Leonardo Testi, Ugo Lebreuilly, Elenia Pacetti, Anaëlle Maury, Veronica Roccatagliata, Patrick Hennebelle, Ralf Klessen, and Sergio Molinari investigate the initial conditions for planet formation in this special astronomy focus

The origin of the diversity of planetary systems

Understanding the origins of our own Solar System and determining whether it is a common or rare occurrence in the cosmos is a fundamental question in modern astrophysics, as well as a topic of general interest to human society.

Following the first discovery of exoplanets in the 1990s, it has become clear over the past three decades that most stars host planetary systems. Yet, exoplanetary systems have a broad variety of architectures, and our own system architecture does not appear to be one of the most common ones in our Galaxy.

One of the current challenges in this field is to understand whether this diversity stems from a variety of initial conditions. This is particularly relevant for addressing the question of the fraction of planets that may develop the conditions for long-term habitability.

Planets form within “protoplanetary disks”, which are created as a byproduct of the gravitational collapse of diffuse interstellar material during the star- formation process. Current research focuses on the characterisation of the chemical and physical conditions of these protoplanetary disks and on the question of how these can influence the type and properties of planets that may form in these disks.

The initial conditions of protoplanetary disks are determined by the physics of cloud fragmentation and collapse, by the evolution of refractory and volatile material in this highly dynamical phase, and by the impact of feedback from the newly formed stars. Here, the interplay and comparison between numerical simulations and observational constraints are essential to constrain the (unobservable) microphysical processes in concert with their global large-scale observational consequences.

The initial conditions for planet formation

Within our international team of researchers, we investigate the formation of protoplanetary disk populations in molecular clouds using multiscale numerical simulations. These incorporate diverse physical processes, including gravity, radiation and magnetic fields. Gravity is responsible for the formation of stars. Combining free-falling matter with rotation leads to the disks. Radiation is key to predicting the disk temperature and the cloud fragmentation at all scales.

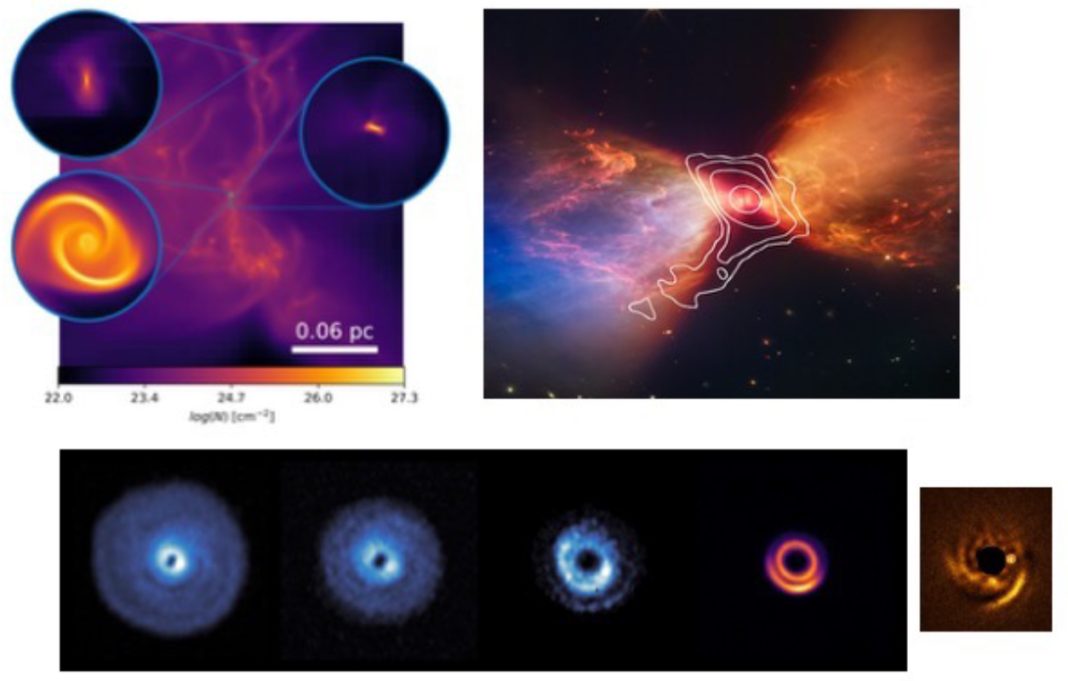

Our simulations simultaneously model phenomena at cloud scale and at disk scale, allowing us to predict the diversity of young disks and their interaction during their infancy. We found, for example, that the magnetic field acts against the rotation, reducing the typical disk sizes. This is necessary to reproduce the observed distribution of disk radii.

Because the youngest stellar objects (also called protostars) are very complex in their structure and time evolution of the different layers composing them (core, envelope, disk, outflow and at the smallest scales the protostellar embryo), it is key to be able to compare the predictions from theoretical models to observed populations of young protostellar disks.

Since astronomical observations probe the structure indirectly thanks to the radiation of matter, making synthetic observations of the physical models, for example, producing both the dust thermal emission and molecular line emission maps, is a powerful approach for measuring the physical properties of disks by leveraging detailed predictions from simulations and radiative transfer models, then matching them to real data.

By processing model outputs with tools that simulate instrumental response (like ALMA), we can directly compare quantities: such approaches have allowed us to show that most of the youngest disks are still very compact in sizes, yet their masses and temperatures remain difficult to capture.

Moreover, the role of magnetic fields was highlighted by such detailed studies, showing that in both individual prototypical objects and in populations of observed disks, some of the disk properties can only be reproduced with a scenario where magnetic braking redistributes efficiently the angular momentum during the star and disk earliest formation stages. Finally, grain growth at various scales and dust settling signatures in disks are probed by matching millimetre continuum spectral indices and polarisation patterns with model expectations.

Constraints from new Observations

Three key players are at work to regulate the formation and early evolution of the disks around young stars: turbulence, gravity, and magnetic fields. Unfortunately, none of these physics actors is easy to observe directly, only through the indirect effect they have on the kinematics and distribution of matter, which in turn can be observed through the emitted radiation. Thus, to test these combined effects, we have used observations to compare and constraint state-of-the-art numerical models. The state-of-the-art instruments to observe the Cold Universe and the warm matter close to the protostars are ALMA and NOEMA in the microwaves and JWST and the VLT in the optical/ infrared. Our observations have revealed a diversity of young (<100;0000 years old) disks, yet most of them are extremely compact (<40 au), probably massive (>0.1 Msun), warmer than expected (with temperatures reaching several hundreds of K in some cases), and still very strongly accreting from their disk/envelope.

Magnetic fields are difficult to observe, yet we have shown their role is key. These fields thread through the collapsing core, and we have shown that they act as a brake, carrying away angular momentum from the reservoir material as it travels from the outer core to the disk-forming scales (<50 au), through processes known as magnetic braking. As part of ECOGAL, we have started a new large observational effort with NOEMA and ALMA to provide direct observational constraints on the importance of magnetic fields in the formation of protoplanetary disks.

Emerging planetary systems

The formation and evolution of planets are closely linked to the physical and chemical history of their natal protoplanetary disc. As the disc evolves through gas transport, dust growth, radial drift, and chemical processing, the distribution of solids and volatiles changes over time, shaping the material available for planetary accretion. Our international team develops models that couple the dynamical and chemical evolution of discs with the growth and migration of planets, capturing how their mutual interaction governs both orbital evolution and emerging planetary composition.

These models trace how the evolving disc environment imprints distinct elemental and molecular signatures on growing planets. Emerging planetary architectures and bulk chemical composition of planets can then be used to validate the models and place constraints on the processes that shape the diversity of planetary systems.

Detailed observations with ALMA and the VLT of the structure of protoplanetary disks reveal the disturbances induced by the formation of planets and their interaction with the disks, and potentially the presence of planets themselves. Our team is engaged in the characterization of these structures and the emerging planets. These will provide the key tests for the models.

Ultimately, these approaches open a path towards understanding the processes that shape the properties of exosystems and understanding whether our own Solar System is a common outcome or a rare exception in the Galaxy.