Dr Yves R. Sagaert emphasizes the importance of organizations shifting away from traditional static budgeting, which relies on historical trends. He advocates adopting predictive AI and advanced forecasting as essential strategic tools for both governments and businesses to proactively adapt to uncertainties in their environments

The era of radical uncertainty

Europe is on the cusp of an era of increasing complexity. From disrupted supply chains and energy transitions to shifting geopolitical plates, the days of linear stability are behind us. In today’s volatile setting, where limited fiscal room is squeezed by heavy debt payments and changing demographics, a conventional, static budget based only on historical trends traps organisations in a constant state of reactive crisis response. In the Belgium Forecast Society (BELFORS), we believe that predictive AI and advanced forecasting should no longer be seen as niche technical tools, but as core strategic capabilities that enable governments and businesses to model future scenarios and shift toward proactive, resilient planning and optimization. Governments frequently encounter substantial challenges in implementing countercyclical fiscal policies, such as increasing public expenditure during economic downturns. At present, public debt levels have reached historical highs in many countries, thereby constraining their fiscal space and diminishing their capacity to absorb future macroeconomic shocks. This reduced resilience is particularly problematic in a context characterized by accelerating climate change, large-scale interstate conflicts, and increasingly volatile and unpredictable trade policies.

Advanced forecasting replaces these deterministic models with stochastic frameworks, allowing institutions to budget more resiliently. For policymakers, the application is one of fiduciary oversight. Predictive models enable a shift from reactive measures to dynamic resource planning, ensuring that public funds track emerging exigencies rather than trailing them. By simulating regulatory interventions within a digital twin of the economy, policymakers can model counterfactuals-assessing potential market distortions or distributional effects before legislation is enacted, moving from a heuristic exercise to an empirical discipline, minimizing the gap between legislative intent and economic reality.

High-stakes forecasting projects can successfully drive digital transformation by creating an immediate, concrete need for integrated, high-quality data. This model-driven pressure breaks down data silos, improves data architecture, and accelerates decision- making. As the benefits become visible, people are more motivated to maintain structured, high-quality data over time, raising overall digital maturity with forecasting as a catalyst.

Theory put into practice: the asymmetric risks in perishable forecasting

The theoretical benefits of predictive AI are best illustrated through the harsh constraints of the perishable goods sector. A recent research initiative in Flanders, called Smart Meal Planning (SMP), brought together school caterers, distributors, and hospitals to address a specific, high-stakes variable: the volatility of demand for ready-to-eat meals. The project was partially funded by the Flanders innovation & entrepreneurship (VLAIO) and was a close collaboration between KU Leuven and VIVES University of Applied Sciences.

This sector presents a unique challenge of asymmetric risk. In standard retail environments, the cost of forecasting error is mitigated by shelf life: an overestimation of prepacked cookies merely results in a temporary increase in holding costs. In the context of heated ready-to-eat meals, however, the error term is asymmetric and is immediately penalized. Over- forecasting results not in inventory, but in immediate waste: what is not consumed today is discarded tomorrow. Under-forecasting results in service failure for vulnerable populations.

The SMP architecture consists of a three-stage modelling framework that uses gradient boosting to enable computationally efficient learning in high-dimensional feature spaces. In the first stage, adaptive feature selection is employed to dynamically filter input variables with the objective of maximizing the signal-to-noise ratio and aligning the effective feature space with the statistical properties and volume of the available data. In the second stage, temporal feature engineering is conducted, in which autoregressive terms (lagged variables) and rolling- window summary statistics are constructed to capture latent seasonal patterns and trend dynamics in the underlying time series. In the third stage, structural regularization is applied by tuning tree-complexity hyperparameters, such as maximum depth and leaf-wise growth constraints, to appropriately manage the bias- variance trade-off, thereby promoting robust generalization performance and mitigating overfitting to idiosyncratic historical noise.

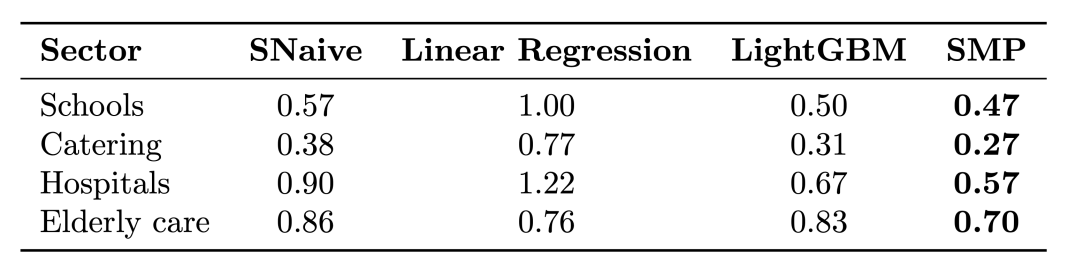

Table 1 reports the Root Mean Squared Scaled Error (RMSSE), a forecast error metric chosen for robustness across different operation sizes and stability with zero demand. RMSSE penalizes large errors and compares performance against a naive historical-level baseline: values below 1.0 indicate that the forecasting method outperforms this simple baseline.

The study benchmarks four distinct modelling approaches across four operational sectors. The seasonal naive model forecasts by repeating last season’s corresponding value, serving as a simple, cost-free seasonal baseline that more advanced methods should surpass. Two advanced Machine- Learning benchmarks are used: a linear regression model and a nonlinear LightGBM model, both using exogenous variables and engineered features.

The proposed methodology (SMP) consistently outperforms these benchmarks, yielding 6-15% performance improvement over the best-performing reference model and up to 37% when looking back to the last period. Considering that these firms supply hundreds of schools, each serving hundreds of children, this practice results in a substantial reduction in the volume of meals being discarded as food waste.

Looking forward with leading Intelligence

A single-point forecast is almost invariably wrong: the strategic question is by how much. An alternative way of looking at a forecast is using a probability distribution, as a ‘cone of uncertainty’ that widens as the time horizon expands. A narrow distribution will tend to provide more certain forecasts, while wide distributions will allow for anticipative measures.

In an economy that shifts from being globally interconnected to globally decoupled, there is a need to look outward. To build resilience, organisations can integrate leading indicators: exogenous variables that act as an early warning system (Sagaert & Kourentzes, 2025). If a leading indicator suggests a disruption in the tire supply chain six months out, a manufacturer can adjust procurement immediately, long before the shortage hits the factory floor (Sagaert et al., 2018).

The adoption of predictive AI is not a technocratic exercise; it is a fundamental component of European competitiveness (Draghi, 2024). As the continent navigates the twin transitions of decarbonization and digitalization, the margin for error narrows. A Europe that embraces this capability is a Europe that masters its own timeline. The Belgium Forecast Society (BELFORS) wants to contribute to these challenges as a leading European research centre.

References

- Draghi, M. (2024). The Future of European Competitiveness – A Competitiveness Strategy for Europe. European Commission.

- Sagaert, Y. R., Aghezzaf, E. H., Kourentzes, N., & Desmet, B. (2018). Temporal big data for tactical sales forecasting in the tire industry. Interfaces, 48(2), 121-129.

- Sagaert, Y. R., & Kourentzes, N. (2025). Inventory management with leading indicator augmented hierarchical forecasts. Omega, 136, 103335.