Principal Investigator, Professor Helen Fulton, Chair of Medieval Literature at the University of Bristol, explores a collaborative project which aims to revitalise a forgotten British borderland

Where is the March of Wales? The term refers to the borderlands between Wales and England, but the area of the March is not officially defined or recognised as a region of Britain.

Our project aims to retrieve the Welsh borderlands and create a new sense of regional identity which will facilitate tourism, business growth, cross-jurisdictional initiatives, and heritage preservation.

From 1536, when the political border between Wales and England was established by Henry VIII, the two nations have been divided into separate jurisdictions and, since devolution in 1999, separate governments. People and organisations in the borderlands are classified as ‘Welsh’ or ‘English’ regardless of their cultural and linguistic identities.

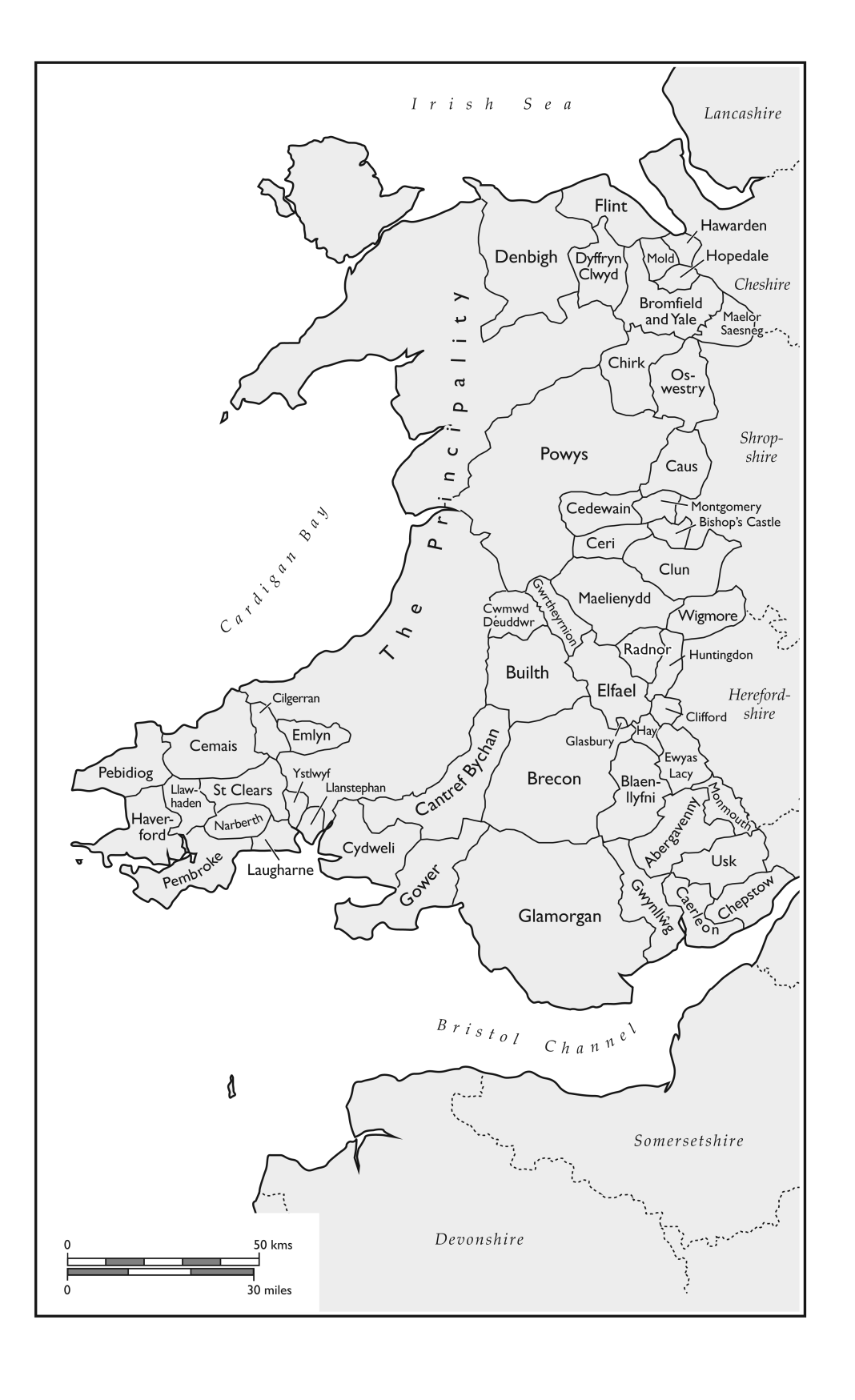

By exploring Marcher society before the political border was imposed in 1536, our project, MOWLIT, ‘Mapping the March: Medieval Wales and England c. 1282–1550’, will investigate the culture of the Welsh Marches, both the eastern March, along the modern border, and the less well-known southern March that stretched the full length of the south coast of Wales.

These ‘Marches’ (a word of Germanic origin, found in Old English mearc, ‘border’) began to take shape from the time of the Norman conquest of England and Wales in 1066. Norman barons were rewarded with vast tracts of land in eastern and southern Wales, and their new stone castles and small towns soon dominated the landscape. By 1282, when Edward I conquered independent Wales, historical records were referring to ‘Wales and the Marches’ as two distinct regions. When Henry VIII formally annexed Wales in 1536, the Marcher lordships were dismantled and replaced by the English-style counties that we know today.

We are examining the records of medieval Marcher society to look for evidence of a distinctive regional culture and identity. We know that French-speaking Normans, English, Welsh and other linguistic groups lived side by side in the Marches, that conflict and violence were rife within and between different groups, and that relations between Welsh and English varied from outright hostility to co-operation, intermarriage, and assimilation. Does a distinctive regional identity still survive in the modern March of Wales, and, if so, how is it manifested?

Our methodology

At the centre of our research is a large database of information about the medieval Marches of Wales, including the people, places, texts, and manuscripts, and how they interacted with each other. We are using existing catalogues and historical records about the Marcher lordships, most of which are held in archives such as The National Archive in Kew, the British Library in London, and the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth.

With the help of software engineers, our postdoctoral researchers, Dr Rachael Harkes and Dr Matthew Lampitt, are entering the data into a custom-made data management application, hosted by the University of Bristol. We are also building a website, in collaboration with a user experience (UX) consultant and a graphic designer, which will eventually host all the data in an easily searchable format.

Researchers will be able to find connections between the people and places of the medieval March and trace the movement of texts and manuscripts, in Welsh, English, French, and Latin, around the regions of the March, indicating the cultural and linguistic priorities of Marcher communities.

Mapping the March

One of the most innovative aspects of the project is a series of digital maps of the Marcher lordships. Working with our project partner, the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, we will create maps showing the changing shapes and ownership of the lordships at fifty-year intervals, tracing the history of Marcher land grants and the structures of the English aristocracy. This is the first time that the geographical spaces of the lordships have been accurately mapped, and the information will help researchers to understand the contours of the March, patterns of ownership, and interactions between Marcher lords and Welsh gentry.

Our digital maps are based on the earliest Ordnance Survey maps from the late nineteenth century, augmented by parish maps, tithe maps, estates maps, and enclosures, and further boundaries can be added as we find more information from historical records. We are also drawing on the resources of the Royal Commission, whose cartography experts have already mapped most of the parish boundaries of Wales.

Public engagement and outreach

In addition to a project website, we have created two short videos explaining the project and an extensive mailing list encouraging stakeholders to engage with the project. We have started an annual series of lectures, delivered in person and online, which are recorded and uploaded to YouTube. We have partnered with the Mortimer History Society to stay in touch with communities in the modern March of Wales.

We welcome comments and queries from academics, policy makers, local historians, and members of the public – you can get in touch with us by emailing: mapping-the-march@bristol.ac.uk