Professor David Ussery and Dr. Ake Vastermark, bioinformatics and microbial taxonomy experts at Oklahoma State University, introduce the challenges of defining bacterial species in an era of rapidly expanding genomic data. Their article highlights how modern genome-based tools can bring clarity to this evolving field

How does one define a bacterial species? This is not as easy as it might sound – biology is messy and the species boundaries are fuzzy. Bacteria divide asexually and can live almost anywhere, and their genomes contain many mobile elements, viruses, and plasmids. Having said that, it is important to know ‘who is there’ in terms of the microbial composition. And knowing ‘who is there’ implies knowing the names (some sort of unique identifiers).

Historical foundations of bacterial naming

Since the time of Aristotle, biologists have been naming organisms. Carl Linnaeus started to systematically give binomial names (Genus species) to all known plants and animals in 1735. Although the first bacteria were observed about 60 years before that (Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in 1676), it was not until 1823 that the first bacterium was given a Genus name still recognized today (Serratia), and the type of strain is currently known as Serratia marcescens ATCC 13880T CDC 813-60T NCTC 10211T. The first standardized bacteriological code was introduced in 1947, based mainly on morphological and metabolic properties observed by growing monocultures. Carl Woese et al. introduced using sequence-based methods (16S rRNA) in 1977 and discovered that ‘bacteria’ consisted of two very different large groups of organisms, now called Archaea and Bacteria (1). 16S rRNA has become the ‘gold standard’ for identification, although this method is based on a single gene, which can be present in multiple copies in many genomes, and can also be horizontally transferred to other organisms.

Now in the ‘genomics age’, the best unique identifier for an organism is the full genomic sequence for that organism (DNA or RNA). However, it is important to keep track and preserve the historical work of naming and classification of bacteria based on physiological properties. The number of names of bacterial species has exploded in recent years, with the number of validly published bacterial species going from around 2500 names in 1981 to now more than ten times that – more than 26,000 species in 2025 (2). In contrast, the most recent version of the Genome Taxonomy Database (3) contains about five times as many species – more than 136,000 named species. This explosion of genomic information and genome- based methods for naming bacterial species has created several problems, as discussed below.

Emerging taxonomic Challenges

- Lack of synonyms. Proposing new names is sometimes necessary, as old names might be reflective of taxonomic groups now shown to be different. However, the best solution to this is to include pointers to the former names, so that older microbiologists can still find information about organisms based on the older names. For example, we have compared more than 600 Clostridium difficile genomes (4); one day in 2013, this name suddenly disappeared from the databases, as the name was changed to Peptoclostridium difficile, and a few years later, in 2016, the name was changed again to Clostridioides difficile, so at least now a medical doctor looking for ‘C. difficile’ could find something in the database.

- The scale of name changes is very large – the most recent release of GTDB shows that more than 80% of the names of bacterial species have been changed. This means that microbiomes – all the names of the organisms in an environmental sample – can change rapidly with time, making the results more difficult to map with previous work, when the names might have been different.

- Many of the new names for bacteria are based on ‘MAGs’ (metagenomic assembled genomes), which can be noisy and might contain mixtures of different organisms. There has been much published on this, and tools are being developed (5) to help deal with some of the genomic assembly/taxonomy problems.

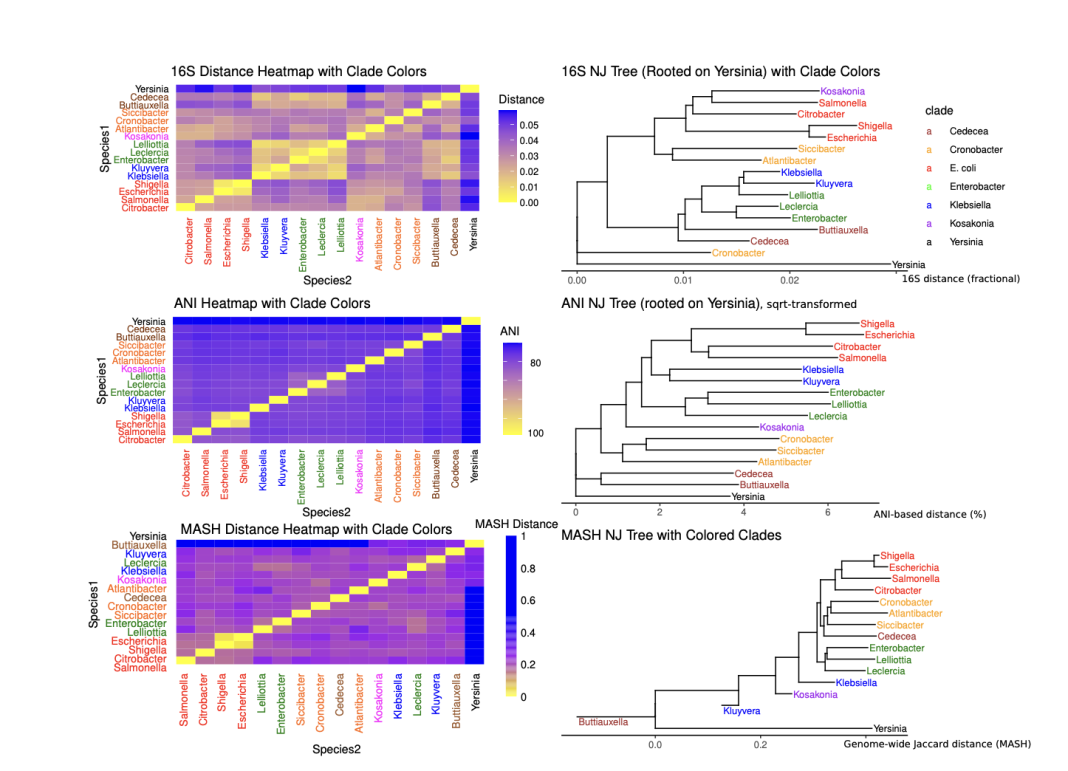

We are developing high-throughput methods for comparing millions of bacterial genomes, and anchoring their taxonomy based on known, validly published names of type strains. Traditional 16S rRNA classification has limitations, and with literally millions of full-length genome sequences available, alternative genome-based methods have been developed. One of the early methods was FastANI, which was the basis for the Genome Taxonomy Database (6), created in 2020. More recently, other alternatives, which are faster and can scale better, have been developed. MinHash (also known as MASH (7)) uses k-mer clustering (using the so-called “sketches” representation).

Clustering enterobacteriaceae type strains

As an example of these three methods, the figure shown here represents a set of three phylogenetic trees and heat maps, showing the distance between a set of 15 type strains, all from the Enterobacteriacae family (this includes the six clades shown in the figure). Notice that the MASH clustering gives a clear picture of the family, with one Yersinia genome as an outgroup. Serratia marcescens belongs to the Yersinia family and has a long history – as mentioned above, this is the first named bacterial genus that is still in use; it is easy to grow, naturally pigmented, and was used by the U.S. military (8) in the early 1950s to track bacterial aerosol spread in germ warfare tests. S. marcescens is an opportunistic pathogen that lives in moist environments and can grow on medical equipment, causing infections.

Scaling beyond phylogenetic trees

Phylogenetic trees become less useful as more genomes are added, and it is possible to scale heat maps to thousands of genomes, as we have shown previously (see, for example, figure 1 in Abram and Udaondo et al., 2000 (9)). Our group at OSU is developing high-throughput methods to compare millions of genomes and classify them into subspecies that preserve traditional experimental findings.

References:

- George E. Fox T, Linda J. Magrum, William E. Balcht, Ralph S. Wolfe, and Carl R. Woese, “Classification of methanogenic bacteria by 16S ribosomal RNA characterization”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, Vol. 74, No. 10, pp. 4537-4541, October 1977

- https://lpsn.dsmz.de

- https://gtdb.ecogenomic.org/

- Cabal, A., Jun, SR., Jenjaroenpun, P. et al. Genome-Based Comparison of Clostridioides difficile: Average Amino Acid Identity Analysis of Core Genomes. Microb Ecol 76, 801–813 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-018-1155-7

- Evans JT, Denef VJ.2020.To Dereplicate or Not To Dereplicate?. mSphere5: https://doi.org/10.1128/msphere.00971-19. https://doi.org/10.1128/msphere.00971-19

- Parks DH, Chuvochina M, Chaumeil PA, Rinke C, Mussig AJ, Hugenholtz P. A complete domain-to-species taxonomy for Bacteria and Archaea. Nat Biotechnol. 2020 Sep;38(9):1079-1086. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-020-0501-8. Epub 2020 Apr 27.

- Ondov, B.D., Treangen, T.J., Melsted, P. et al. Mash: fast genome and metagenome distance estimation using MinHash. Genome Biol 17, 132 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-0997-x

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/1950-us-released-bioweapon-san-francisco-180955819/

- Abram, K., Udaondo, Z., Bleker, C. et al. Mash-based analyses of Escherichia coligenomes reveal 14 distinct phylogroups. Commun Biol 4, 117 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01626-5