Germaine A. Hoston of the University of California, San Diego, demonstrates the influence of Neo-Confucianism on European idealism and Marxist revolutionary thought

The notion that there are fundamental differences between Western and non-Western worldviews persists in the scholarly and popular literature on international relations. This idea was reinforced by the September 11 terrorist attacks originating from non-Western societies.

Influences on Eastern and Western philosophies

Are Eastern and Western philosophies really incommensurable or inherently in conflict with each other? New research demonstrates that some of the most highly esteemed philosophers in Western Europe – including idealist philosophers Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Immanuel Kant, and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel – were significantly influenced by the Chinese philosophical tradition. Moreover, despite the widespread assumption that Ruism (Confucianism) is a conservative worldview, the influence of Neo- Confucianism (which dates from the twelfth century and incorporates Daoist and Mahayana Buddhist perspectives) has contributed to the ideas of progressive liberals and Marxist revolutionary leaders in both China and the West.

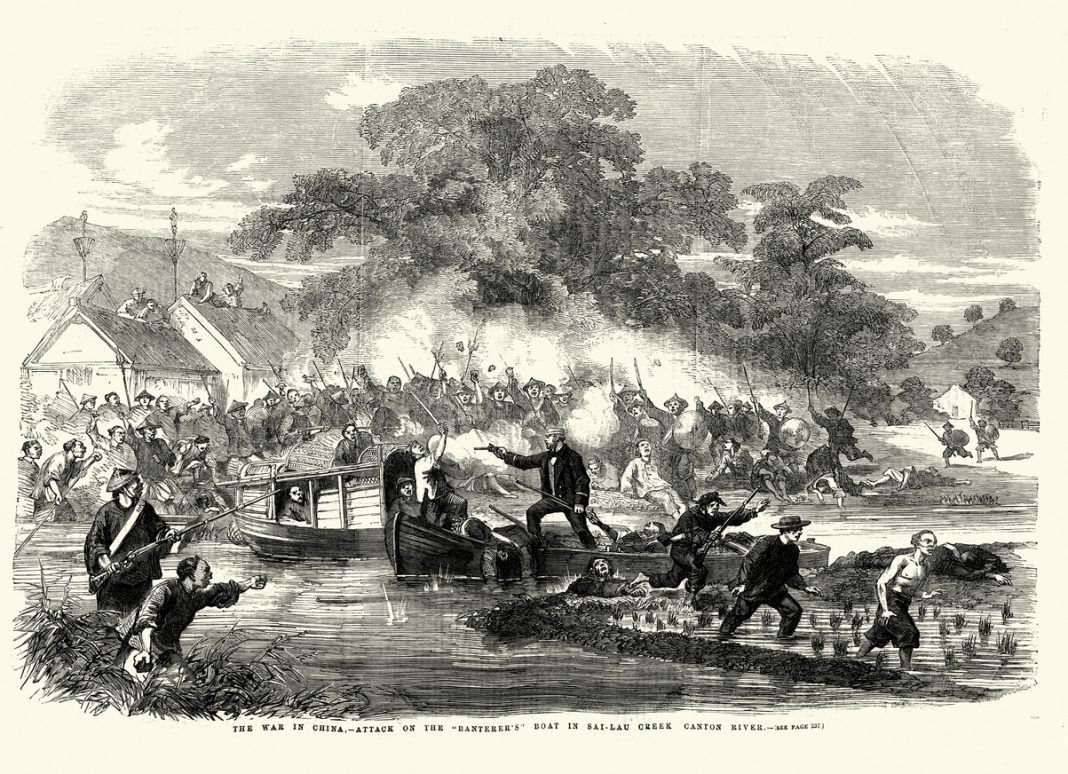

How is this possible? The key lies in Christianity, from which Enlightenment philosophers sought to liberate themselves. European voyages of discovery and conquest were accompanied and legitimized by the expansion of the Christian military enterprise to Asia and the Americas. In China, this resulted in the Opium Wars, won by superior Western technology. Yet the influence between East and West was not unidirectional. When Mateo Ricci arrived in China in 1582, Europeans were impressed with Chinese learning, inventions (e.g., astronomy, gunpowder, paper, and woodblock printing), and silks, arts, and furnishings (chinoiserie). Ricci adopted Chinese dress and rites and advised the emperor on calendrical science. He saw parallels between Catholicism and Confucianism, convincing him that Christianity and Ruism were fundamentally compatible.

After learning from a French missionary that Leibniz’s own binary mathematical system was presaged by the yin-yang schema (pictured) of the ancient Chinese Book of Changes (circa 750-1000 BCE), Leibniz maintained correspondence with such missionaries to learn more about Chinese philosophy. Their information included, without distinction, Neo-Confucian ideas as well as the classical Ruism of Kongzi (whom they christened ‘Confucius’). These ideas confirmed Leibniz’s view of the Universe as an organic whole governed by a pre-established harmony. The Leibniz-Wolff School affected the views of Kant and Hegel, as reflected in the distinction between noumenon and phenomenon and the notion of the dialectic. (1)

This influence has reverberated through multiple streams of Eastern and Western philosophy since then. The major conduits have been Marxist, neo-Kantian, and neo-Hegelian philosophies. What are the implications of this?

First, Neo-Confucianism has proven to be of enduring significance internationally. Its persistence as part of Chinese tradition and its reflection in Marxist philosophy contributed significantly to the Chinese revolution. The revolutionary thought of Mao Zedong and Liu Shaoqi, the Chinese Communist Party’s most powerful theorists through the 1970s, incorporated Neo-Confucian ideas regarding epistemology (how we know what we know), the relationship between theory and practice, and the emphasis on the mind-and-heart as the locus of consciousness, all of which informed their Sinification of Marxism and helped to ensure the success of the Chinese revolutionary movement.(2)

Such indirect Neo-Confucian influence is also reflected in the evolution of Latin American liberation theology and its variants in other countries, (3) as well as in the role of Wang Yangming’s (1472-1538) Neo-Confucianism in animating the Japanese Meiji Restoration (1868). The overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate and the ensuing industrializing revolution from above rapidly transformed Japan from an internationally isolated feudal society into a leading industrial power by the 1920s. (4)

These direct and indirect Neo-Confucian influences explain some striking, otherwise inexplicable, similarities between Chinese and other progressive thinkers and activists in Western Europe and Japan. The Italian union leader Antonio Gramsci (1891- 1937), born just two years before Mao, was arrested by the Mussolini government shortly after his election as an Italian Communist Party deputy to parliament in 1926. He shared with Mao and Liu – of whose existence he was unaware – their emphasis on the importance of consciousness, the unity of theory and practice, and the need for cultural transformation in a socialist revolution. This was the product of the convergence between China’s Neo- Confucian heritage and the Neo- Hegelianism and Marxism that influenced Gramsci’s Italian mentors. (5)

Acknowledging intellectual legacy

In short, Neo-Confucianism represents a shared East Asian and European philosophical legacy. With its valuable resources for understanding and promoting socio-economic, cultural, and political change, it merits more attention in current philosophical debates in the continuing struggle between democratizing and authoritarian forces not only within, but well beyond, China. Moreover, recognition of this global intellectual legacy could generate greater mutual understanding among Eastern and Western scholars and policymakers.

References

- Germaine A. Hoston, “Neo-Confucianism and German Idealism,” Journal of the History of Ideas 85.2 (April 2024): 257-287, https://doi.org/10.1353/jhi.2024.a926149.

- Germaine A. Hoston, “Revolutionary Confucianism? Neo-Confucian Idealism and Modern Chinese Revolutionary Thought,” Political Research Quarterly, 77.2 (2024): 607-619, https://doi.org/10.1177/10659129241228489

- Germaine A. Hoston, “A Neo-Confucian ‘Theology of Liberation’? Humanism and Ethics in Levinas, Liberation Theology, and Wang Yangming,” Harvard Theology Review 118.1 (January 2025): 85-109, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0017816025000069

- Germaine A. Hoston, “Civil Society, the Public Sphere, and Modernity in Japanese Political Thought,” Journal of International Political Theory, published online May 15, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1177/17550882251332521

- Germaine A. Hoston, “Consciousness, Will, and Cultural Revolution in Gramsci and Mao,” Philosophy and Social Criticism, published online on January 4, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1177/01914537241308124