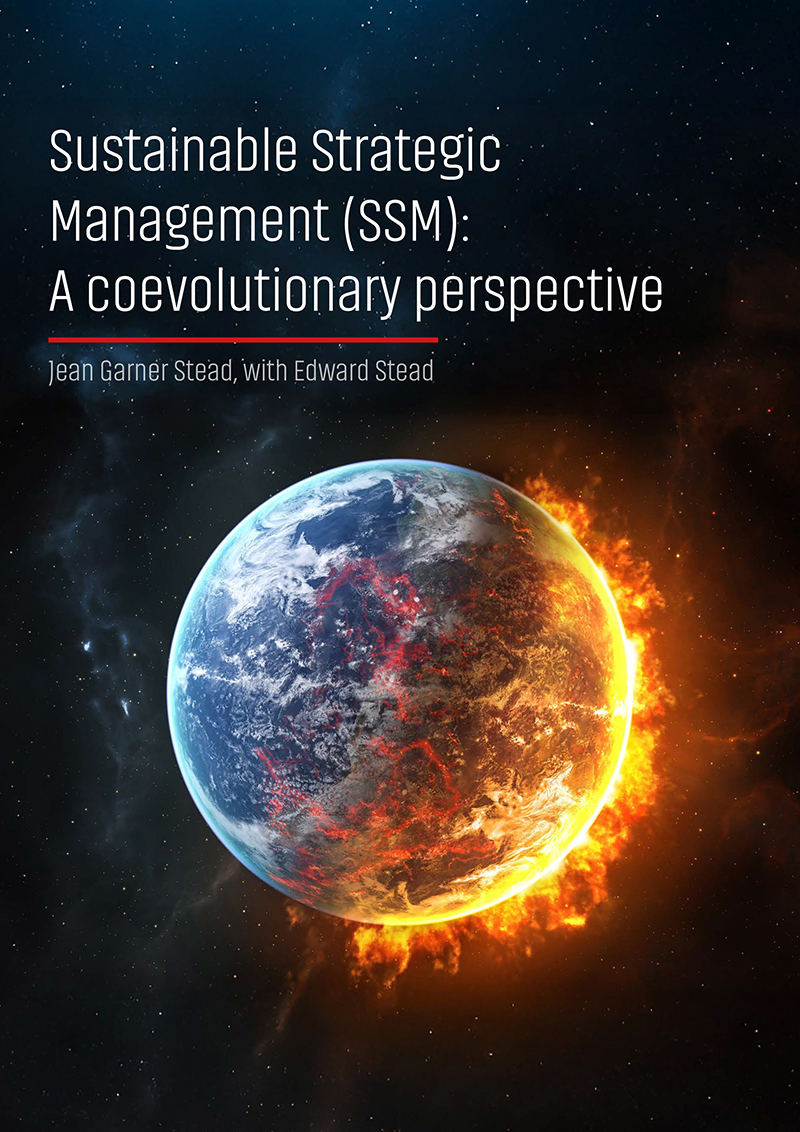

In contrast, ecological economics recognizes the economy as a wholly contained subsystem of the finite biosphere. It acknowledges planetary boundaries, views resources as limited, and considers economy-environment interactions as central rather than external. Value is understood more broadly to include the maintenance of natural and social capital. This emerging paradigm better reflects our current reality of a “full world” where human activities significantly impact all Earth systems, and where maintaining those systems becomes a precondition for continued human flourishing, including economic prosperity. Figure 1 demonstrates the open system thinking of ecological economics.

This liminal period creates both unprecedented threats and opportunities for strategic leaders. Traditional strategic management emphasizes finding the right “fit” between environmental opportunities and threats and organizational strengths and weaknesses. This approach assumes a relatively stable environment where competitive advantage comes from either effectively deploying resources that can be sustained over time or positioning the firm in the appropriate industry structure within fixed industry boundaries.

However, coevolutionary dynamics reveal this model as fundamentally flawed. The relationship between the organization and environment is not static but constantly changing, coevolving. As Earth’s systems shift in response to human activities, and human systems shift in response to environmental changes, the very nature of strategic “fit” becomes dynamic rather than static. The concept of competitive advantage must expand to include not just advantages within industry boundaries, but advantages derived from contributing to system health across traditional boundaries. This requires a transformation in how we understand strategy – from static positioning to dynamic participation in system coevolution.

The liminal phase also challenges traditional industry definitions and competitive frameworks. Consider the automotive industry’s transformation toward mobility services, the energy sector’s evolution from fossil fuel extraction to integrated renewable systems, or the shift in agriculture from commodity production to regenerative food systems. In each case, industry boundaries blur as organizations recognize that the wicked problems of sustainability cannot be addressed within traditional structures. The liminal period demands new forms of collaboration – even among traditional competitors – to create the technical, social, and institutional innovations needed for system transformation.

From resource-based view to flourishing circularity

Jay Barney’s Resource-Based View fundamentally assumes a closed economic system where firms compete primarily through controlling scarce resources and capabilities that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN). This view inherently treats social and natural capital as either infinite sources (of raw materials) or infinite sinks (for waste) – assumptions proving catastrophically incorrect as planetary boundaries are breached.

The circular economy concept attempted to address these limitations by promoting resource reuse and recycling. However, mere circularity without regeneration simply delays environmental degradation rather than reversing it. A circular phone made with conflict minerals in exploitative labor conditions and powered by coal-generated electricity remains fundamentally unsustainable, regardless of how efficiently its materials are recovered and reused. Flourishing circularity transcends this limitation by integrating regenerative principles that enhance rather than merely maintain capital stocks.

Where traditional economics treats social and environmental impacts as externalities – costs or benefits not reflected in market prices – flourishing circularity places these impacts at the center of resource assessment. Natural capital (ecosystems, biodiversity, climate stability) and social capital (trust, community resilience, cultural knowledge) become core strategic resources to be regenerated rather than merely exploited or preserved. This represents a profound shift in strategic thinking – from seeing nature and society as contexts for business activity to recognizing them as foundational sources of all value creation.

This shift recognizes that in a polycrisis era, competitive advantage increasingly derives not from resource control but from a firm’s ability to regenerate the systems upon which all business ultimately depends. The question becomes not just “What resources do we control?” but “How do our activities enhance the social and natural systems that sustain us?” This means reconceptualizing strategic value creation – from extraction to regeneration, from exploitation to flourishing, from static to dynamic capabilities.

Core competencies for flourishing circularity

Flourishing circularity demands new organizational competencies that fundamentally reorient how firms interact with social and natural capital. These competencies transform traditional “externalities” into central strategic considerations:

Regenerative Approaches to Social Capital:

Beyond corporate social responsibility, regenerative social capital builds trusting relationships with communities, employees, and value chain partners that increase resilience and innovation potential. Firms develop capabilities to measure and enhance their social handprint (positive impacts) rather than merely reducing negative impacts. Companies like Patagonia demonstrate this through initiatives that build thriving communities, restore environments, and advocate for policy changes that enhance social and ecological well-being.

Regenerative Approaches to Natural Capital:

Similarly, firms develop capabilities to enhance biodiversity, soil health, water systems, and atmospheric stability – not just minimize damage to them. This involves designing products and processes that mimic natural systems, leaving ecosystems healthier than before. For example, agricultural practices that sequester carbon while enhancing soil microbiome diversity simultaneously address climate challenges and improve productivity.

Systems Thinking and Cross-Boundary Collaboration:

The complexity of the polycrisis requires thinking beyond organizational boundaries. Firms build competencies in systems mapping and collaborative problem-solving across traditional industry divisions. This includes developing platforms for pre-competitive collaboration on shared challenges and innovating business models that create value through system regeneration.

These competencies translate into competitive advantages as stakeholders increasingly favor organizations that enhance system health. Early adopters of regenerative practices often discover cost savings, innovation opportunities, enhanced resilience, and brand differentiation that traditional methods would overlook.

Assessment Methods for Flourishing Circularity

Traditional resource assessment tools fail to capture the dynamic nature of resources in a polycrisis context. Traditional footprint analysis, which collects data along the value chain, operates under the assumption of a static environment. In contrast, coevolving footprint analysis extends beyond conventional environmental assessment by recognizing the dynamic interplay between organizational activities and ever-changing social and ecological systems – capturing how businesses both shape and are shaped by their broader contexts. It acknowledges shifting organizational boundaries and measures both current and potential future impacts, helping organizations anticipate emerging risks and opportunities.

This analysis develops coevolving SSM dynamic capabilities – abilities to sense, seize, and transform in response to rapidly changing conditions. These include anticipatory skills (identifying emerging crises), adaptive capacity (modifying strategies in real-time), and transformative potential (rethinking business models when necessary). The insights gathered enable firms to identify leverage points where small interventions yield disproportionate system benefits, creating strategic priorities for resource allocation and capability development that regenerate rather than deplete the systems upon which all value ultimately depends.

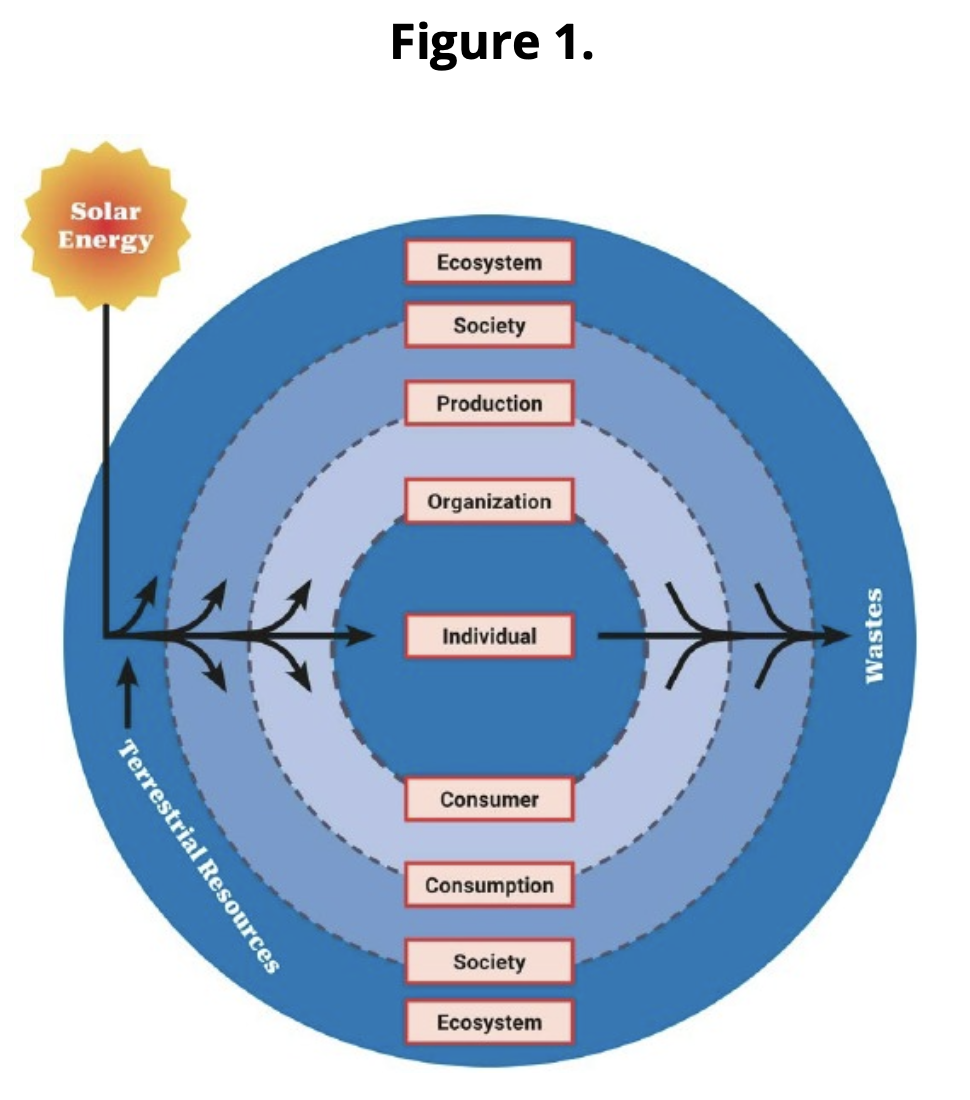

The strategic coevolution of SSM

Sustainable Strategic Management represents a coevolutionary progression that parallels the journey organizations must undertake – from closed to open systems thinking, from competitive to corporate/ enterprise perspectives, and from efficiency to effectiveness in creating ecological and social value. This progression isn’t linear but involves continuous adaptation as organizations and environments mutually influence each other, creating new possibilities and constraints that further drive coevolution.

This coevolutionary journey manifests in strategic approaches that expand in scope and impact, ultimately requiring a spiritual transformation in how we understand the purpose of business: