Jean C. Pfau and Tracy McNew from the Center for Asbestos-Related Disease address the legacy of environmental asbestos, which continues to pose a public health risk

Asbestos forms whenever heat, water, and minerals combine through metamorphic and hydrothermic processes to create fibrous mineral crystals. This fibrous structure has led to its use throughout human history as a fire retardant and insulation material that can be woven into many products, from brake linings and tiles, to coats and oven mitts. Because it is a natural component of rock, the fibers can be released and enter the air as dust whenever humans or nature disturb the rock.

The term “asbestos” refers specifically to six types of mineral fibers that can be used for commercial purposes, all of which cause deadly diseases, including multiple cancers, lung scarring (fibrotic) diseases, and autoimmune diseases. (1,2,3) Importantly, similar fibers also cause these diseases, including Libby Amphibole (LA), erionite, and fluoro-edenite. For example, mesothelioma occurs in places where exposures are simply due to rock disturbance and blowing dust. (4)

Many people seem to believe that asbestos has been “banned” in the U.S. This belief is incorrect. First, asbestos cannot be banned entirely because it is naturally present in many rocks and soils. Mining of vermiculite, talc, iron, and other ores brings up asbestos fibers out of the rock. In areas like southern Nevada and parts of California, building roads, homes, and cities, as well as exposure to natural disasters, and riding 4-wheelers or horses, can expose people to asbestos. (5) Mineral fibers in the rocks and soils near Lake Mead, Arizona, contain fibers that elicit more severe autoimmune and lung outcomes in mice than LA. (6)

Second, while some U.S. bans occurred decades ago, most have been overturned, allowing the import and use of large quantities of asbestos products. These bans were likely terminated due to the commercial value of the products, and the belief that undisturbed asbestos-containing materials are relatively safe. However, no precautions were taken to address the fact that remodeling, demolition, fires, aging, and natural disasters disturb the material, releasing respirable fibers into the air. Such exposures occur even in countries where broad asbestos bans are in place, due to the residual, historical presence of “legacy asbestos”.

Legacy asbestos

“Legacy” asbestos refers to the many asbestos materials that remain in buildings, infrastructure, and products put in place years ago. Millions of aging buildings in the U.S. still contain asbestos, including Libby’s vermiculite. Even buildings constructed in recent decades may contain asbestos building materials. The Asbestos Disease Awareness Organization (ADAO) has stated that the risk from legacy asbestos to families, construction workers, firefighters, teachers, and many others is unacceptable. (7)

In March 2024, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) finalized restrictions on the import and some uses of chrysotile (8) but did not address other types of asbestos and exposures. The ADAO, public health agencies, and healthcare professionals filed legal claims against the EPA for its failure to address these exposures. In response, the EPA initiated a “Part 2” evaluation of asbestos risk, stating that the court had ruled that “the agency unlawfully excluded ‘legacy uses’ and ‘associated disposal’” from its risk evaluation.

The Part 2 evaluation includes chrysotile, crocidolite, amosite, anthophyllite, tremolite, actinolite, LA (and its tremolite, winchite, and richterite constituents), and asbestos- containing talc. (9) The new EPA assessment, released in 2024, states that “disturbing and handling asbestos associated with legacy uses, and asbestos as a chemical substance, poses unreasonable risk to human health”. (10) Notably, the EPA is evaluating LA, winchite, and richterite as forms of asbestos. This is a significant step forward in recognizing non-commercial mineral fibers as asbestos due to their potential to cause disease.

Legacy exposures in Libby, Montana

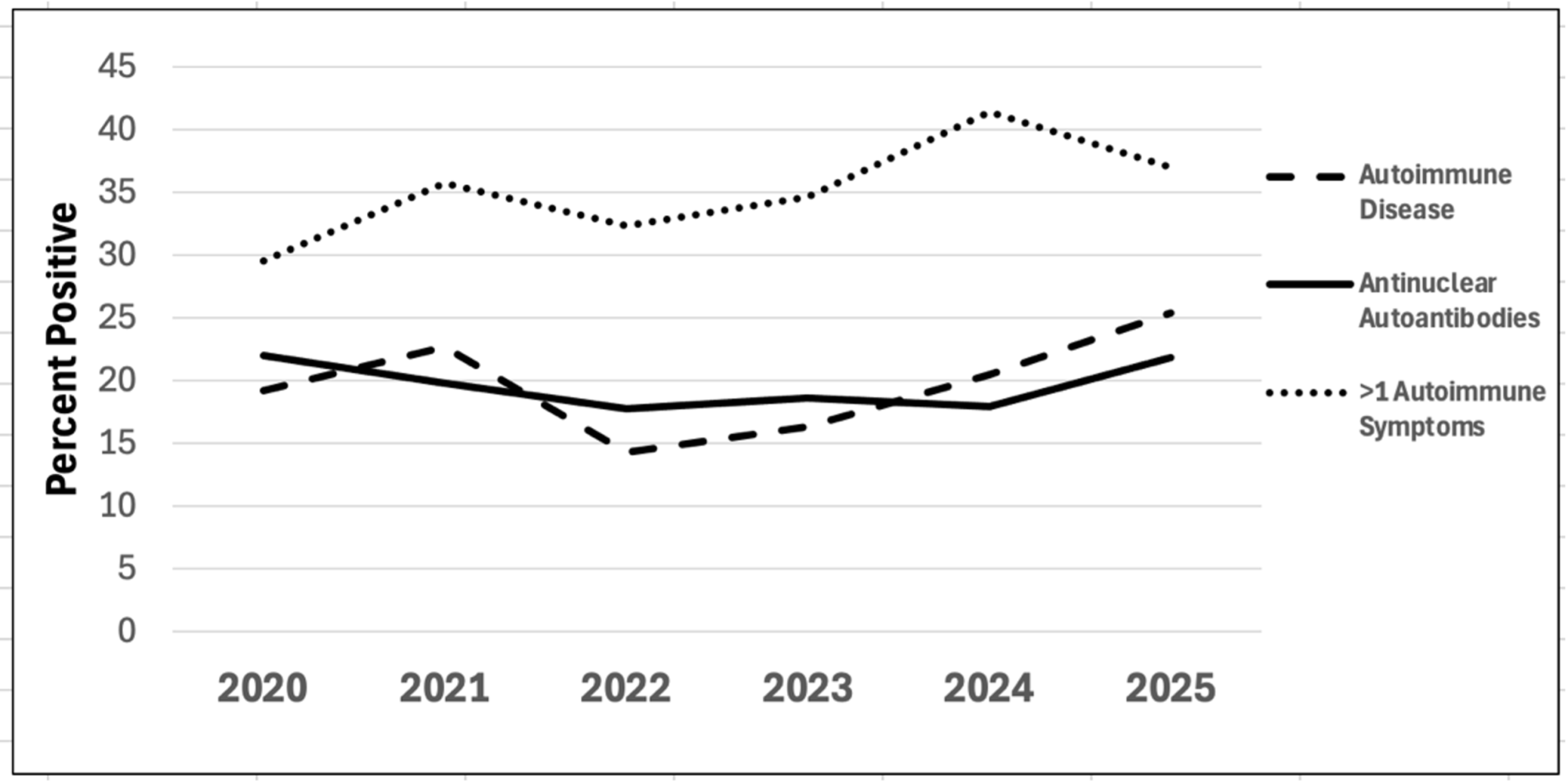

Since the vermiculite mine in Libby closed in the 1990s, most exposures to LA have been legacy exposures. The Center for Asbestos Related Disease (CARD) is tasked by its funding agency (11) with ongoing health screening of LA-exposed individuals for asbestos-related diseases, including autoimmune diseases. Given that autoimmune diseases (AID) often have a long latency between exposure and disease, it seemed worthwhile to tabulate data over the last several years to determine whether the frequency (prevalence) of AID has been dropping. Figure 1 illustrates that the frequency of AID among LA-exposed screening participants remains very high, compared to the expected U.S. prevalence of AID, which is approximately 4.6%. (12)

The immune system plays a profound role in directing the outcomes of exposure, including cytokine shifts and development of autoantibodies, which can result in AID, development of fibrosis, and impairment of the body’s ability to fight cancer. These diseases are difficult to treat, so the best approach is prevention, and the best prevention is exposure reduction. Physicians, public health officials, and researchers must evaluate exposed populations and individuals for AID and raise awareness that legacy asbestos remains a serious health risk around the world.

References

- Pfau, J. 2024, https://doi.org/10.56367/OAG-041-11247

- Morrissette, L. 2024, https://doi.org/10.56367/OAG-042-11274

- Pfau, J., et al. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2024.103603

- Noonan, C.W., 2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm.2017.03.74

- Buck, B., et al., 2013. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2013.05.0183

- Pfau, J., et al., 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2017.08.022

- ADAO, 2022. https://www.asbestosdiseaseawareness.org/newsroom/blogs/adao-release-epa-makes-a-good-start-but-must-do-more-to-combat-the-serious-health-risks-of-legacy-asbestos/

- Burki, T., 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(24)00155-4

- EPA, 2024. https://www.epa.gov/chemicals-under-tsca/epa-issues-draft-part-2-risk-evaluation-asbestos-public-comment

- EPA-740-R-24-006, 2024. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-11/01.-asbestos-part-2-.-risk-evaluation-.-public-release-.-hero-.-nov-2024.pdf

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR).

- Abend, A.H., et al. 2024. https://www.jci.org/articles/view/178722

- Diegel, R., et al., 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/15287394.2018.1485124