Loren E. Babcock, Professor in the School of Earth Sciences at The Ohio State University, introduces research on Cladoselache, a puzzling ancient shark-like fish

The Devonian Period, ~420 to 359 million years ago, is known in colloquial terms as the “Age of Fishes.” During this time, early cartilaginous and bony fishes experienced substantial diversification and adaptation to varied habitats. One characteristic and commonly illustrated Devonian fish is the shark-like Cladoselache (pronounced “klade-oh-sell-æ-key”), known from numerous specimens, some virtually complete, found in Late Devonian-age (~370 million-year-old) iron-carbonate concretions collected in and around Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. (1-4)

Although these specimens illustrate considerable anatomical details, and perhaps partly because of that, this fish poses a number of perplexing questions bearing on the evolution and paleoecology of Paleozoic cartilaginous fishes.

An introduction to Cladoselache, an ancient shark-like fish

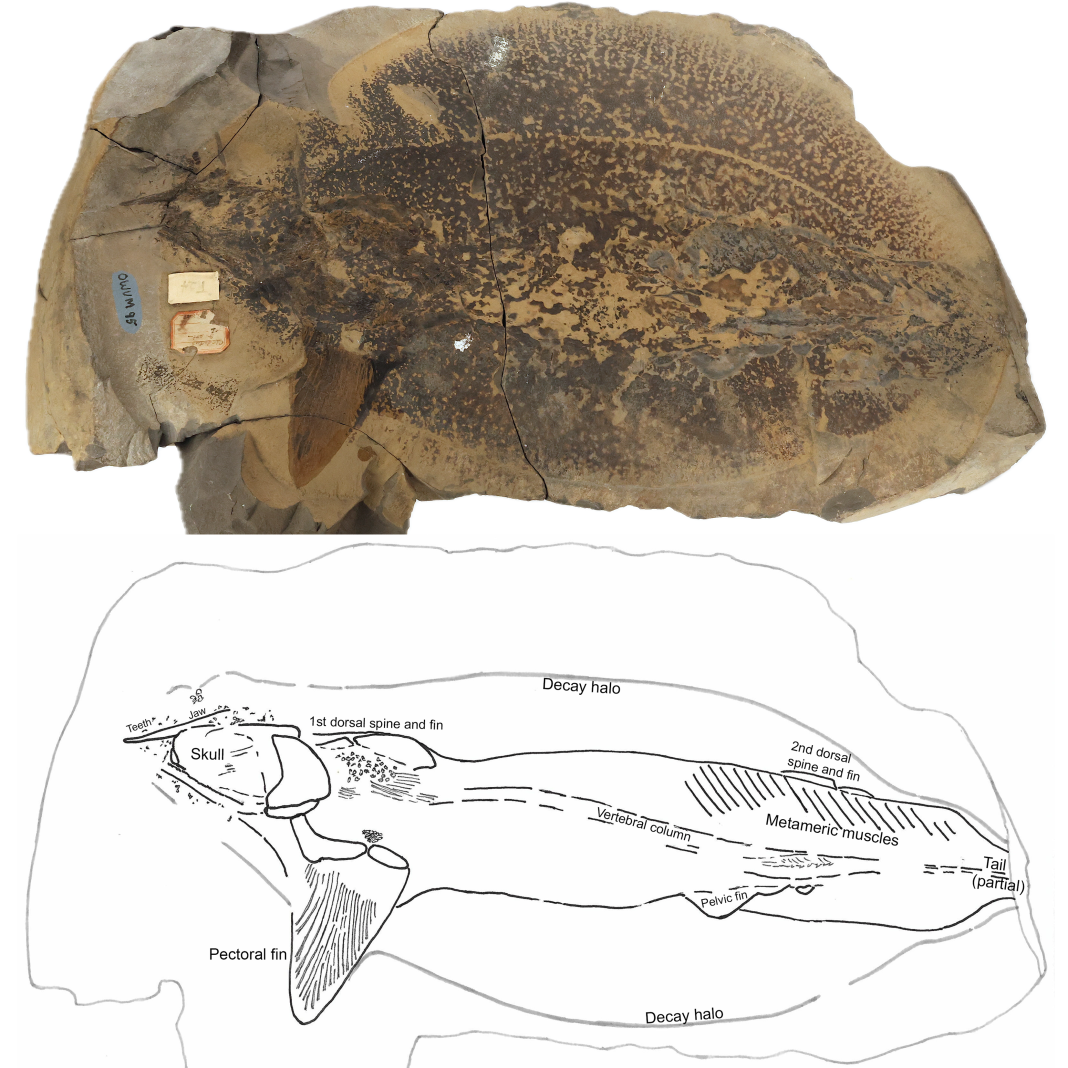

Cladoselache specimens are almost always found in elongate, rounded, iron-carbonate concretions that occur in black shales of the Cleveland Shale Member of the Ohio Shale (Figure 1). These are among the best-known examples of exceptional fossil preservation: both hard parts, such as biomineralized teeth, and non-biomineralized parts, such as cartilage and muscle, have been fossilized. The black shales are thought to represent low-oxygen, organic-rich muds where acidic, reducing pH conditions existed at the time of deposition. (3) Carbonate minerals, however, require moderately high pH (alkaline) conditions to form, so the presence of fish-bearing concretions in black shale seems paradoxical.

It was long thought that concretions took a long time to form. This was a corollary to the largely erroneous idea that fossilization processes in general require thousands to millions of years. Experimental work and comparison with fossil-bearing concretions have demonstrated that these mineral masses begin to form within days of an organism’s death. (5)

Decay-related micro-organisms, both fungi and bacteria, quickly form a biofilm or “decay halo” around a dead organism, and then mediate mineral precipitation within a micro-environment that differs chemically from that of surrounding sediments. This leads to a semi-lithified proto-concretion and later, a fully lithified concretion. If this process is initiated quickly enough, readily decomposable body parts will be encased and preserved as fossil. All this happens long before the sediment turns to rock, and it appears that such decay halos promoted localized concretionary growth around organic matter, even if reducing conditions were present in surrounding muds.

Cladoselache, the subject of much research

As an early cartilaginous fish having a shared evolutionary relationship with sharks and other chondrichthyans, Cladoselache has been the subject of numerous studies. (6) For more than a century, it was considered a shark (2-4) because of its cartilaginous skeleton, its lack of ribs, and the presence of dermal denticles, supports for gill slits, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. It also has a body form resembling a mackerel shark and teeth that broadly resemble those of some modern sharks. The teeth were replaced during life, but at a slow rate.

Unlike true sharks, Cladoselache lacks a loose jaw suspension and lacks enameloid teeth. It also has a mouth at the front of the skull, rather than on the ventral side, as do most present-day sharks. Recently, this animal has been classified in the same group as chimaeras, a sister group to true sharks (7).

Exceptional preservation of this early shark-like cartilaginous fish has revealed important anatomical details, but vexing questions remain. One unresolved issue involves their reproduction. Chondrichthyans, including sharks, have internal fertilization. Males usually have claspers, which are used for sperm transfer, but claspers have never been found in Cladoselache. (6,8) The question is: Why not? Did Cladoselache differ from related fishes and have external fertilization?

This would be difficult to test from fossils, but it is considered unlikely. Could it be that all nearly complete Cladoselache fossils we know of are females? If so, this leads to other questions. Some present-day chondrichthyan species are parthenogenic, meaning they can reproduce without a genetic contribution from males. Were Cladoselache species pathenogenic? Again, this is difficult to test from fossils.

The answer to this puzzle may be related to the life habits of the fish, and the concretions containing the fossils could hold the clues needed to unravel the chain of events leading to the preferential preservation of females as fossils.

One peculiar aspect of the occurrence of Cladoselache in Cleveland Shale concretions is that the fossils are concentrated in one relatively small area: Cuyahoga County, Ohio, whereas similar concretions devoid of these fossils occur over a much greater geographic area. The chondrichthyan-bearing concretions formed near the margin of the Appalachian Basin, which formed part of a vast inland sea during the Late Devonian. Ancestral North America, called Laurentia, was in a different location then; it lay astride the equator and was rotated clockwise about 90º from its present orientation. Present-day northern Ohio was located ~23º S latitude, in the tropics, and most likely in the path of tropical storms whose effects would have been most significant near the basin margin.

Like many of their modern, distant cousins among the true sharks, Cladoselache females probably selected shallow, protected areas such as coastal inlets and estuaries for giving birth to their pups. Storm conditions during birthing season, thus, would have mostly impacted female adults. Fishes that were caught up in storm conditions would have had a high chance of fossilization if coastal waters contained enough calcium ions for micro-organisms to rapidly initiate the process of concretion formation.

Calcifying green and brown algae, which were almost certainly abundant in shallow, tropical, coastal waters during the Devonian Period, were probably instrumental in maintaining sufficient calcium concentrations in the seawater.

Acknowledgements. JB Krygier, LJ Anderson, DM Jones, and C Querin led efforts to preserve and promote the importance of Cladoselache specimens in the 19th-century geological collection of Ohio Wesleyan University. Work was funded by the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Save America’s Treasures Program Grant/Cooperative Agreement (P25AP01904-00) and a grant from the Battelle Engineering, Technology, and Human Affairs Endowment Fund (GF600375).

References

- Newberry JS. The Paleozoic Fishes of North America. U.S. Geol.Surv. Monogr., 1889; 16:1–340.

- Dean B. Studies on fossil fishes (sharks, chimaeroids and arthrodires). Mem. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist., 1909; Pt. V, 9:211–287.

- Williams ME. Feeding behavior in Cleveland Shale fishes. In: Boucot AJ, Evolutionary Paleobiology of Behavior and Coevolution. Elsevier, 1990; 273–387.

- Zangerl R. Handbook of Paleoichthyology; Chondrichthyes I, Paleozoic Elasmobranchii. Gustav Fischer Verlag, 1981.

- Babcock LE. Marine arthropod Fossil-Lagerstätten. Jour. Paleontol. 99(3):506–523. https://doi.org/10.1017/jpa.2025.2

- Janvier P. Early Vertebrates. Clarendon Press, 1996.

- Coates MI, Gess RW., Finarelli JA, Criswell KE, Tietjen K. A symmoriiform chondrichthyan braincase and the origin of chimaeroid fishes. Nature, 2017; 541:208–211. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20806

- Maisey J. Discovering Fossil Fishes. Henry Holt & Co., 1996.