Professor Helen Fulton at the University of Bristol, examines the case study of the Medieval March of Wales, a vibrant multicultural border region between Wales and England, to explore spatial identities which challenge modern ‘nation-state’ nationalisms

Social histories are traditionally nationalist, focusing on the cultural production of modern nation-states and typically showcasing the outputs of a single dominant language.

This nationalist approach to social history means that very often the experiences of multilingualism, border cultures, and substate nations are routinely elided.

MOWLIT, ‘Mapping the March: Medieval Wales and England, c. 1282–1550’

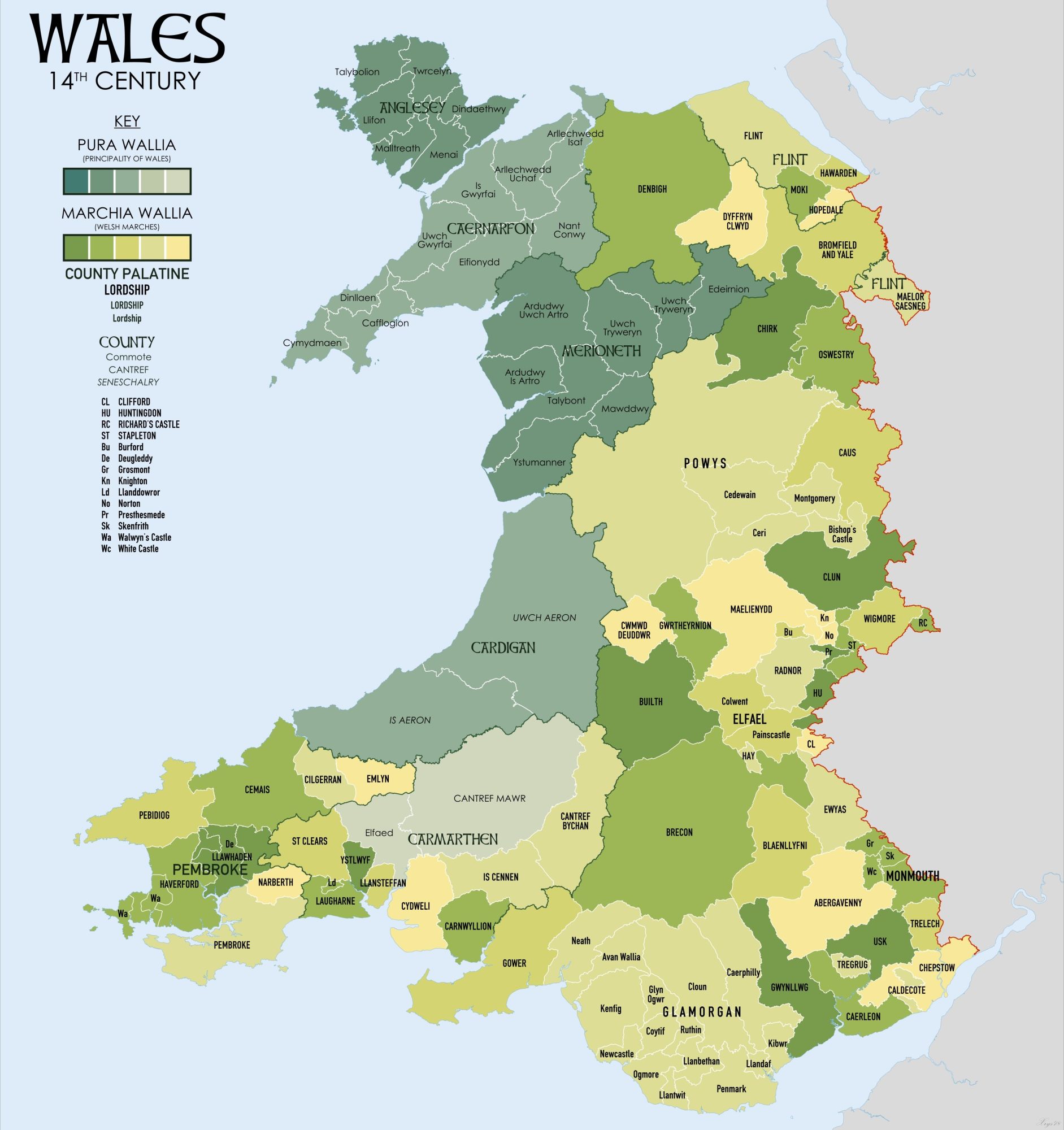

Our research project, MOWLIT, ‘Mapping the March: Medieval Wales and England, c. 1282–1550’, uses the case study of the medieval March of Wales, a vibrant multicultural border region between Wales and England, to examine spatial identities which challenge modern ‘nation-state’ nationalisms.

Wales in the late Middle Ages was a deeply divided nation, split between Crown and Marcher lordships, between Welsh and English cultures and languages, and between Welsh gentry and English nobles who exercised colonial rule within their lordships.

Yet many of the Welsh demonstrated significant loyalty to their English lords, expressed through military and administrative service, intermarriage, and praise poetry. In the late fourteenth century, the rebel Owain Glyn Dŵr, like many of his fellow Marcher gentry, served Richard II as a loyal military commander both in France and the Scottish wars.

Welsh poetry research and the English link

Welsh praise poets composed poetry for both Welsh patrons and English noblemen. In the late fourteenth century, Iolo Goch famously composed a poem in Welsh to his English Marcher lord, Sir Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March, who was born at Usk in 1374 and was killed in Ireland in 1398.

For Iolo Goch, Sir Roger represented the best aspects of Marcher lordship in Wales and the kind of leadership so evidently lacking in the king (Richard II) at that time. The main theme of the poem is Sir Roger’s military record and his destiny to defeat the Irish, a theme that is announced at the beginning of the poem:

Syr Rosier asur aesawr, Syr Rosier o’r Mortmer mawr, Rosier ieuanc, planc plymlwyd, Sarff aer o hil Syr Raff wyd, Rhos arglwydd, Rosier eurglaer, Rhyswr, cwncwerwr can caer. (Johnston 1993, no. 20)

Sir Roger of the azure shield, Sir Roger of great Mortimer, young Roger, plank of battle, you are a warlike serpent of Sir Ralph’s line ,lord of Rhos, golden bright Roger, hero, conqueror of a hundred forts. (Johnston 1993)

Sir Roger’s Englishness is acceptable mainly because he is a Marcher lord and, therefore, invested in Wales as well as England. But as the poem goes on to say, it is Roger’s Welsh descent that is of prime importance. His ancestor, Sir Ralph Mortimer (c. 1195–1246), had married Gwladus Ddu, the daughter of one of the great princes of Wales, Llywelyn ab Iorwerth or Llywelyn the Great (c. 1173–1240), king of Gwynedd and ruler over the whole of Wales. Iolo is, therefore, praising Roger as a Marcher lord and member of the English aristocracy while also reminding him of his Welsh heritage.

Welsh-language literature in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries

The kind of double-think expressed by Iolo Goch is typical of Welsh-language literature in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, where an acknowledgement of England’s ownership of Wales, and even some pride in the resident aristocracy represented by the Marcher lords, is tempered by an ongoing resentment of England’s colonialist attitudes.

A deep vein of anti-English feeling permeates Welsh literature of the period, with the English of England and the Marches routinely belittled. [Fulton 2008: 194.] The Welsh poet Hywel Dafi (fl. 1450-80) advises his patron, Harri ap Mil of Gwent (probably of Norman extraction), to choose a Welsh rather than an English wife:

Cymer ferch Cymro farchawg Aur i gyd ei war a’i gawg. Cais ferch addfain ugeinmlwydd Ac na chais ferch Sais o’r swydd. (Lake 2015, no. 65)

Take the daughter of a Welsh knight, his tableware and basins all of gold. Find a slender girl of twenty years, and don’t get an English girl from the county. [My translation]

However, such advice was seldom heeded. Intermarriage in both directions, an important strategy of colonisation from the time of the Norman conquest of the March, became increasingly common in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, leading to complex social identities based more on class and language than on the kind of nationalism associated with modern nation states.

Welsh and English joining Forces

Welsh and English often joined forces against common enemies, as they did during the Glyn Dŵr rebellion against the English king Henry IV from 1400 to 1410. Among the rebel faction, Owain’s most significant supporters were English noblemen, the Earl of Northumberland and Edmund Mortimer. At the same time, many Welsh people resisted Owain’s rebellion and remained loyal to the English crown.

Our study of the people, places, and manuscripts circulating in the medieval March of Wales shows that social identities were far more complex than nationalist models allow. Factors such as language, culture, ancestry, and legal status were far more important than nationhood in constructing a distinctive Marcher identity within a colonial society.

We welcome comments and queries from academics, policy makers, local historians, and members of the public – you can get in touch with us by emailing: mapping-the-march@bristol.ac.uk

References

- Fulton, Helen. 2008. ‘Class and Nation: Defining the English in Late-Medieval Welsh Poetry’, in Authority and Subjugation in Writing of Medieval Wales, ed. R. Kennedy and S. Meecham-Jones. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 191–212

- Johnston, Dafydd, ed. and trans. 1993. Iolo Goch: Poems. Llandysul: Gwasg Gomer.

- Lake, A. Cynfael, ed. 2015. Gwaith Hywel Dafi, II. Aberystwyth: Canolfan Uwchefrydiau Cymreig a Cheltaidd Prifysgol Cymru.