Worldwide, approximately 12% of youth aged 5-24 years have at least one mental health diagnosis, how will the deprescribing of psychotropic medication in children and youth make a change?

Worldwide, approximately 12% of youth aged 5-24 years have at least one mental health diagnosis, but this number varies by age, sex, geographical region, and other factors.(1) The rates in the U.S. are estimated to be about 20% with increasing rates in younger children.(2) When considering all forms of burden to the child and family, such as medical burden, functional impairments, and decreased productivity of those with mental health disorders and those who care for them, the estimated cost in the U.S is approximately $250 billion per year.(2, 3) This constitutes a major health concern. Interventions are needed to ensure that these children receive optimal care that addresses the complexity of factors that have been associated with the development of mental health issues in childhood.

This document is a follow-up to the article entitled, “Rational Use of Psychotropic Medications in Youth,” which appear on this site in September 2025. Please see that paper for additional information.

A team of researchers and clinician scientists in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Louisville School of Medicine worked with the Kentucky Department of Medicaid Services, which provides health insurance to families with low incomes, to promote improved care quality around the issue of psychotropic medication use for children and youth, especially the most vulnerable such as those living in poverty and those in foster care. Approximately half of the children in Kentucky are insured through Medicaid. Through that work, we developed a website and resources to support this quality improvement initiative to promote the judicial use of psychotropic medications. The concept of deprescribing was described in the previously published article from September 2025.

The website is called, “Kentucky SafeMed”. Although the project has ended and no new materials are being produced, the existing resources are available for use or modification. The website is broken down with the following subheadings (click on hyperlink).

- Overview

- For Providers

- For Parents/Caregivers

- For Teens

- For Department of Community Based Services’ (DCBS) Social Workers (foster care system)

- Materials and Resources

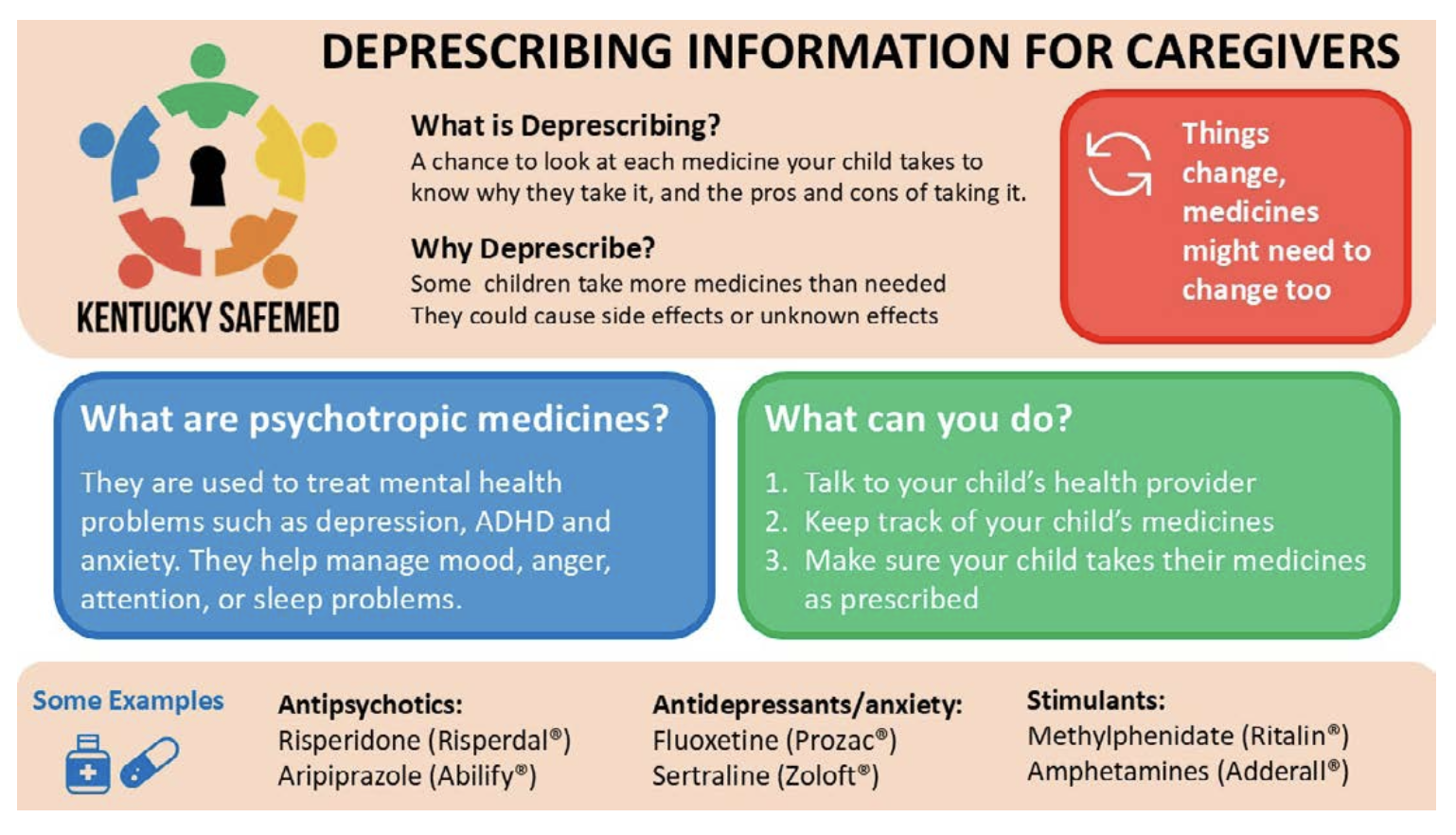

The following infographics are samples of the resources available for use. The first one was designed to help caregivers (parents and/or guardians) to understand the process of deprescribing. Care was taken to make the materials informative yet written in plain language to facilitate understanding.

The following infographics are samples of the resources available for use. The first one was designed to help caregivers (parents and/or guardians) to understand the process of deprescribing. Care was taken to make the materials informative yet written in plain language to facilitate understanding.

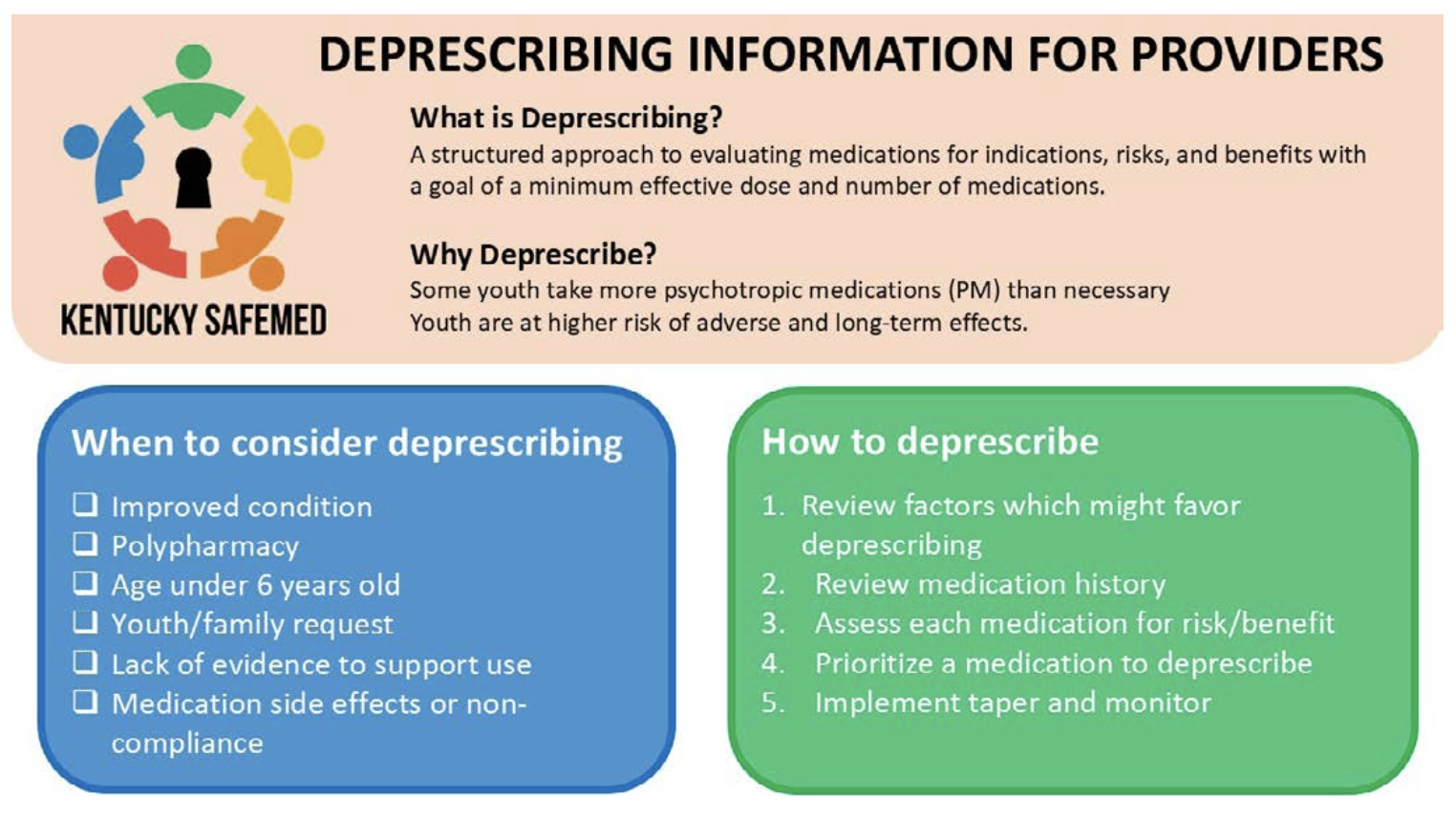

The second infographic was designed for healthcare professionals. Medication providers may be trained in child and adolescent psychiatry, but often primary care pediatricians, advanced practice nurses, and other healthcare professionals may be involved in prescribing or renewing medications. Through our quality improvement work, we found that many providers would like more information related to psychotropic medications, especially antipsychotics.(4) Deprescribing may be a new term to some. These materials, as well as other resources on the site, provide guidance to support clinical decision-making.

Lastly, the final graphic provides information so that youth can make informed decisions about their own care. These terms and processes may be unfamiliar to youth. These materials were designed to support youth in advocating for themselves.

The information here provides some general guidance, but much more research is needed to provide evidence for the specific steps in the process.(5-7) Recent systematic reviews have examined deprescribing for specific groups and medication classes, but much more work is needed.(5-7) Below are some examples of areas where there are gaps in the literature:

-

- Identifying populations or sub-populations that may benefit more from deprescribing specific classes of medications.(6)

- Identifying the additional interventions that can best support the youth during the deprescribing process to ensure that relapses are kept to a minimum.(5, 6)

- Identifying youth, family, and provider barriers to medication reduction or discontinuation.(5, 6)

- Identifying facilitators of shared decision making to ensure that deprescribing is meeting the needs of the patient and their caregivers.(5)

- Identifying factors associated with titration duration and timing, polypharmacy, appropriate frequency and duration of follow-up.(5, 6)

- Identifying factors associated with barriers and facilitators of quality of life for both youth and caregivers.(5)

- Identifying rates of recurrent behavior problems, re-prescribing, adverse effects, and outcomes (decreased dosage vs discontinuation).(5)

While not exhaustive, these examples indicate that a lot of work is needed to ensure that deprescribing is done based on evidence. The evidence must include a broad range of studies including pharmacological and pharmacokinetic studies as well as studies of psychosocial environments including family support systems and community resources. All of this work must be done within a trauma-informed framework and a health equity lens.

Additional readings related to childhood mental health and/or psychotropic medication use can be found at the end of this document.(2, 4, 8-17)