Exploring Earth’s deep interior has always been a challenge for scientists, although spacecraft have travelled billions of kilometres through space, humans have drilled only about 12 kilometres into Earth’s crust

Everything below that depth must be studied indirectly, using clever measurements, experiments, and computer models.

New research has revealed a surprising amount of detail about the most important hidden regions of our planet: the boundary between the mantle and the core.

A study led by scientists at the University of Liverpool shows that two massive, ultra-hot rock structures deep inside Earth have been influencing the planet’s magnetic field for hundreds of millions of years.

Two enormous blobs at the base of the mantle

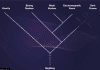

The newly identified features are immense regions of unusually hot, solid rock located nearly 2,900 kilometres beneath the surface. One lies beneath Africa and the other beneath the Pacific Ocean. Each structure is roughly continent-sized and surrounded by a ring of cooler rock that stretches from the North Pole to the South Pole.

These formations sit just above the liquid outer core, a swirling ocean of molten iron. This liquid metal generates Earth’s magnetic field through a process known as the geodynamo. Until now, scientists had assumed that the boundary between the mantle and the core was relatively uniform. The new findings challenge that idea.

How Earth’s magnetic field records deep history

Earth’s magnetic field leaves behind traces in rocks as they form. Minerals can lock in the direction and strength of the magnetic field at the time they cool, preserving a record that can last for hundreds of millions of years. By studying these magnetic signatures, scientists can reconstruct how the field behaved in the distant past.

In this study, researchers combined these palaeomagnetic records with advanced computer simulations of the geodynamo. The models recreated how molten iron moves within the core and how heat flowing from the mantle above affects that movement. Running such simulations over geological timescales required enormous computing power.

The results show that the top of the outer core exhibits strong temperature gradients rather than a smooth heat distribution. Hot regions occur beneath the two massive mantle structures, while cooler areas exist elsewhere.

In hotter regions, the liquid iron appears to move more slowly, or even to stagnate, compared to the more vigorous flow beneath cooler parts of the mantle. This uneven flow has left a long-lasting imprint on Earth’s magnetic field. Some features of the field have remained stable for hundreds of millions of years, while others have shifted dramatically.

Rethinking Earth’s long-term magnetic behaviour

For decades, many areas of Earth science have assumed that, when averaged over long periods, Earth’s magnetic field behaves like a simple bar magnet aligned with the planet’s rotation axis. The new findings suggest this assumption may not be entirely accurate.

If the magnetic field has been persistently distorted by deep mantle structures, it could affect how scientists interpret ancient continental movements, climate patterns, and biological evolution. It may also influence theories about the formation of natural resources that depend on Earth’s internal dynamics.

A look into the deep Earth

By linking ancient magnetic records with modern simulations, the study strengthens the case for using Earth’s magnetic history as a tool to understand the deep planet.

These results offer a rare glimpse into processes occurring thousands of kilometres beneath our feet and highlight how deeply connected Earth’s surface history is to its hidden interior.

The research was carried out by the DEEP research group at the University of Liverpool, in collaboration with the University of Leeds, and published in Nature Geoscience.