Erik Green examines the complex interactions between the Khoekhoen and early European settlers, challenging conventional narratives of indigenous passivity and highlighting the resilience and agency of Khoe societies in the face of colonial pressures

From the sixteenth century onward, European powers gained territorial control over vast regions across the globe, followed by substantial waves of migration. By the end of the eighteenth century, roughly 1,410,000 Europeans had settled overseas (Altman and Horn 1991). While some areas – such as the Americas – attracted more migrants than others, a significant number also settled at the Cape of Good Hope. There is now a broad scholarly consensus that the establishment of European settler societies had lasting consequences for the economic development of the regions in which they took root. Some scholars argue that European settlers brought with them, or pressured colonial authorities to adopt, inclusive institutions that fostered long-term economic development (Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson 2002; Engerman and Sokoloff 2002). Others, such as Veranci (2013), contend that settler colonialism represented a form of “die-hard colonialism” that marginalized – and in some cases eliminated – indigenous peoples. Carlos, Feir, and Redish (2022), using the United States as a case study, argue that institutional and economic change cannot be fully understood without accounting for the fate of indigenous communities.

While it is well understood that indigenous peoples in settler colonies were eventually marginalized, far less is known about how these processes unfolded in practice. Research from the United States, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand shows that indigenous communities did not immediately lose their agency. Instead, they resisted and adapted to colonial rule in multiple ways (see Cavanagh and Veracini 2017). Their agency, in turn, shaped the emergent institutional fabric of settler societies (Green 2022). Yet, despite offering rich qualitative insights, these studies – constrained by limited source material – often struggle to provide detailed explanations for the processes that ultimately led to indigenous dispossession.

Cape of Good Hope Panel research program

Within the Cape of Good Hope Panel research program (www.capepanel.org), Dr. Calumet Links and Professor Erik Green are applying novel methodological techniques to uniquely detailed historical sources to study the processes that ultimately led to the collapse of Khoe societies as independent political units at the Cape.

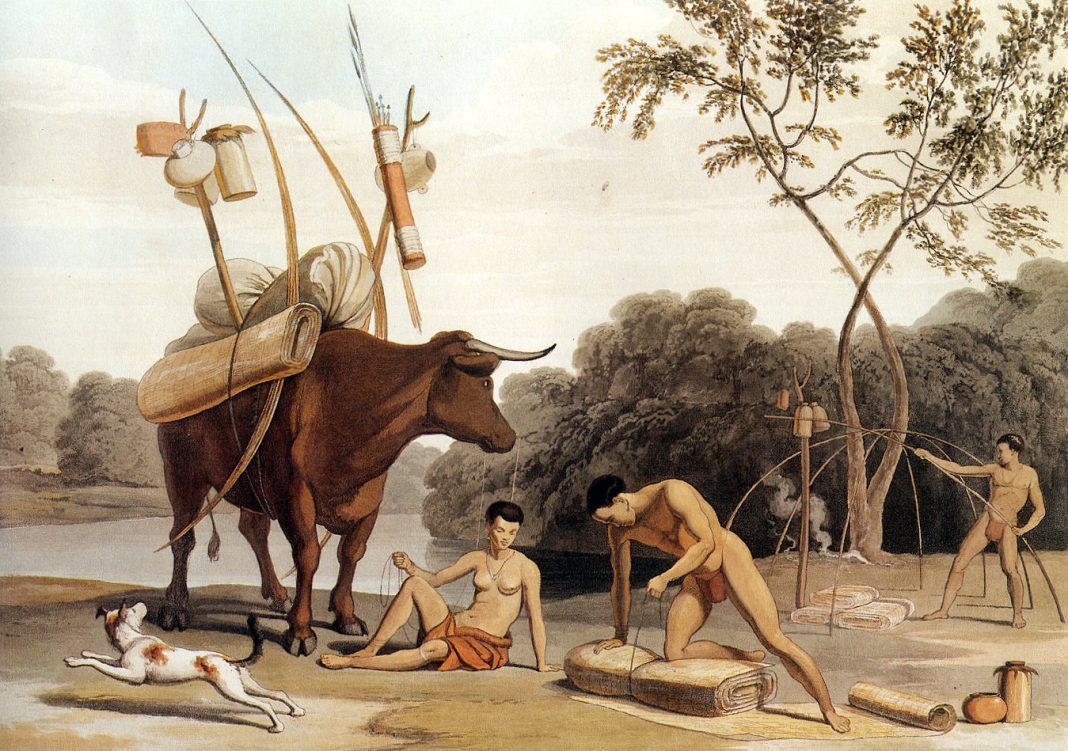

In 1652, the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC) established a refreshment station at the Cape. Its official aim was to secure more reliable trading relations with the Khoe and to monopolize local trade, particularly against French and British competitors. The VOC explicitly declared that it had no intention of expanding territorial control beyond the station, citing financial constraints. Nevertheless, territorial expansion occurred, for reasons discussed elsewhere (e.g., Green 2002). This expansion was made possible in part by the weakening of Khoe societies. The central question is how this weakening occurred.

In current work, we use new techniques to convert written text into numerical data across a vast body of sources, combined with close reading of selected qualitative materials. Together, these methods allow us to study the fate of the Khoe at the Cape at a more granular level than has previously been possible. The core sources for our study are the Dagregisters (day registers), produced by the VOC from 1650 to 1795. These daily records contain observations relevant to colonial administration – ranging from weather conditions to illness and food supplies. Crucially, they also document interactions between VOC officials and specific Khoe groups.

We have constructed a text corpus that enables us to track references to Khoe leaders, polities, conflicts, disease, and trade. This allows us not only to examine VOC-Khoe interactions in general, but also to follow relationships with individual Khoe polities and to observe how these relationships changed over time – a key dimension given that VOC expansion and rule were shaped by shifting alliances and divide-and-rule strategies.

Research findings

Although still preliminary, our findings suggest that we need to reconsider both the early VOC-Khoekhoen encounter and the causes of the Khoekhoen’s subsequent loss of independence. Historians of the Cape generally agree that most Khoe communities – despite resistance – were relatively quickly subordinated to colonial authority.

Yet a closer reading of the existing literature reveals that our understanding of why this occurred remains limited. Two explanations appear most frequently: the VOC’s superior military technology and the impact of disease. The conventional view is that the VOC’s access to firearms and horses enabled it to defeat individual Khoe groups with relative ease, thereby undermining Khoe economic and political structures. The smallpox epidemic of 1713 – estimated to have reduced the Khoe population by roughly 30% – is often portrayed as delivering the final blow to Khoekhoen independence.

Our preliminary results, however, show no indication that conflicts between the VOC and the Khoe declined over time, as one would expect if the Khoe had been decisively defeated militarily. Mentions of violent encounters remain remarkably stable. Although the nature of these conflicts changes over time – from organized attacks to raiding – there is no evidence that Khoekhoen resistance collapsed in the early eighteenth century, contrary to earlier interpretations. A similar pattern emerges regarding disease and mortality: references to illness and death remain consistently high throughout the period, with no noticeable spike around the smallpox epidemic and no clear indication of a corresponding collapse in Khoekhoen societies.

Reconstruct and rewrite the history of the Khoe at the Cape

These initial results do not yet offer a definitive explanation for the fate of the Khoekhoen. However, the quantitative patterns strongly suggest that we must return to the original qualitative sources in order to reconstruct – and likely rewrite – the history of the Khoe at the Cape. To cast the Khoekhoen merely as passive victims who were easily defeated, or to reduce them to a marginal group struggling at the edges of colonial society, is to deny their history and to produce an incomplete understanding of the development of the Cape Colony. More exploratory work is needed.