UCL and partners are testing a simple finger-prick blood test to detect Alzheimer’s disease before symptoms, offering a cheaper, less invasive, and more accessible diagnostic approach compared to traditional scans and spinal taps

Researchers at University College London (UCL) are part of a major international study testing whether a simple finger-prick blood test can help diagnose Alzheimer’s disease even before symptoms begin.

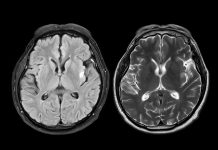

The trial will analyse blood markers linked to the condition and compare them with current PET and MRI standards, aiming to create a cheaper, more accessible screening tool for earlier intervention.

How the finger-prick test works

Currently, Alzheimer’s is detected using scans and lumbar punctures or spinal taps, which are invasive, expensive, slow, and inaccessible.

The finger-prick blood test uses a simple plasma separation card, making testing cheaper and easier to perform. It does not need to be refrigerated and can be stored and shipped to a laboratory for analysis at ambient temperature.

The test is part of the Global Alzheimer’s Platform Foundation’s Bio-Hermes-002 study and is funded by LifeArc.

A global effort to transform alzheimer’s diagnosis

The Global Alzheimer’s Platform Foundation has enrolled 883 of the 1,000 participants from 25 sites across the UK, USA, and Canada. This includes a mixture of people with good cognitive health, mild cognitive impairment, and mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease.

The finger-prick blood test will look for three known biomarkers for Alzheimer’s: phosphorylated tau 217 (pTau217), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and neurofilament light polypeptide (NfL). The results will be compared to a variety of other tests developed for Alzheimer’s, including blood-based and digital biomarkers (such as speech tests, retinal scans, cognitive tests), PET, and MRI scans.

If successful, the test could provide a scalable, accessible, and cost-effective method for screening the disease in diverse settings. This would enable earlier intervention for more people, although more evidence is needed before NHS introduction.

Professor Henrik Zetterberg of the UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, who is also a group leader at the UK Dementia Research Institute (UK DRI), is leading the team analysing test results from the UK arm of the study.

He said: “This study is unique in its size and scope, with 30% of volunteers being recruited from under-represented groups. Importantly, the results will be compared with current gold-standard diagnostic techniques. If successful, being able to diagnose Alzheimer’s with a minimally invasive, cost-effective method will revolutionise diagnostics in this area and pave the way for improved diagnosis of all neurodegenerative conditions.”

Dr Giovanna Lalli, Director of Strategy and Operations at LifeArc, said: “Over the last five years, there has been substantial progress in identifying blood-based biomarkers to identify people at high risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease before their symptoms present. Developing cheaper, scalable, and more accessible tests is vital in the battle against this devastating condition. We are committed to improving patient lives through the development of new tests and treatments, and we are excited about the prospect of a finger-prick blood test for Alzheimer’s disease because it will allow more patients to access new drugs, currently being developed, to slow disease progression in its early stages.”

John Dwyer, President of the Global Alzheimer’s Platform Foundation, said: “The introduction of the advanced dried blood spot test is highly anticipated, and LifeArc’s involvement will significantly enhance our study. Using a simple blood test could revolutionise diagnosis by making timely diagnosis accessible to more people, including those with limited access to specialised healthcare. We look forward to LifeArc’s contribution to the Bio-Hermes-002 trial.”