Dr Christopher Gilbert at Biena Consulting Srl offers a comprehensive overview of the EU Deforestation Regulation, which aims to reduce the European Union’s contribution to deforestation, thereby minimising greenhouse gas emissions and combating global biodiversity loss

Forests are carbon sinks and deforestation, therefore, contributes to global warming by reducing carbon sequestration. The EU Deforestation Regulation (hereinafter referred to as the EUDR) aims to minimise the EU’s contribution to deforestation, thereby reducing the EU’s contribution to greenhouse gas emissions and global biodiversity loss.

Europe itself is experiencing net reforestation as marginal farmland reverts to forest, so deforestation is not a European problem in the first instance. However, Europe is a major importer of commodities which have contributed to deforestation, mainly in tropical countries.

The Regulation aims to achieve its objectives by requiring that the import or sale of seven listed commodities within the EU must be guaranteed to have been produced on land free from deforestation. The Regulation will come into force on 30th December 2025 (delayed by one year from 2024) and applies to all products produced after 29th June 2023. The seven EUDR commodities are cattle, cocoa, coffee, natural rubber, palm oil, soy and timber. The Regulation embraces semi-processed derivatives of these commodities – leather as well as beef, chocolate, as well as cocoa beans, etc.

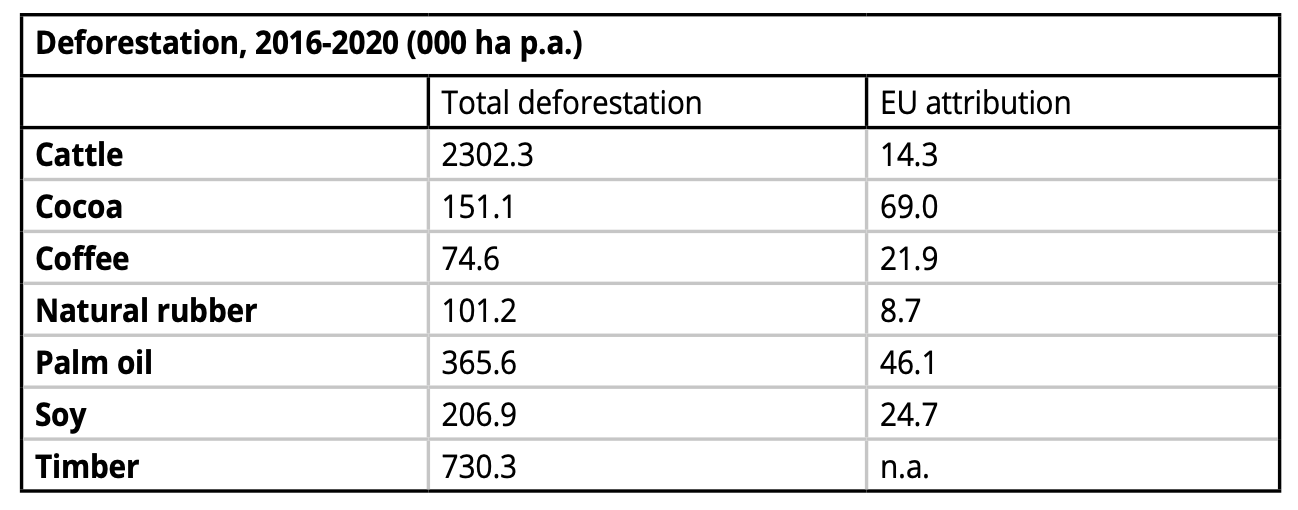

Around three-quarters of global deforestation can be attributed to the felling of forests for agricultural production. The table shows estimated deforestation averaged over the five years 2016-2020 for the seven EUDR commodities. The second column of the table reports attributions of these deforestation numbers to EU imports of the EUDR commodities. The numbers attempt to answer the question, How much deforestation in the EU is responsible for through its commodity imports? Cattle ranching is the most important driver of deforestation, but Europe is not a major beef importer. In terms of EU imports, cocoa and palm oil are the most prominent.

How will the EUDR work?

Europe produces its own beef, some timber and small amounts of soybeans, but for the most part, these seven commodities are imported. EUDR compliance, therefore, focuses on imports. Importers are required to submit detailed due diligence statements. This information should enable the produce to be traced back to the producing farms and demonstrate that these farms are not operating on deforested land. “Deforestation-free” is interpreted as not subject to deforestation since 31st December 2020, as demonstrated by the location of the producing farms on high-resolution satellite maps of the origin country, both currently and before 2021. The governments of the major exporting countries have invested resources to ensure the availability of these maps.

Commodity supply chains are complicated. The cocoa and palm oil supply chains are both characterised by a large number of independent farmers, many of whom are smallholders, together with a large number of European producers of final products (chocolate and chocolate confectionary in cocoa, “fast moving consumer goods” in palm oil). A small number of large exporters and processors sits between the two groups. This “hourglass” structure is shared, albeit to a lesser extent,

by the other EUDR commodities.

The practical problem is to maintain traceability as the farm-level produce is aggregated for export and processing. For example, West African cocoa beans are invariably bulked and exported either in containers or bulk carriers. A 40-foot (12.2 m) container carries around 25 tonnes of cocoa beans, which may have been produced on around 400 farms. A bulk carrier will take around 5,000 tonnes of beans, which may have been grown on approximately 80,000 farms. Maintenance of traceability requires a blockchain-type system.

EU member governments have the obligation to monitor compliance. The rigour of the compliance checks depends on the risk classification of the exporting country. The EU has designated four countries as “high risk”, entailing intensive checks, but they account for a very low proportion of the EU imports. One hundred forty countries have been classified as low risk, entailing only low levels of compliance checking. These include all the EU member states, the UK, and the U.S. Fifty countries, including Brazil, Côte d’Ivoire, Indonesia, and Malaysia, which are seen as responsible for substantial deforestation, are classified as standard risk.

Who will be affected by the EUDR?

There are two sides to this question – who will be affected in the producing countries, and how will European consumers be affected?

Without assistance, smallholder farmers will be unable to ensure EUDR compliance, and many may remain unaware of its existence. The effects in the producing countries will, therefore, depend on the degree to which the sector is organised. Governments should ensure the availability of the required maps, and multinational exporters, who are often also processors, will wish to ensure sufficient compliant supplies to meet their requirements. Nevertheless, some producers may fail to comply, either because they are producing on deforested land or because they are located in remote or minor producing countries where the required organisation is lacking. Non-compliant producers will be obliged to sell into non-European markets or to illegally disguise their produce as coming from a compliant property.

The EUDR may generate unintended collateral impacts:

- Exporters may prefer to operate with large-scale farmers and plantations.

- Major multinational exporters and processors may gain market share as smaller, nationally based exporters and processing companies find EUDR compliance particularly onerous. The hourglass constriction will further tighten.

- Multinational exporters may increase their “up-county” presence, cutting out local intermediaries to simplify compliance.

- The administrative burden imposed on European dairy and soybean producers, all of whom will be covered by the EUDR, may lead some to switch to less regulated activities.

There will, therefore, be winners and losers. Nevertheless, comprehensive traceability will prove a long-term benefit, particularly in allowing governments to more effectively regulate their sectors, both in limiting illegal production and in avoiding surges of production that can disrupt the global supply-demand balance.

The main impact on European consumers is that they may need to pay a premium over world market prices to persuade exporters to meet EUDR compliance imposes costs rather than sell into non-European markets. One estimate indicates that in cocoa, these costs might amount to 1% of the total product value, which is small in relation to normal price variation. We will need to wait until 2026 to see whether this is the case.

How does this all apply to consumers in near-EU countries such as the UK? The UK has planned its own deforestation regulations, but these appear likely to be less comprehensive and exacting than the EUDR. However, this post-Brexit freedom is likely to prove nugatory.

In her 2020 book “The Brussels Effect”, Anu Bradford has argued that, in certain industrial contexts, there is a regulatory “race to the top” (1) since firms are forced to choose between compliance with the most exacting set of regulations in the countries in which they sell, or alternatively, retreat from the highly regulated markets. A UK chocolate manufacturer that wishes to export to the EU will need to meet the EUDR requirements irrespective of UK regulations.

Will the EU Deforestation Regulation achieve its deforestation objectives?

This must be the acid test for the EUDR. Governments have never enjoyed success in influencing production from established tree crops. Once trees are in existence, farmers will harvest and sell the crop, even if this means diverting to a non-traditional market or disguising their produce as compliant. Where the EUDR has leverage is in investment (planting) decisions rather than in production itself.

We can think of a farmer or an exporter as balancing the costs and benefits of complying with the EUDR and selling in Europe against those of selling in alternative markets. Exporters’ calculations will depend on their circumstances (location, relationships, national historical ties, etc.).

We can expect exporters in countries that have traditionally sold in Europe to continue doing so, particularly if governments, producer organisations, and multinational traders assist in that process. However, exporters in countries which have hitherto sold little to Europe will generally avoid paying for EUDR compliance and will sell elsewhere. This will be reflected in investment decisions.

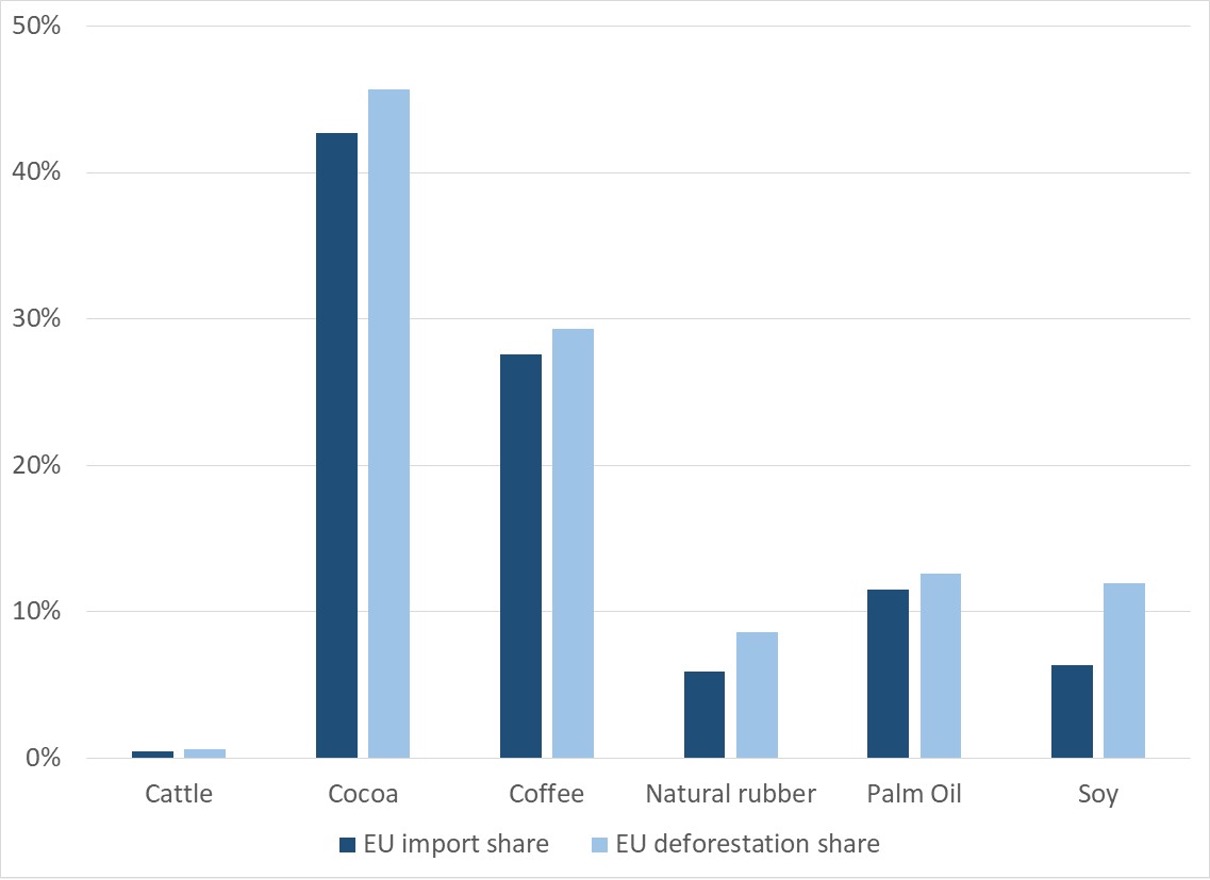

EU import shares may, therefore, provide a measure of the extent to which EU rules will influence production and planting decisions in the producing countries. The figure shows the EU’s import shares of world production, averaged over 2016-2020 (dark bars). It also shows (light bars) deforestation attributed to the EU as a percentage of total deforestation for each commodity. The six commodities charted fall into four groups:

- Cocoa and coffee where Europe is the major importing region and where exporters will attempt to maintain their presence;

- Cattle, where European imports are small as a proportion of total production and diversion to non-European markets will be simple; and

- Natural rubber, palm oil and soybeans, where European imports are modest.

On this basis, we should expect the greatest influence of the EUDR to be in cocoa- and coffee-producing countries. In countries that have traditionally exported to Europe, such as West African cocoa producers, compliance is likely to be the norm and deforestation levels should fall. The net effect on global deforestation levels will depend on the extent to which production migrates over time to countries with weaker information and controls.

In the intermediate group of countries, exports to Europe are likely to require a premium to cover compliance costs. The EUDR will effectively become voluntary in the sense that some exporters will opt into compliance to obtain the European premium while others will ignore the EUDR and export to non-European markets. Producers who wish to expand into forest land will face little constraint in doing this. Finally, we should not expect the EUDR to have a significant impact on deforestation for cattle ranching, where European leverage is minimal.

In summary, the EUDR may contribute to reduced deforestation in cocoa- and coffee-producing countries with strong European links. It is unlikely to have any substantial impact on deforestation in the other EUDR commodities.