Natasha Constantinidou unpacks Ancient Greek heritage in (early modern) Europe through the project Greek Heritage in European Culture and Identity

The heritage of ancient Greece is widely recognised as a ‘pillar’ of European culture and identity. However, the complex historical processes of cultural reception and appropriation that have shaped this notion remain not fully understood.

Today, references to Greek culture permeate Europe’s urban spaces, artistic creations, political life, and everyday objects. But when did the Greek past become part of the broader ‘European’ past and a shared reference point for Europe’s peoples? How did it acquire renewed relevance in the present? Who participated in this transformation, and what form did it take?

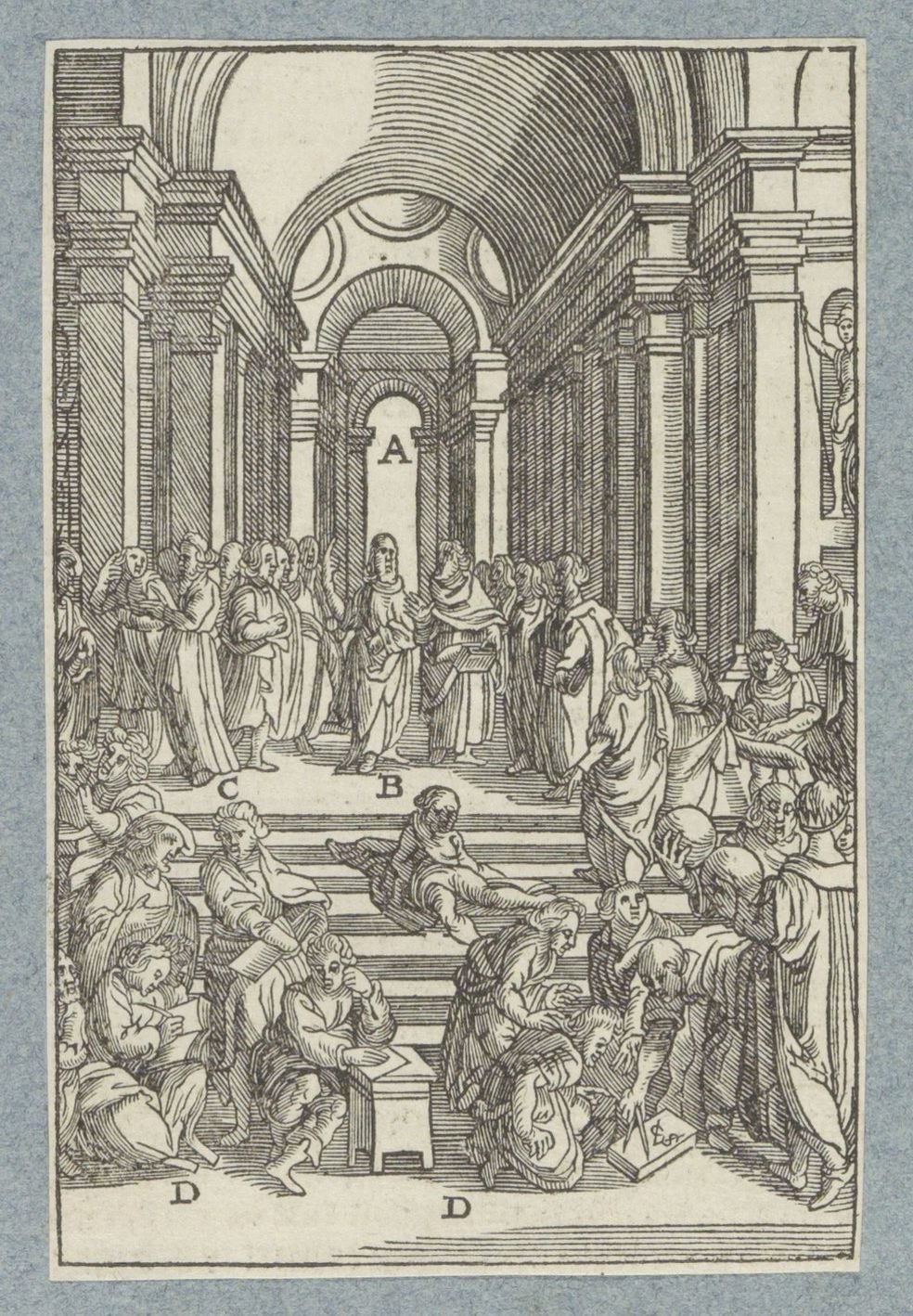

The fascination with Greek culture can be traced to the early modern period, from the Renaissance until the eighteenth century. During this era, European scholars – and later educated elites and a growing public – encountered the Greek classical language and heritage primarily through education, religion, and the lay sphere.

This engagement influenced European languages and literatures (and the field of philology), shaped religious and political thought, affected material culture, and spread rapidly with the rise of printing and publishing in the sixteenth century. Interest in Greek heritage continued across the centuries, reflected especially in the rediscovery of ancient sites by Grand Tour travellers between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries.

Greek Heritage in European Culture and Identity

The HORIZON-WIDERA-2021 ACCESS project, Greek Heritage in European Culture and Identity (GrECI, GA no. 101079379) explores the reception and appropriation of ancient Greek culture in early modern Europe, spanning from the so-called ‘rediscovery’ of Greek language, literature and wisdom, to their integration into the European cultural landscape between the 15th and 17th centuries.

Through the collaborative effort of three partner institutions: the University of Cyprus, the University of Oslo in Norway, and the Université Marie et Louis Pasteur in France, the GrECI team has been studying this subject from four distinct perspectives: the spread of Greek learning through early Greek printed books (history of the book), digital codification of early modern impressions of Greek material culture (material culture/digital heritage studies), the use of Greek language in the construction of identities (language and literature studies), and the use of Greek during different phases of the Reformation (intellectual history).

Ancient Greek culture in the early modern period

From the early sixteenth century, the spread of Italian Renaissance humanism made Greek learning a core element of (elite) education across Europe, embedding it in what was seen as a ‘shared’ European past. Students who could afford schooling encountered a common curriculum that, alongside Latin authors, included Aristotle, Isocrates, Lucian, Basil of Caesarea, Xenophon, Plutarch, Aristophanes, Demosthenes, and Homer, to name but a few.

Greek also gained prominence amid religious reform and confessional conflict. Thinkers such as Erasmus, Valla, Lefèvre d’Étaples, Luther, and Melanchthon, emphasised Greek as essential for understanding Scripture and pursued translations aimed at recovering the ‘pure’ Biblical Word. Both Protestant reformers and the Catholic Church invoked early Christianity to legitimise their respective – even if conflicting – positions.

Greek heritage further shaped emerging national identities. Some scholars claimed linguistic or ethnic ties to ancient Greece to assert cultural superiority, while others rejected such associations. Western Europeans even sought archaeological evidence of Greek colonies, such as at Marseille. In these ways, Greek texts, ideas, and artefacts became central to major cultural and political debates of the early modern era – from humanist educational reform and the Reformation to the rise of vernacular languages and national discourse, while at the same time serving as one of the main pools from which scholars and polemicists could draw arguments from.

The GrECI project focuses on four main areas

Building on these considerations, the interdisciplinary and collaborative GrECI project centred on four main areas. First, it examined the dissemination of Greek texts through the production of Greek-language books in Western Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, assessing a selection from the several thousand editions printed in centres such as Venice, Paris, Basel, Geneva, Antwerp, Strasbourg, and Leipzig. Second, to explore how Greek language and literature shaped debates over emerging national or ‘vernacular’ cultures, the project analysed a series of comparative case studies of treatises that supported the relationship between vernacular languages and Greek.

A third area investigated the role of Greek learning in the religious controversies and confessional conflicts of the era, tracing how Greek texts informed theological debates and served as shared reference points in the formation of religious identities.

Finally, the project examined Europeans’ direct encounters with the material remains of ancient Greece, evaluating how early modern travellers responded to classical monuments and how these experiences contributed to the construction of European identities. This resulted in dynamic digital maps that reflect travellers’ impressions when encountering ancient sites.

A dynamic role – and lessons for the present

Taken together, this research highlights the dynamic role of ancient Greek culture in the early modern period – functioning both as a shared point of reference and as a source of cultural differentiation. In many ways, it mirrors modern dynamics in which identities are sometimes framed in terms of a common European heritage and at other times asserted in contrast to it.