Lynette Abbott, Emerita Professor, The University of Western Australia School of Agriculture and Environment and UWA Institute of Agriculture, examines how the rhizosphere, a narrow collar of soil clinging to plant roots, is emerging as a key player in soil and plant health

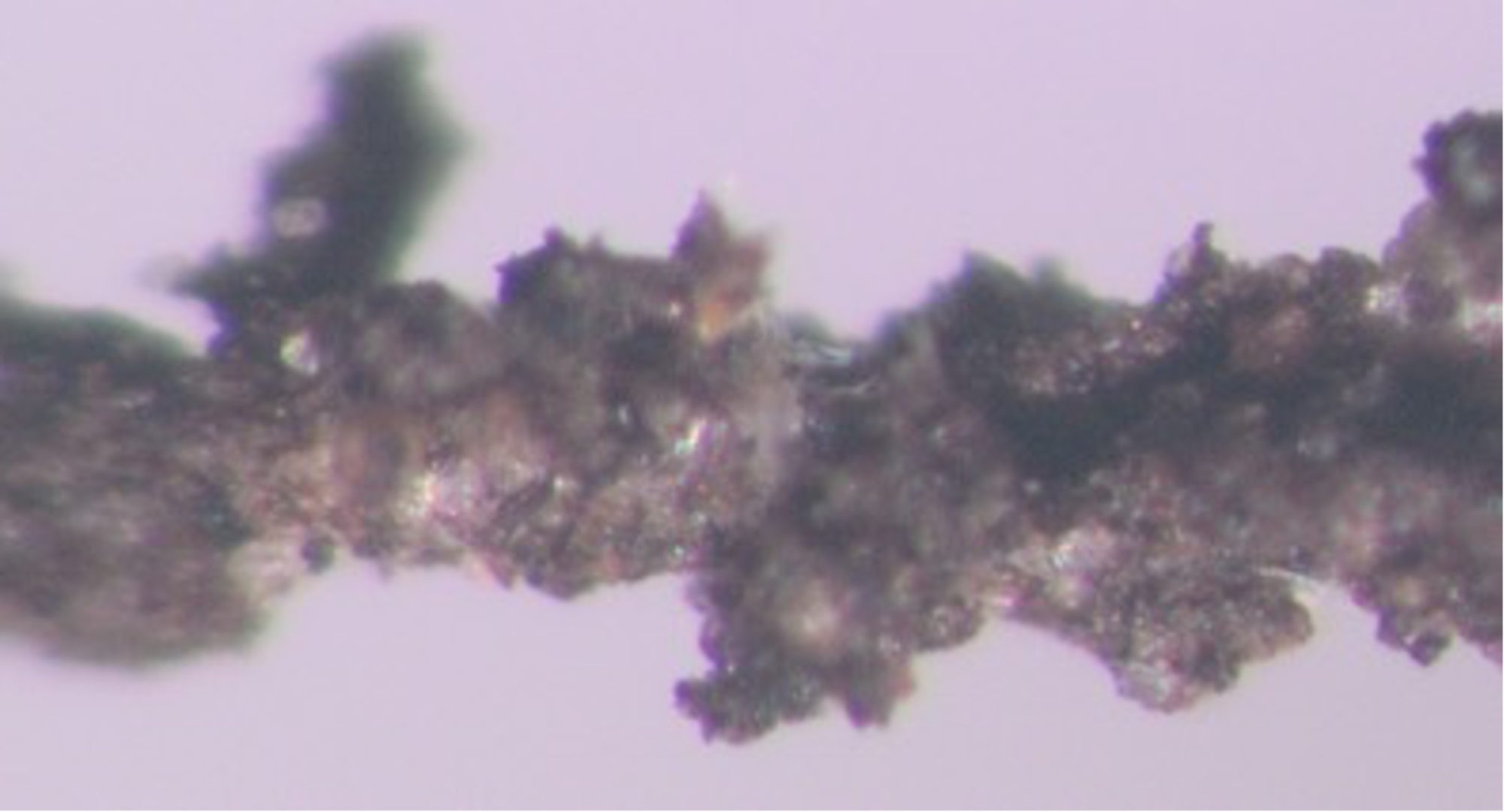

The rhizosphere is the area of soil that is in very close contact with roots (Photo 1). Roots profoundly influence microbial processes in this zone, and many of these processes are critical to soil health. As roots grow, they release a variety of exudates into soil, and many contain carbohydrates.

This stream of exudates provides a source of carbon and energy for soil microorganisms in close proximity to roots. Soil organisms multiply in this carbon-rich environment, creating a hotspot of microbial activity near roots. In turn, this enriched microbial community influences soil aggregation, roots and plant health.

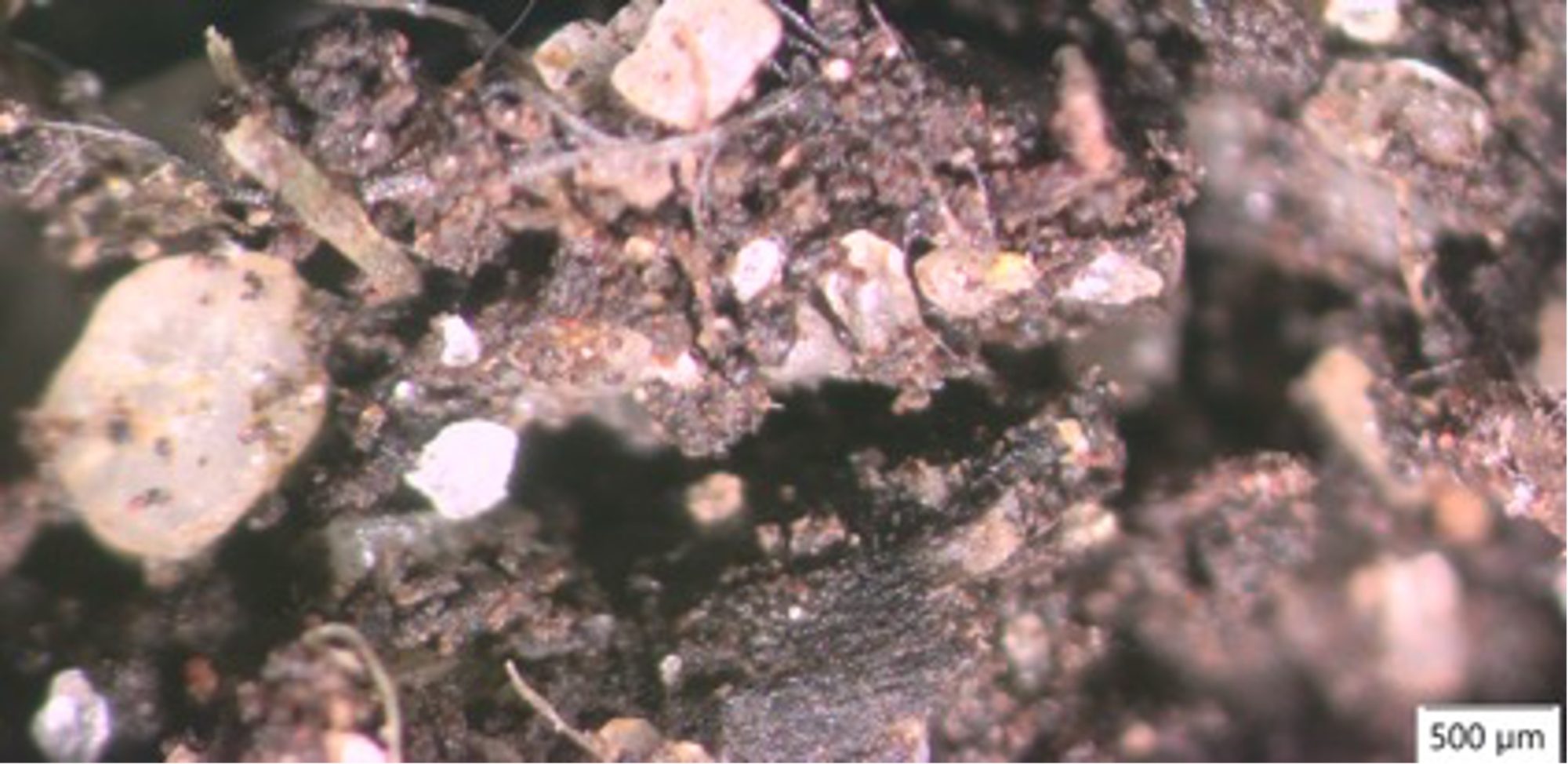

Root exudates help bind soil particles to roots (Photos 2, 3), which is further facilitated by fine root hairs, the multiplication of bacteria that release polysaccharide gums, and the proliferation of fungi that form networks of hyphae that connect the interior of roots to the surrounding soil. Root exudates also include molecules which facilitate the uptake of nutrients into roots, including iron, which is essential for some plant physiological processes. Exudation from roots can alter the pH of the rhizosphere and influence the availability of nutrients and activities of soil organisms. Interactions among microorganisms in the rhizosphere and roots can affect root architecture (such as root length, branching patterns, and thickness) as well as root health. The rhizosphere is a dynamic and complex environment. Diurnal fluxes of water into and out of roots directly influence microbial communities in the rhizosphere and the transfer of nutrients into roots.

The rhizosphere changes with age

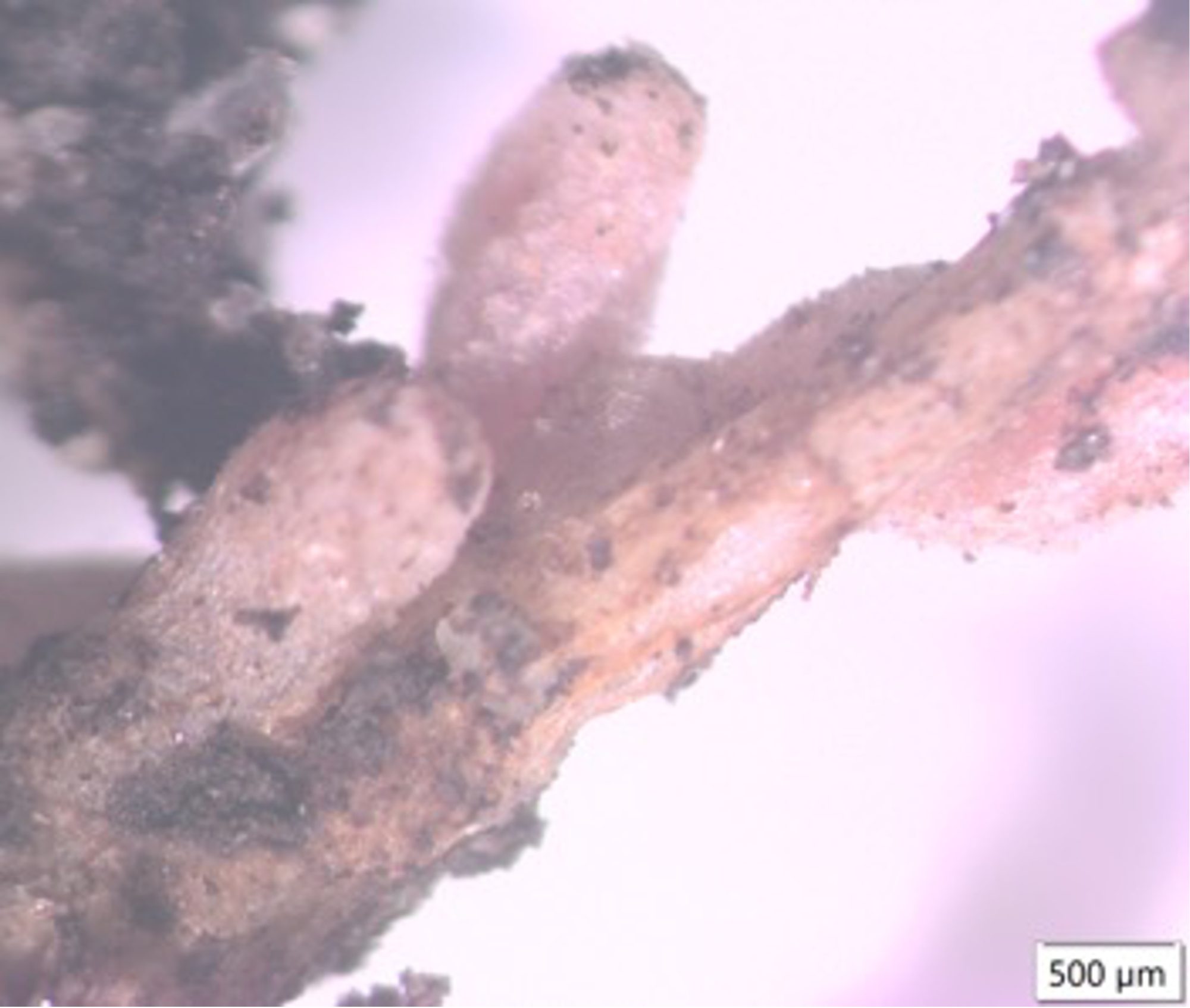

Exudation from roots changes as roots age. Older roots have different exudate patterns than younger roots, and older roots may die and decompose, further stimulating microbial responses in the rhizosphere. The formation of lateral roots or root damage can cause cell disruption and spill root contents into the rhizosphere (Photo 4), further contributing to a nutrient-rich rhizosphere habitat for soil organisms. These changes lead to a succession of microorganisms, increasing and decreasing activity over time and altering biochemical processes in the rhizosphere, which impact plant nutrition and plant health.

Symbiotic associations

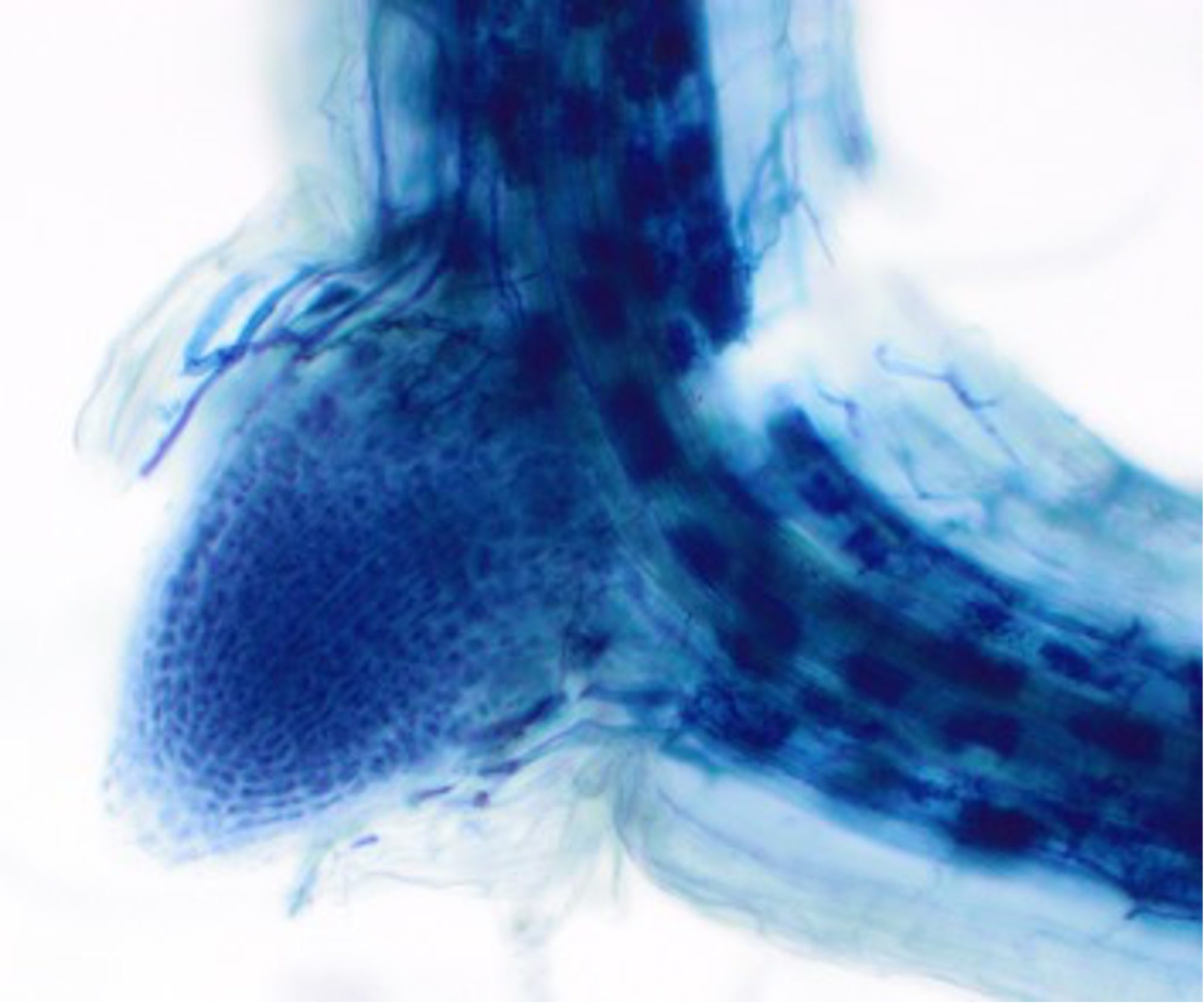

The rhizosphere is the location for the establishment of symbiotic associations between mycorrhizal fungi and roots of most plants, and between highly specialised bacterial symbioses formed with legumes that lead to biological nitrogen fixation (Photo 5).

Mycorrhizas give the fungi involved direct access to root carbohydrates inside roots, bypassing the root exudate pathway in the rhizosphere. These fungi enter roots from the rhizosphere and help plants access nutrients from soil, such as phosphorus, present in the rhizosphere as well as beyond the rhizosphere zone. Mycorrhizal fungi form networks of hyphae in rhizosphere soil, and can contribute to building the resilience of roots against soil-borne pathogens under some circumstances.

Legumes form symbiotic associations with root nodule bacteria (rhizobia). Nodules form on the roots of the host legume following highly specific molecular signalling that occurs between rhizobia and the surface of root hairs in the rhizosphere (Photos 4,5). Conditions in the rhizosphere can influence the success of nodulation and subsequent biological nitrogen fixation in the nodules. The bacteria multiply within the nodules and convert atmospheric nitrogen (N2) to a form of nitrogen which the plant can use. The biologically fixed nitrogen is released internally within the plant to supply its requirements, avoiding the requirement for access to nitrogen from soil.

The rhizosphere can be the origin of root disease. This may occur when plant pathogens proliferate around roots, or when high population levels of pathogens build up over time, such as following continuous cropping of plants that are susceptible to disease. On the other hand, soil organisms in the rhizosphere may build suppressive communities that deter the proliferation of root pathogens. The disease cycle can be broken when multiple different plant species are grown together to create a diverse habitat, which encourages a biodiversity hot-spot in the rhizosphere, reducing the opportunity for disease-causing organisms to proliferate and enter the roots. Use of some forms of soil amendments can change chemical or physical conditions in the rhizosphere that favour non-pathogenic microbial communities that deter pathogen access to roots.

The rhizosphere microbiome

Recent advances in molecular studies have opened new opportunities for investigating rhizosphere processes that may influence soil and plant health (see the open access article by Genesiska et al. 2025). This article addresses the roles of soil organisms in helping plants overcome adverse conditions. They consider knowledge of specialised metabolites in exudates derived from both plants and microorganisms in the rhizosphere. The quantities and kinds of these metabolites are influenced by stress conditions such as drought. However, there are many technical and analytical difficulties in investigating the roles of plant and microbial metabolites in rhizosphere soils. The authors foreshadow exciting future opportunities based on understanding the involvement of metabolites in communications between plants and microbiomes. Rhizosphere studies of metabolites from both plants and microorganisms are essential for exploring new management practices for overcoming constraints to soil and plant health.

Acknowledgements:

Our research on soil health is supported by the Soil Science Challenge Grants Program funded by the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (project 4-H4T24R2) and contributes towards the National Soil Strategy and the implementation of the National Soil Action Plan.

Our long-term soil carbon trial using different combinations of pasture species is funded by the Carbon Farming and Land Restoration Program of the Western Australian Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD).

References:

- Unveiling healthy soil: Why is soil biology key to soil health?

- Soil Structure: The foundation of healthy soil

- Soil health – A role for arbuscular mycorrhizas

- Soil health – Soil biodiversity is essential for building environmental resilience

- Genesiska, Falcao Salles, J. & Tiedge, K.J. Untangling the rhizosphere specialized metabolome. Phytochem Rev 24, 2527–2537 (2025).