Written as part of the LIFE-FRESHMAN project, this article examines the issue of coastal groundwater salinization in the EU, particularly its impact on freshwater reserves, and highlights key strategies for mitigation

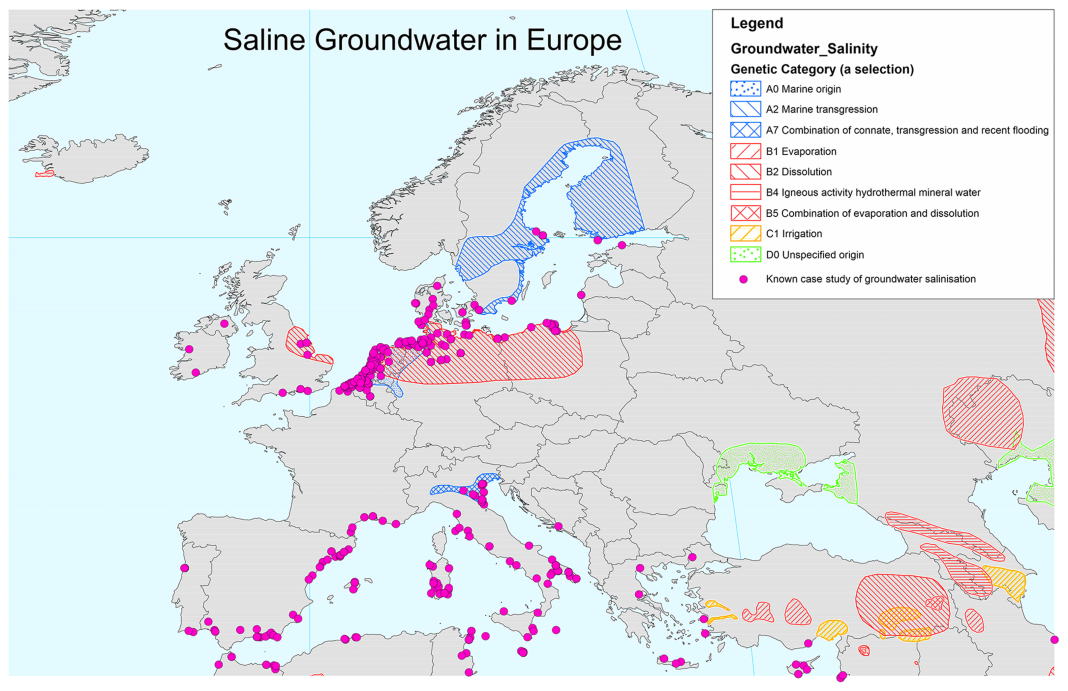

Coastal zones across Europe rely on fresh groundwater reserves for drinking water production, agriculture, and industry. In the mid to high-latitude regions, freshwater use is primarily urban and industrial, whereas irrigation and tourism dominate seasonal water demand in the Mediterranean area (Custodio, 2009). These fresh groundwater reserves depend on rainfall or additional artificial recharge using local fresh surface water resources, such as rivers and lakes (MAR; managed aquifer recharge). Overexploitation of coastal groundwater results in the salinization of these aquifers (Figure 1; Van de Wal et al., 2024), often leading to the abandonment of groundwater extraction wells. As coastal urban areas continue to experience rapid population growth and economic development, freshwater demands are only increasing (Vörösmarty et al., 2000). Meanwhile, saltwater intrusion is further amplified by climate change through changes in natural recharge patterns and sea-level rise (Portmann et al., 2013; Zamrsky et al., 2024).

Coastal groundwater salinization is a global issue that poses a threat to the sustainable development of coastal zones. Alternative sources of freshwater may be available, but these are also under pressure. For example, rivers and lakes may also suffer from droughts and salinization due to climate change and overexploitation, or from pollution resulting from insufficient wastewater treatment (EEA, 2024). Protecting coastal groundwaters by mitigating salinization is thus of great importance for coastal freshwater management and for safeguarding freshwater supply.

How to mitigate groundwater salinization

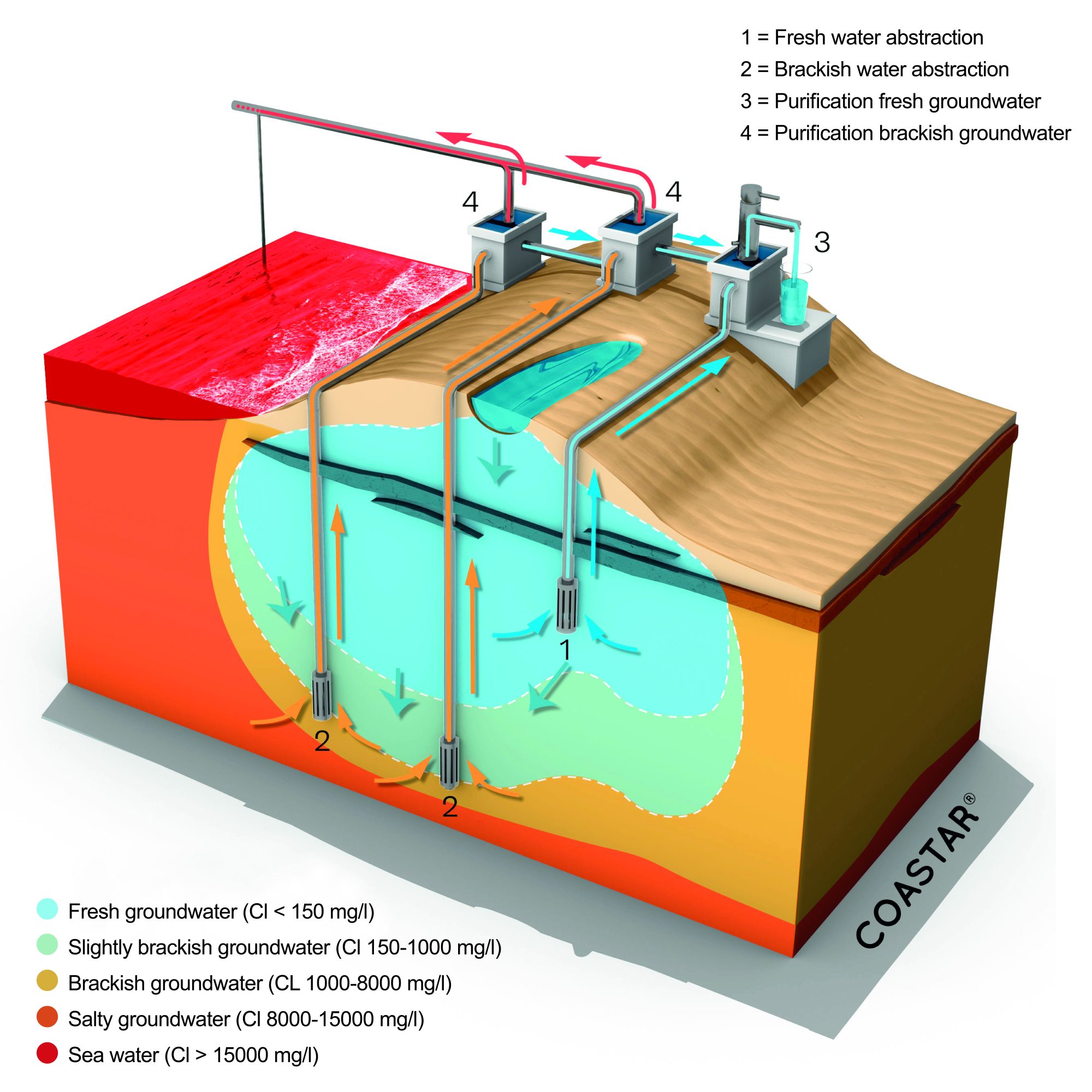

Coastal groundwater salinization occurs when the water levels (hydraulic heads) in the aquifer are lower than sea level and/or lower than the underlying saline groundwater. Various strategies can be implemented to maintain a seaward hydraulic gradient, providing a hydraulic barrier against seawater intrusion (e.g., Hussain et al., 2019; Maliva, 2020; Missimer and Maliva, 2025). Besides reduction and relocation of freshwater pumping, possible measures include artificial recharge (positive hydraulic barriers), pumping of brackish or saline groundwater from the aquifer (negative hydraulic barriers), and a combination of techniques (mixed barriers). Each of these approaches has its own advantages and limitations in terms of practical operation and control of seawater intrusion (Hussain et al., 2019, Missimer and Maliva, 2025).

The fresh groundwater reserves in the Dutch coastal dunes have been intensively exploited for drinking water production since the nineteenth century (Stuyfzand, 1993). As freshwater demands gradually increased, reserves reduced, and extraction wells salinized. Since the 1950s, drinking water utilities have recharged pre-treated river water from the Meuse and Rhine rivers through infiltration ponds to recover the coastal aquifers from overexploitation. This approach is now used to sustain the freshwater volume stored in the coastal groundwater system and to prevent future salinization of groundwater extraction wells.

Another good example of a positive hydraulic barrier in Europe is in Barcelona, Spain. The principal aquifer of the Llobregat Delta has been affected by seawater intrusion since the 1960s. By order of the Catalan Water Agency, 14 injection wells were installed to halt seawater intrusion (Ortuño et al., 2010). Reclaimed water from the wastewater treatment plant of Baix Llobregat is highly purified and used for injection.

Good examples of negative hydraulic barriers are also installed in Spain and the Netherlands. Since 2006, saline groundwater has been extracted with multiple beach wells from below a freshwater lens in Almería (Spain) to have an additional source of freshwater by desalination. This extraction has successfully reduced the risk of seawater intrusion and freshened the aquifer (Stein et al., 2020). Similar conclusions were drawn at the LIFE Freshman pilot in the coastal dunes of the Netherlands, where brackish groundwater was extracted between 2022 and 2025 for desalination purposes and to reduce the risk of groundwater salinization (Zwolsman, 2025; Hendrikx et al. 2025). The most efficient operation of a saltwater interception well is near freshwater extraction wells, to prevent the upconing of saline groundwater and the salinization of the freshwater. This ‘Freshkeeper’ strategy has been successfully applied at Noardburgum, the Netherlands, to reactivate a previously abandoned well field (Zuurbier et al., 2017).

Conclusion

Groundwater salinization is a problem across the EU, threatening the water supply to the public, agriculture, and industry. Artificial recharge (‘positive hydraulic barrier’) and dedicated saline groundwater extraction (‘negative hydraulic barrier’) have been demonstrated as successful mitigation strategies against groundwater salinization in the Netherlands and Spain. Examples like these can help guide the sustainable development of Europe’s coastal zones, and contribute to the recently adopted European Water Resilience Strategy (EC, 2025).

CLICK HERE for references