Rethinking slavery at the Cape: Although slavery was common, the Cape was not a ‘slave economy’ in the strict sense, as it did not rely solely on slavery for economic surplus, according to Lund University’s Professor Erik Green

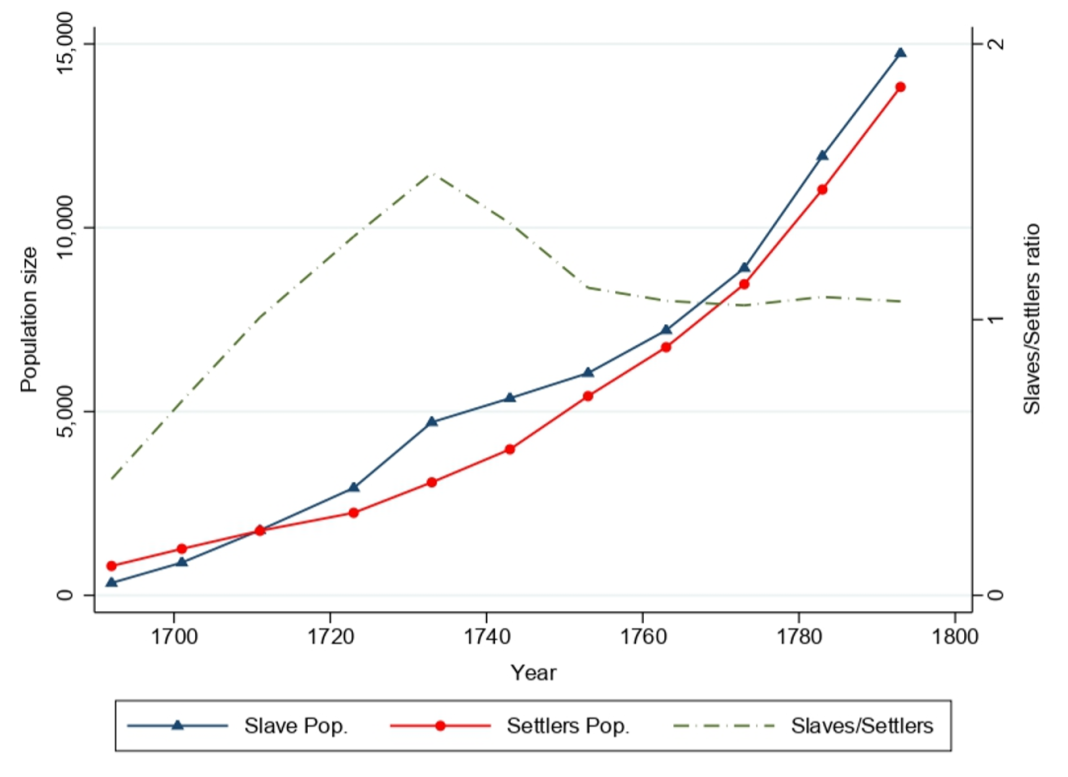

Following the establishment of its trading post at the Cape, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) quickly began importing enslaved individuals. By 1705, approximately 85% of farmers in Stellenbosch – the center of crop farming at the Cape – enslaved people. Numerous scholars have argued that enslaved labor was central to the expansion of European settlement in the region (see Green 2022 for an overview). Slave labor enabled settlers to establish profitable farms by exploiting imported human capital. As illustrated in Figure 1, the enslaved soon outnumbered the European settlers.

There is little doubt about the significance of slavery in Cape society. The legal and social right to own human beings was deeply embedded in the colony’s cultural, social, and political fabric. However, the mere presence and widespread use of slavery does not necessarily mean that the Cape Colony constituted a ‘slave economy’ in a strict economic sense. A slave economy is typically defined as one in which slavery plays a central role in generating economic surplus.

Historical data on the enslaved at the Cape is limited. They only appear as numbers in a column in the tax censuses (Opgaafrolle), which constitute the key historical sources used in the Cape of Good Hope research project (www.capepanel.org). Having said that, the transcription of the censuses allows us to further investigate the economic role of slavery at the Cape and hence contribute to the larger literature on the emergence and persistence of labour coercion.

Economic role of slavery

In earlier work, I have questioned the profitability of slave labor in the Cape agricultural economy (Green, 2014; 2022). Enslaved individuals were expensive, with limited data suggesting that the cost of purchasing a single enslaved person was roughly equivalent to the average annual income of a European farmer. While earlier studies (e.g., Worden 1985) posited that slave productivity at the Cape matched that of plantation economies in the Caribbean and the American South, more recent research drawing on detailed historical sources (Fourie & Green, 2015) indicates that productivity levels were comparatively modest.

This raises an important question: why did settlers continue to use slave labor despite its seemingly limited economic returns? Part of the answer lies in pure economics. Slavery often persisted for reasons related to social status and political power, long after it ceased to make economic sense. Nonetheless, in a context such as the Cape – where average settler wealth was significantly lower than in the New World—slavery’s persistence likely required some form of economic utility. To understand this dynamic, it is essential to consider that enslaved individuals were not only a source of labor but also served as a means to access capital.

Slavery and access to capital

Settler-farmers at the Cape faced not only labor shortages but also severe capital constraints. The formal credit market was limited and largely controlled by a small number of institutional actors, including the VOC, the Orphan Chamber, churches, and a few companies. These entities accounted for only a small fraction of lending activity. In fact, 90% of lending transactions in the eighteenth-century Cape were carried out by private individuals, mostly settlers.

Access to credit requires collateral. Although land was theoretically a valuable asset, most settlers did not own the land they cultivated and were thus unable to use it as security. They did, however, possess one asset over which they held full legal ownership: enslaved people. Unlike land, which was immobile and tied to uncertain future yields, enslaved individuals were mobile and could be sold in markets offering the most favorable conditions. In the context of capital scarcity typical of frontier economies, this made slave ownership highly correlated with indebtedness. Enslavers regularly pledged their human property as collateral to secure loans for investment, land acquisition, business ventures, consumption, and agricultural production.

Recent research by Martins (2021) and Green and Martins (forthcoming) demonstrates that the use of enslaved individuals as collateral was fundamental to the survival and profitability of European settler farms at the Cape. These findings are significant for several reasons. First, they underscore that slavery was qualitatively different from other forms of coerced labor, such as serfdom or indentured servitude. Slavery granted the enslaver absolute property rights over another human being, enabling not only labor extraction but also access to capital markets.

Equally important, this research highlights the unique and brutal nature of slavery at the Cape. Enslaved individuals were subjected to exploitation in ways unparalleled in other systems of coerced labor. Stripped of all legal rights and human dignity, they were effectively transformed into economic assets. As Orlando Patterson (1982) has famously argued, the enslaved were rendered ‘socially dead.’

The wealth generated by European settlers at the Cape would not have reached the same scale without the dual economic roles played by the enslaved, as both laborers and capital. Thus, the early economic history of South Africa is inextricably tied to systems of coercion and exploitation.

References

- Green E. (2014) ‘The economics of slavery in 18th century Cape Colony – Revising the Nieboer-Domar hypothesis’, International Review of Social History 59(1): 39-70

- Fourie J. and E. Green (2015) ‘The missing people – Accounting for indigenous populations in Cape colonial history’ Journal of African History, 50(2): 195-215

- Green, Erik (2022). Creating the Cape Colony: The political economy of settler colonialization. Bloomsbury Academic

- Martins, I. & Green, E. (forthcoming) ‘Capital and labor: Theoretical foundations of the economics of slavery. Journal of Global History.