Recently, Bayer, the producer of the herbicide RoundupTM, announced that the controversial herbicide glyphosate would be phased out of consumer RoundupTM products and replaced by other active ingredients, including the herbicide diquat

While the U.S. has resisted calls to regulate diquat, it is banned in the UK, EU, China and other countries because of concerns regarding its environmental persistence and toxicity.

An estimated 40,000 to 350,000 chemicals are on the global market, with hundreds of new chemicals introduced annually. In many regions, including the European Union (EU), the United States (U.S.), and much of Asia and South America, new chemicals can enter the market with limited safety information. There are numerous examples of chemicals for which post-market evidence of safety issues arise as the product is used and as the toxicology research community studies the product in more depth. If these safety issues are sufficient to cause considerable consumer concern and/or prompt regulatory action to restrict or ban the particular product, manufacturers typically replace the chemical of concern with a different chemical for which there are currently no regulations. To avoid a complex and expensive redesign of products or manufacturing processes that the chemicals are used in, manufacturers often substitute the hazardous chemical with structurally similar chemicals. However, structurally similar chemicals often have similar toxicological effects. Alternatively, manufacturers may switch to a completely different family of chemicals for which there is limited data or a new material with similar chemical properties, including toxicity, for which there are no current regulations in at least some regions with sizable markets. This switching from a known hazardous substance to a not-yet-known hazardous substance or unregulated hazardous chemical is referred to as “regrettable substitution”.

One example of this chemical “whack-a-mole” is the switch from bisphenol A (BPA) to bisphenol S (BPS) or bisphenol F (BPF) in consumer plastic products, such as plastic bottles. For many years, BPA has been linked to various adverse health outcomes, such as reduced semen quality and other reproductive and immune system effects. Due to growing consumer pressure and increased regulation, companies voluntarily phased out BPA, marketing their products as “BPA-free”. However, the BPA in products is often switched to another, structurally similar bisphenol such as BPS or BPF, and there is growing evidence that BPS and BPF are as or more toxic than BPA.

The development of major synthetic classes of pesticides, particularly insecticides, began in the 1930s when Paul Mueller found that dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) acted as a poison on flies, mosquitoes, and other insects. DDT was commercialized in 1942 and used extensively and successfully around the world to control typhus epidemics and malaria. During this time, other chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticides were also developed, including lindane, mirex, aldrin, dieldrin, heptachlor, endrin, and toxaphene. However, by the 1970s, many of these organochlorine insecticides were banned or phased out of production because of their environmental persistence and well-documented adverse effects on human health and ecosystems. Organochlorines were replaced by the organophosphate insecticides, which were equally efficacious in controlling insects but less persistent in the environment. However, the organophosphate insecticides were also subsequently discovered to pose significant risks to human health, and many are now highly restricted or banned.

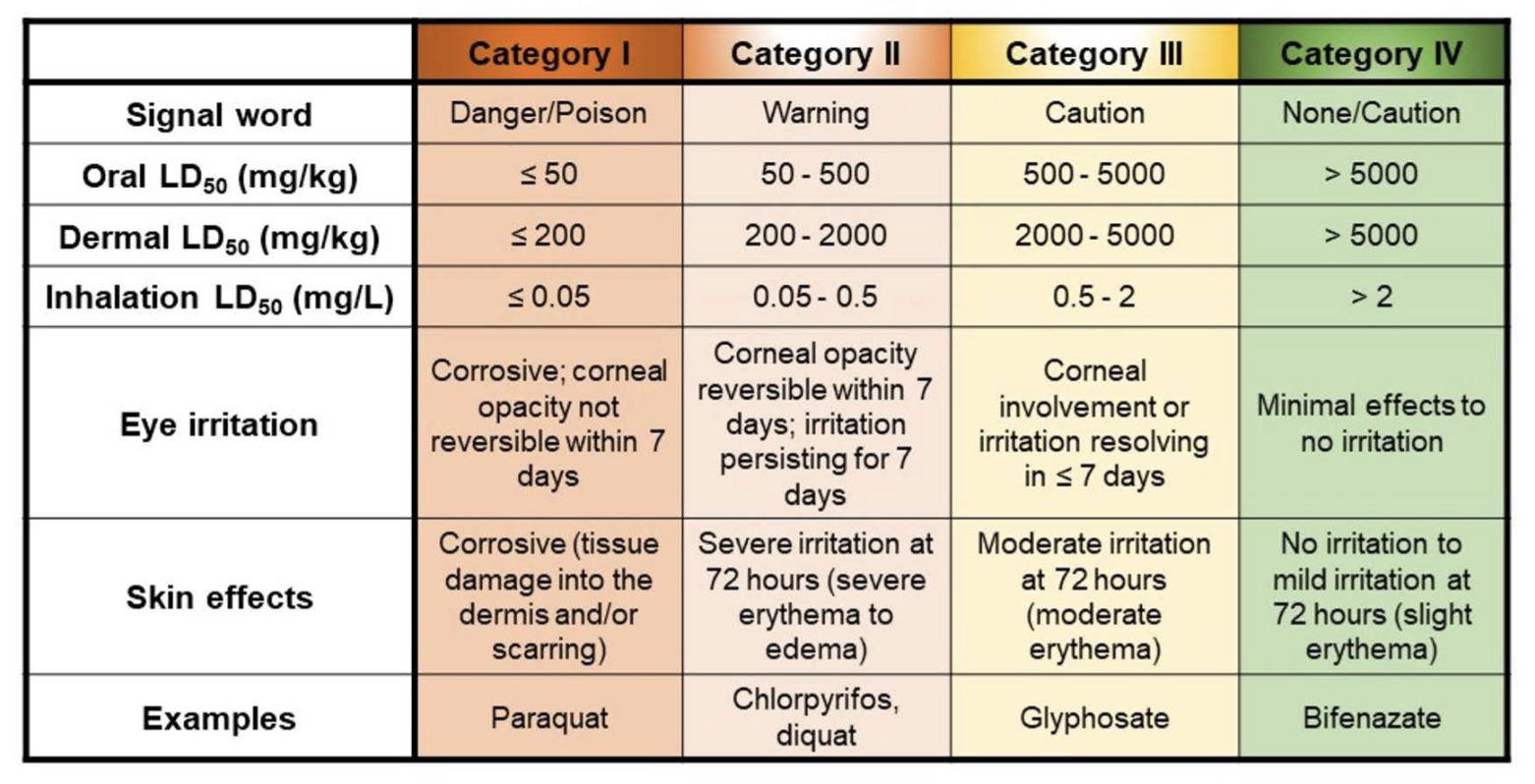

Despite the risks associated with pesticides, the worldwide agricultural use of pesticides has increased steadily between 1990 and 2025. Herbicides account for the largest share of the increased usage, with most of that growth attributed to glyphosate and its chemical analogs. Relative to most insecticides, herbicides, as a class, display relatively low acute toxicity, with one notable exception, which is paraquat and related analogs. However, a number of herbicides can cause dermal irritation and contact dermatitis, particularly in individuals prone to allergic reactions, while other compounds, particularly glyphosate and its analogs, have generated much debate regarding possible adverse effects associated with chronic or repeated exposures to low levels. Glyphosate, first marketed as RoundupTM in 1971 by Monsanto, is one of the most successful and widely used herbicides to date for weed control in commercial and residential settings. However, concerns regarding the adverse outcomes linked to chronic exposures of glyphosate began to surface in the 1990s and early 2000’s.

Bayer, which acquired Monsanto in 2018, has been the target of approximately 175,000 lawsuits claiming that glyphosate and its chemical analogs have caused cancer, specifically non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). Because of the controversy surrounding the potential adverse health effects of glyphosate, Bayer, the producer of the herbicide RoundupTM, announced that glyphosate would be phased out of consumer RoundupTM products and replaced by other active ingredients, including the herbicide diquat, which is an analog of paraquat. While the U.S. has resisted calls to regulate diquat, it is banned in the UK, EU, China and other countries because of concerns regarding its environmental persistence and its toxicity. Recent studies suggest that diquat may be more hazardous than glyphosate, causing damage to many internal organs such as the liver, kidneys, and GI tract. Such findings have triggered heated debates on whether replacing glyphosate with diquat is providing the public with a better and safer option, or whether this is yet another case of regrettable substitution in pesticide manufacturing.

The benefits of herbicides

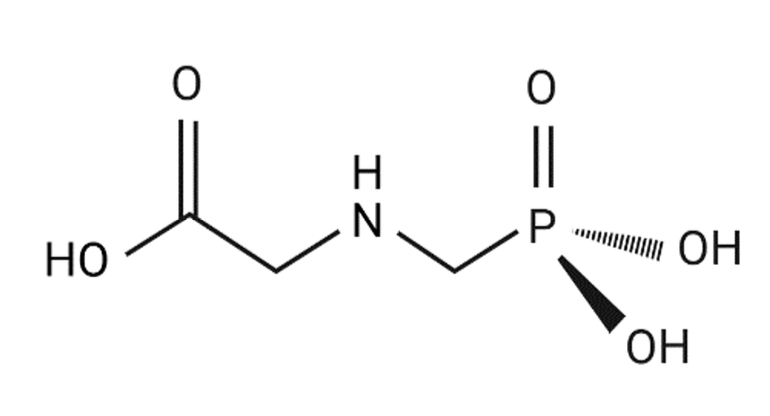

Glyphosate (N-(phosphonomethyl) glycine; Figure 1) is classified as an herbicide. As a class, herbicides are chemicals capable of killing or severely injuring plants. Herbicides have a significant role in maintaining crop health and yield by controlling the growth of unwanted plants that compete with crops for nutrients, water, and sunlight. They represent a very broad array of chemical classes and act on a large number of biochemical reactions that regulate metabolic functions and energy transfer in plant cells. For the past several decades, herbicides have represented the most rapidly growing sector of the agrochemical market, and these compounds now represent almost half of the pesticides used in the U.S., and more than one-third of those utilized worldwide. This can be ascribed in part to the shift in agriculture to monocultural practices, which has increased the risk of weed infestation, and to mechanization of agricultural practices to offset increased labor costs. It has been estimated that without herbicides, the U.S. would require an additional 70 million workers for weeding to prevent crop yield losses, while in China, about 1 billion person-days of labor would be required to adequately hand-weed the rice fields. Controlling weeds without herbicides represents one of the greatest obstacles, and thus one of the highest costs, to organic crop production. In addition to agricultural applications, herbicides are also widely utilized in the home and garden, at industrial and commercial facilities to control weeds, in forestry management to facilitate growth of new trees, and to clear roadsides and utilities’ rights of way.

Glyphosate is a non-selective, systemic herbicide used for post-emergent control of annual and perennial plants. It is highly effective in managing and controlling weed growth in agricultural production, forestry, and residential settings. Since its introduction under the trade name RoundupTM in the 1970s, numerous glyphosate-based herbicides (GBHs) have been developed by other manufacturers with formulations that contain glyphosate as the active ingredient combined with different inert ingredients. RoundupTM and other GBHs are the most widely used herbicides in the world, with particularly heavy use in more developed countries. In 2022, GBHs accounted for the largest share of herbicide sales in the EU.

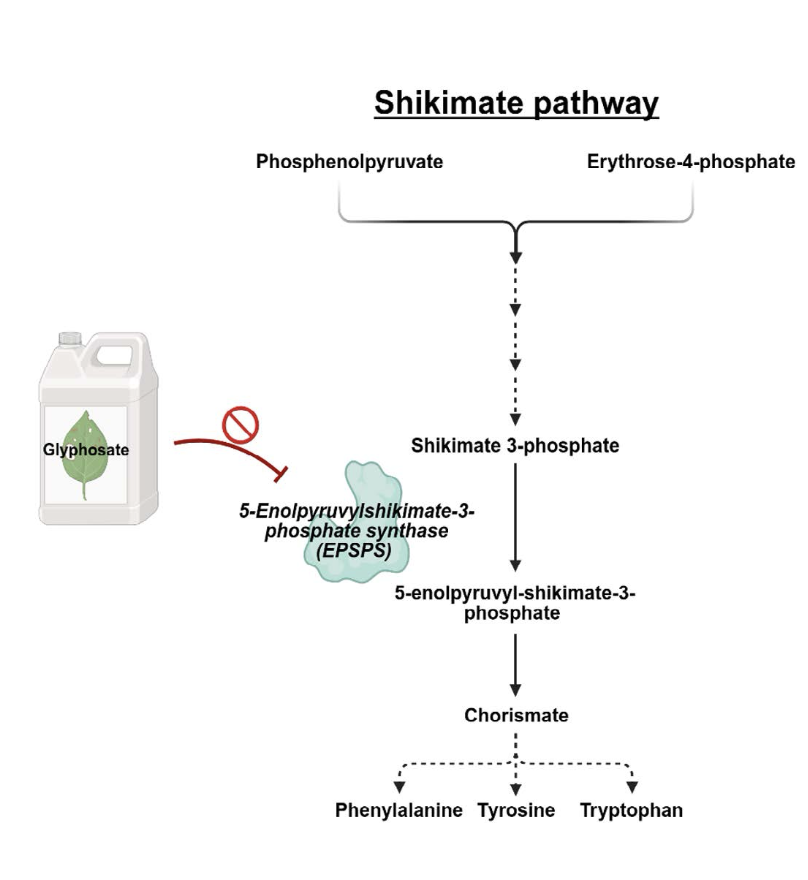

Glyphosate’s herbicidal action is mediated by its ability to block the shikimate pathway, a biosynthetic pathway that synthesizes the amino acids phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan (Figure 2). Glyphosate is a competitive inhibitor of the enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS), thus, binding of glyphosate to EPSPS blocks the binding of the enzyme’s endogenous substrate. Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan are required for plant growth; therefore, disruption of the shikimic acid pathway can effectively kill the plant. Since all plants rely on the shikimate pathway for growth, glyphosate formulations are not selective for weeds and can kill beneficial plants. To circumvent this problem, genetically engineered corn, soybeans, and grains that are resistant to glyphosate treatment were engineered, thereby reducing the potential for off-target effects on beneficial crops and simplifying application.

Glyphosate is generally considered safe because…

While there are several reported incidents of human death after intentional ingestion of concentrated glyphosate formulations, glyphosate is generally considered to be “safe” because the shikimate pathway is not present in humans and other animals, providing high selectivity to this compound. Scientific determination of high LD50 values (the dose that causes lethality in 50% of the exposed population) for glyphosate confirms its low acute toxicity in animals (see Table 1). For example, the oral LD50 in rats, mice, and goats is estimated to be 5,000 mg/kg, 10,000 mg/kg, and 3,530 mg/kg, respectively. In rabbits, the acute dermal LD50 exceeds 2,000 mg/kg. According to a 4-hour inhalation study, the inhalation LC50 in rats is higher than 4.43 mg/L.

While data regarding the fate of ingested glyphosate in humans is limited and confined to the oral exposure route, animal research indicates that ingested glyphosate is readily absorbed from the GI tract and probably the respiratory tract as well. Once glyphosate is absorbed, it is readily transported throughout the body but is rapidly eliminated in the urine with no appreciable accumulation in any specific organ or tissue. Less than 1% of glyphosate is eliminated as the metabolite aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA), indicating minimal metabolism of glyphosate. As a result, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has assigned glyphosate to Toxicity Category III (Table 1), which is the second to lowest hazard category. One significant caveat in interpreting the glyphosate toxicity literature is that these data were generated using the active ingredient, glyphosate. In the real-world, glyphosate is used as commercial formulations, which contain not only the active herbicidal glyphosate, but also other inert ingredients such as the surfactant polyethoxylated amine (POEA), for which there is evidence of toxicity to humans and animals.

In general, glyphosate is not thought to pose a significant risk to the ecosystem because it is readily degraded by soil microbes. Thus, its environmental persistence is considered to be low to moderate. However, its degradation in soil is influenced by many different factors, such as soil composition, temperature, and moisture. The scientific literature includes reports of a median half-life in soil ranging from 2 to 197 days, with a common field half-life of 47 days. Glyphosate also binds strongly to soil particles, which inactivates its herbicidal activity. However, repeated applications of glyphosate have been demonstrated to limit its biodegradation in the soil, leading to increased risk of groundwater contamination. Glyphosate is highly water-soluble with a half-life in water ranging from a few days to 91 days. But, in general, the concentrations of glyphosate in water samples have been shown to be below the levels of concern for humans or wildlife animals. However, due to its widespread use, this chemical may pose long- term environmental risks as well as potential adverse outcomes to human health as a result of chronic exposure to low concentrations of glyphosate.

However, there are concerns about chronic toxic effects of glyphosates

While the risk of acute toxicity is considered low for glyphosate and GBHs, over the past several decades, the health risks associated with chronic exposure to these herbicides have been debated by national and international regulatory agencies as well as the scientific community and consumer population. In 2015, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) categorized glyphosate as “possibly carcinogenic to humans” based on epidemiological studies that suggested positive correlations between the chemical and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). However, neither the joint evaluation by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the WHO on Pesticide Residues nor the EU have reached the same conclusion as the IARC. Additionally, in its latest interim decision for glyphosate’s registration review that was released in 2020, the U.S. EPA has also classified glyphosate as not likely to pose risks or concerns to human health.

This disagreement amongst regulatory agencies regarding the safety of glyphosate reflects the discrepant research findings regarding the carcinogenic risk of glyphosate. The Agricultural Health Study (AHS), a prospective cohort study published in 2005 that recruited 57,311 licensed pesticide applicators in Iowa and North Carolina between 1993 and 1997 with follow-up in 2001, found no statistically significant associations with glyphosate use and cancer incidence. In a follow-up study published in 2018 that extended the cancer incidence follow-up period to 2012 for North Carolina and 2013 for Iowa, the outcomes agreed with the previous findings of no associations between glyphosate exposure and increased cancer risk or development of lymphohematopoietic cancers (including NHL and multiple myeloma). However, the authors did report some evidence of an increased risk of acute myeloid leukemia for applicators, especially when comparing applicators with the highest glyphosate exposure group to those that had never used glyphosate. In contrast, several case-controlled studies and scientific reviews have reported evidence indicating that occupational exposures to these herbicides increased risks of developing certain types of cancers, specifically NHL. While meta-analyses of published studies investigating associations between glyphosate and NHL and/or other types of lymphohematopoietic cancer have yielded discrepant conclusions, all concluded that potential misclassification and selection bias of recruited participants for the cohort studies, as well as differences in the methodologies and statistical models used across studies, complicated interpretation of the available data.

In a review published in the scientific journal Environmental Health in 2020, the authors re-evaluated 13 toxicology and carcinogenicity studies of male and female rats and mice chronically exposed to glyphosate for 18 to 24 months that were cited in the IARC report and other regulatory agency reports. While there were no survival differences and no-to-mild weight loss observed in the high-dose glyphosate group in most studies, the authors suggested that there was clear evidence of increased incidence of various benign and malignant tumors in experimental rodent models, for example, malignant lymphoma in mice. Additionally, the landmark scientific study on glyphosate safety published in April 2000 in Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology that many regulators relied on for decades to justify the continued approval of glyphosate was recently retracted over serious ethical issues. In late November 2025, the publisher quietly retracted the study by Williams, Kroes and Munro that concluded glyphosate did not pose a health risk to humans at typical exposure levels, citing evidence that the article was ghostwritten by Monsanto employees and was based solely on unpublished studies from Monsanto. It also ignored multiple other long-term chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity studies that were available at the time the article was written.

Collectively, the more recent studies suggest that chronic exposure to glyphosate and GBHs increase risk of certain lymphohematopoietic cancers. This conclusion is supported by scientific evidence of a biologically plausible mechanism by which glyphosate could contribute to these cancers. Oxidative stress has been proposed as a key feature of carcinogenesis, including in the etiology of hematopoietic malignancies. Elevated biomarkers of oxidative stress, specifically 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) and 8-isoprostane, and malondialdehyde (MDA), were detected in the urine of farmers exposed to high levels of glyphosate. Additionally, a mechanistic study published in 2019 reported that glyphosate increased multiple myeloma in mice exposed for 72 weeks via a novel mechanism in which glyphosate upregulated expression of an enzyme that promotes mutations in B-cells, a type of immune cell involved in multiple myeloma.

While most toxicology studies have focused on glyphosate and cancer, there are also data indicating potential non-cancer health risks following chronic glyphosate exposures, including adverse effects on the nervous and reproductive systems, liver, and kidney. However, additional studies are needed in order to better understand the incidence, dose-response relationships and mechanisms underlying the multi- organ toxicity of glyphosate and GBH exposures.

Environmental impacts of glyphosate

GBHs can adversely impact not only humans but also ecosystems. Specifically, they pose serious threats to vital pollinators, such as honeybees, via multiple mechanisms. The decreased availability of floral resources, especially near agricultural areas where GBHs are applied, has significantly decreased food sources for honeybees and other commercially important pollinators. Monarch butterflies have been impacted by GBH-mediated die-off of milkweed plants, the sole food source for their caterpillars. Pollinators can also be harmed by direct contact with glyphosate via spray drift and absorption of residues in vegetation and water sources. Such exposures have been associated with damage to beneficial gut bacteria, which increases the honeybee’s susceptibility to pathogens, and reduced colony survival via disruption of thermoregulatory mechanisms. These observations have significant implications for not only the health of ecosystems but also the viability of numerous commercially important crops.

Is diquat a safer alternative to glyphosate?

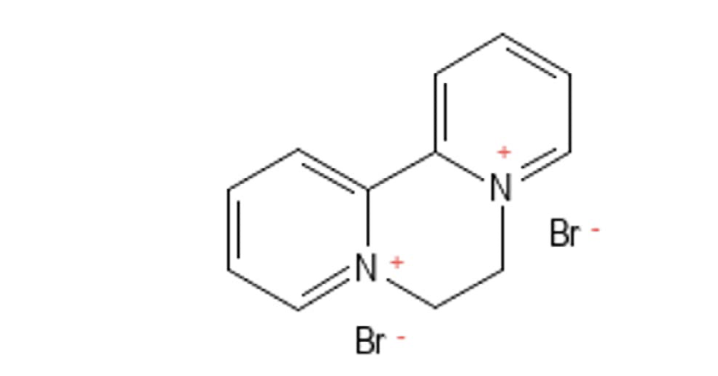

Because of the controversy associated with glyphosate and its analogs, Bayer is replacing glyphosate in consumer RoundupTM products with other herbicides, including diquat (Figure 3). Diquat is currently approved for use as an herbicide in a number of markets around the world, including the U.S. and many developing countries. There is significantly less safety data for diquat than there is for glyphosate; however, diquat is a structural analog of paraquat, a well-documented human toxicant. Moreover, the research that is available indicates that diquat causes multiorgan toxicity, is neurotoxic, and harms the gut microbiome. Additionally, diquat has been banned for use in the UK, EU, and China since 2018.

Diquat is a bipyridyl compound first synthesized in the 1950s. Like its structural analog, paraquat, diquat is a very effective, fast-acting, nonselective contact herbicide used to control broad-leaved weeds and grasses in plantations and fruit orchards, and for general weed control in hundreds of crops. Additionally, it is often used as a desiccant for crop harvesting, allowing farmers to dry seeds in a cost-efficient manner. Diquat works by penetrating plant leaves to disrupt Photosystem I, a protein complex involved in photosynthesis, resulting in the generation of superoxides. These are reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are unstable and highly reactive. Once generated, superoxides will cause oxidative damage to plant cell membranes, causing the plant to dry out. Under optimal conditions, e.g., warm temperatures and light, plants will begin wilting within hours and desiccate within days.

Acute toxicity of diquat

As it does in plants, diquat induces ROS in humans and experimental animals following acute poisoning, although the mechanism by which it generates ROS differs since humans and other animals do not express Photosystem I. The high levels of ROS generated by diquat cause oxidative stress that results in multiorgan toxicity. Humans who have ingested large amounts of diquat can develop acute kidney injury, largely caused by the disruption of cell membranes in the renal tubule. Diquat induces death of liver cells by disrupting mitochondrial function. In both the kidney and liver, diquat poisoning also induces inflammation. The gastrointestinal tract is also commonly harmed following diquat exposure. The induction of ROS damages intestinal epithelial cells in the gut, disrupting the intestinal barrier, which causes dysbiosis, an imbalance of gut microbiota characterized by an increase in harmful bacteria. Gut dysbiosis in turn induces an inflammatory response that can further exacerbate barrier damage in the gut, creating a cycle of inflammation and damage to the intestinal barrier. There is also evidence of neurological damage in humans who have intentionally ingested high concentrations of diquat. The type of adverse neurological effects observed in acutely intoxicated humans varied by case, but included intracerebral hemorrhage and abnormal neuroimaging findings. In contrast to acute paraquat toxicity, diquat does not accumulate in the lung, and no lung toxicity is seen upon acute intoxication with diquat.

Chronic toxicity of diquat

Unlike glyphosate, diquat is not considered carcinogenic. However, chronic exposure to diquat has been reported to damage multiple organs, likely via the generation of ROS. For example, chronic diquat exposure has been associated with the development of cataracts in both humans and experimental animal models, although this outcome varies depending on the dose and length of diquat exposure. Other experimental studies in rodents reported that a daily dose of diquat in drinking water for 21 days increased expression of biomarkers of inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract, specifically the stomach and jejunum.

Chronic exposure to paraquat is strongly associated with increased risk of Parkinson’s disease in humans, and it induces Parkinson’s-like symptoms in experimental animal models, including motor impairment and loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. Oxidative stress is a key mechanism in the development of Parkinson’s. This is concerning because a previous study found that diquat generated 10-40 times more ROS than paraquat, suggesting that diquat induces oxidative stress at lower concentrations than paraquat. Whether chronic exposure to diquat increases risk and/or severity of Parkinson’s remains an open question. There is some limited experimental evidence that chronic diquat exposure may impair motor function, alter dopamine metabolism and reduce the number of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra; however, these effects have yet to be replicated by other investigators.

Environmental impacts

In the environment, diquat has a half-life of 2-10 days in water and > 1000 days in the soil, although others have reported a half-life of > 5500 days. Diquat binds strongly to organic matter and clay, which dictates its half-life in bodies of water. In sediments with a small clay fraction, diquat is more likely to remain in water for a longer period. However, in aquatic environments with sediments containing larger fractions of clay and organic matter, diquat will strongly adsorb to the soil particles, which reduces the fraction of diquat in water. While in this bound state, diquat is resistant to degradation. This is especially concerning if the same body of water is repeatedly treated with the herbicide, as this will result in the accumulation of diquat in the aquatic ecosystem over time. This has negative impacts on bottom feeders, such as crustaceans, that consume food from sediments. Although research is limited, a prior study showed that 1 ppm diquat in water was sufficient to cause mortality in various crustaceans, including Hyalella azteca, and Asellus communis. This can have adverse consequences for animals, such as waterfowl, that rely on crustaceans as a food source. According to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, diquat can also be toxic to freshwater fish.

Conclusion, data gaps, path forward

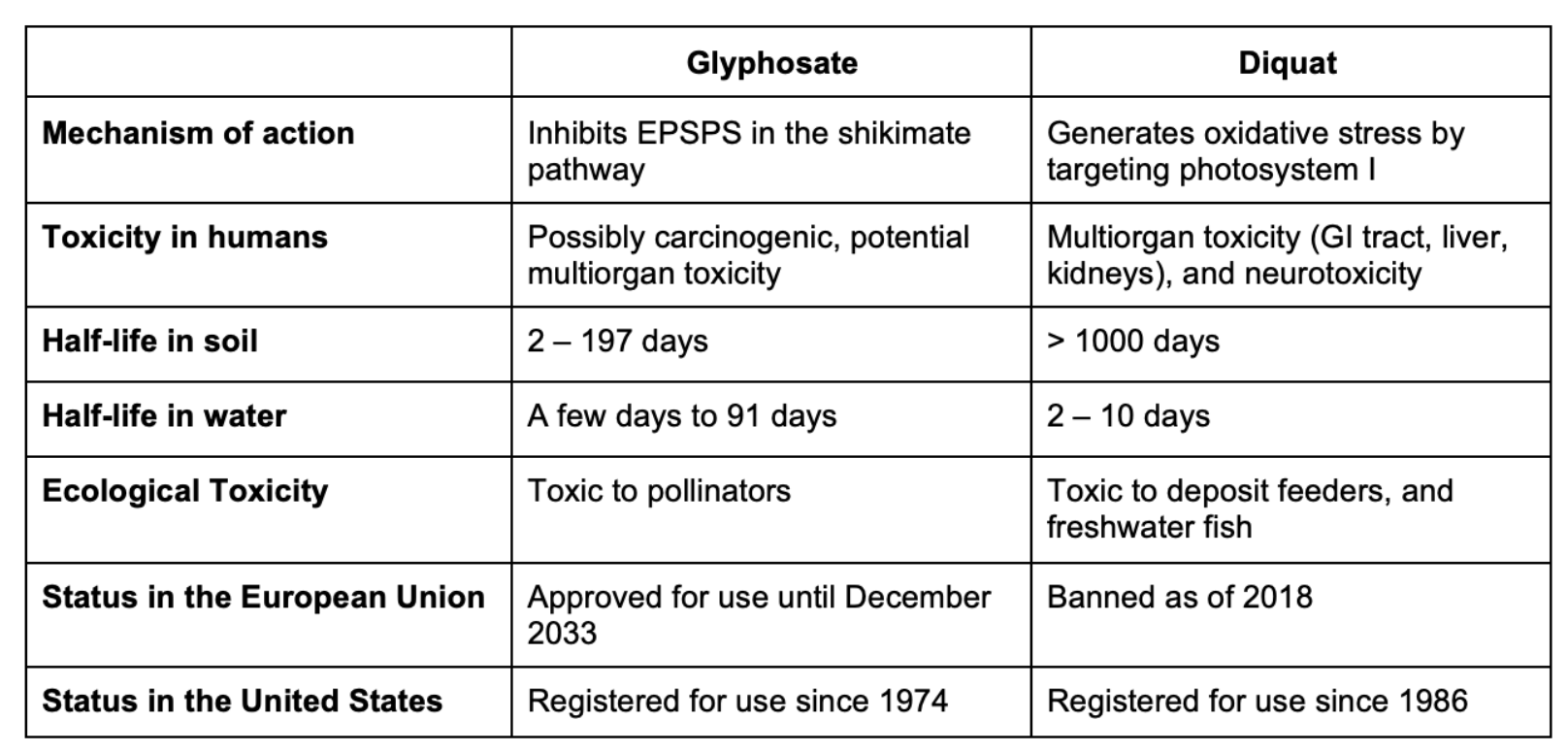

While their toxicological profiles differ, there is significant experimental and, in some cases, human evidence of acute and chronic toxicities associated with both glyphosate and diquat (Table 2). But there are significant data gaps that need to be addressed to assess the relative safety of these two herbicides. While glyphosate appears to have low acute toxicity, there is increasing experimental and human evidence that chronic exposures increase cancer risks, although the mechanism(s) by which it does so are not yet well-characterized. Diquat has significantly greater acute toxicity than glyphosate and there is evidence suggesting that chronic diquat exposure may increase risk of Parkinson’s disease, but these data are limited. Glyphosate is less persistent in the environment than diquat, but given that is use is significantly greater than that of diquat, at least at the moment, it is not clear how much of an advantage this represents.

Herbicides continue to play an important role in enhancing agricultural yield and ensuring food security in the face of contemporary global challenges, such as population growth and climate change. It is estimated that pests cause 27% to 42% loss in production of major crops around the world, and this would rise to 48% to 83% without the use of pesticides, including herbicides. In many parts of the world, excessive loss of food crops to pests may significantly increase risk of starvation, and in these situations, the cost-benefit ratio of herbicide use may be viewed as highly favorable. However, increasing evidence of the risks associated with herbicide use urges consideration of replacing the “worst actors” with less hazardous herbicides and/or developing strong regulatory policies that increase safety testing pre-market and decrease exposure post-market. The chemical manufacturing industry also needs to reconsider “business as usual” to reduce the potential for regrettable substitution by applying “green chemistry” more extensively and conducting more thorough safety testing, leveraging the rapid expansion of new approach models for higher- throughput toxicity testing.