This Soil Science Challenge project was funded by the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (DAFF). It addressed fundamental processes associated with the impacts of biological amendments, including waste-derived amendments, on soil biological processes that underpin soil health and agricultural sustainability.

The experiments conducted sought to contribute an in-depth understanding of complex soil processes, which involve soil physical, chemical, biological and hydrological interactions and lead to enduring soil fertility in agricultural systems.

Background

This Soil Science Challenge project was funded by the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (DAFF). It addressed fundamental processes associated with the impacts of biological amendments, including waste-derived amendments, on soil biological processes that underpin soil health and agricultural sustainability. The experiments conducted sought to contribute an in-depth understanding of complex soil processes, which involve soil physical, chemical, biological and hydrological interactions and lead to enduring soil fertility in agricultural systems. The co-application of biological amendments with fertilisers was investigated in field experiments, as well as in complementary glasshouse experiments. Biological resources, including those derived from waste organic materials, were expected to contribute benefits beyond those achieved through the use of chemical fertilisers alone.

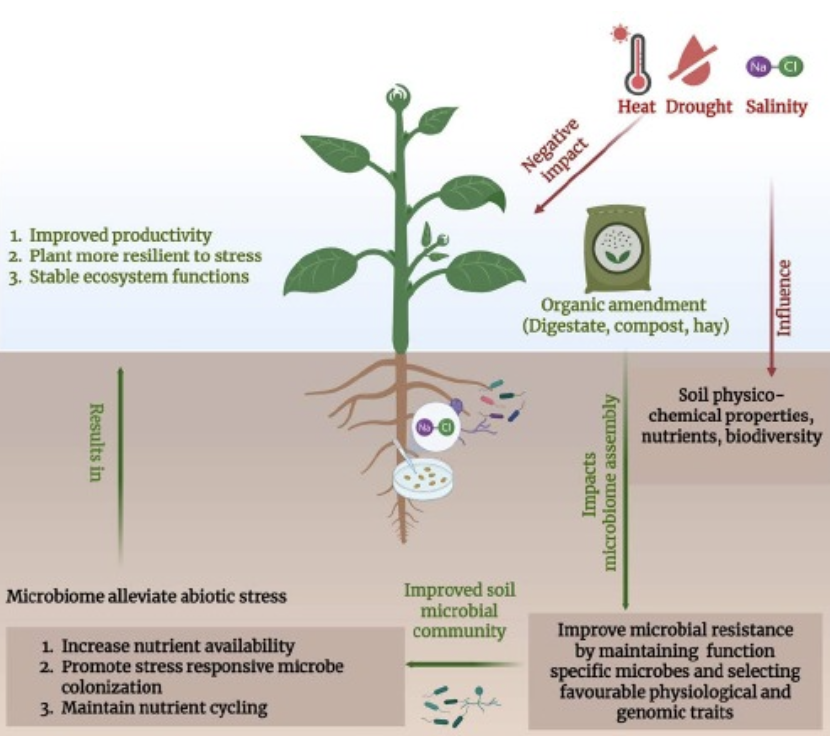

The project used an interdisciplinary approach to (1) quantify the enhancement of biological products on soil biology and nutrient cycling and identify the mode of action and mechanisms involved, including when used in combination with chemical fertilisers, (2) develop molecular indicator(s) of soil health that measure soil functionality at different scales (locally, regionally, nationally) and integrate them into more informative soil-health indices tools, and (3) assess the extent to which biological amendments can mitigate the negative and increasingly severe effects of seasonal drought conditions on plant growth and biological nutrient cycling.

Field-based studies investigated structural and functional attributes of soil biota, including key indicator species of soil health across spatial and temporal scales.

Glasshouse experiments sought to narrow down which biological amendments are best suited to enhancing soil resilience to stress under changing climatic conditions that include more wet-dry periods and drought stress, and non-wetting soils.

Laboratory analyses aimed to identify the optimal combinations of biological amendments to complement mineral fertiliser and soil conditioners, enhancing nutrient cycling and sequestering carbon without negatively impacting yield.

Data on soil biology enhancement was used to re-calibrate and expand existing models and to identify systematic and predictable patterns for guidance on economic application of specific amendments to soils.

This project addressed the Australian National Soil Strategy Goal 1 ‘Prioritise soil health’ by improving Australia’s international leadership in soil science, awareness and management, and identifying sustainable agricultural farming practices that maintain productivity and profitability, and Goal 3 ‘Strengthen soil knowledge and capability’. The research was funded by the DAFF Soil Science Challenge Program.

The research was conducted under the following 6 parts:

- Part 1:

- Mechanisms underpinning the impacts of biological amendments on relative contributions of bacteria and fungi to carbon and nutrient (N and P) cycling

- Part 2:

- Baseline investigation of soil bacterial and fungal responses to nutrient sources derived from waste technologies as complements to chemical fertilisers

- Part 3:

- Impact of biological amendments on microbial diversity across soil types, land use and environmental conditions

- Part 4:

- Impact of biological amendments on microbial diversity across soil types, land use and environmental conditions

- Part 5:

- Impacts of biological amendments on soil carbon dynamics and effects on microhabitats for soil biology

- Part 6:

- Modelling of carbon from bacterial and fungal responses to co-application of biological and chemical amendments to soil and the economic and environmental benefits

Part 1: Mechanisms underpinning the impacts of biological amendments on relative contributions of bacteria and fungi to carbon and nutrient (N and P) cycling

This part of the project investigated key mechanisms behind the impacts of biological amendments on plant and soil microbiomes, and how soil organisms impact plant productivity and yield by improving nutrient availability in soil. Experiments were conducted in controlled soil microcosms, glasshouse experiments and in field trials.

Investigations used a range of soil amendments, including clays, composts, biochar, digestate, struvite, hay, fertilizers and their combinations. Experiments explored how soil amendments impacted microbial biomass, the relative abundance of bacteria and fungi, and the microbial community structure in association with nutrient pathways. For example, experiments related to clay, organic based soil amendments and fertilisers revealed how bacterial communities were very responsive to organic amendments while fungal communities were more stable. Application of cereal straw significantly increased soil macroaggregate formation, thereby improving the soil structure. The combination of cereal straw, clay and chemical fertiliser increased the abundance of microbial genes involved in carbon and nitrogen cycling. In this case, the organic amendment was the primary driver of microbial responses and nutrient cycling gene abundance, whereas clay acted as a stabilizing agent. Soil applications of biological amendments with fertilisers enhanced these impacts compared to use of fertiliser alone.

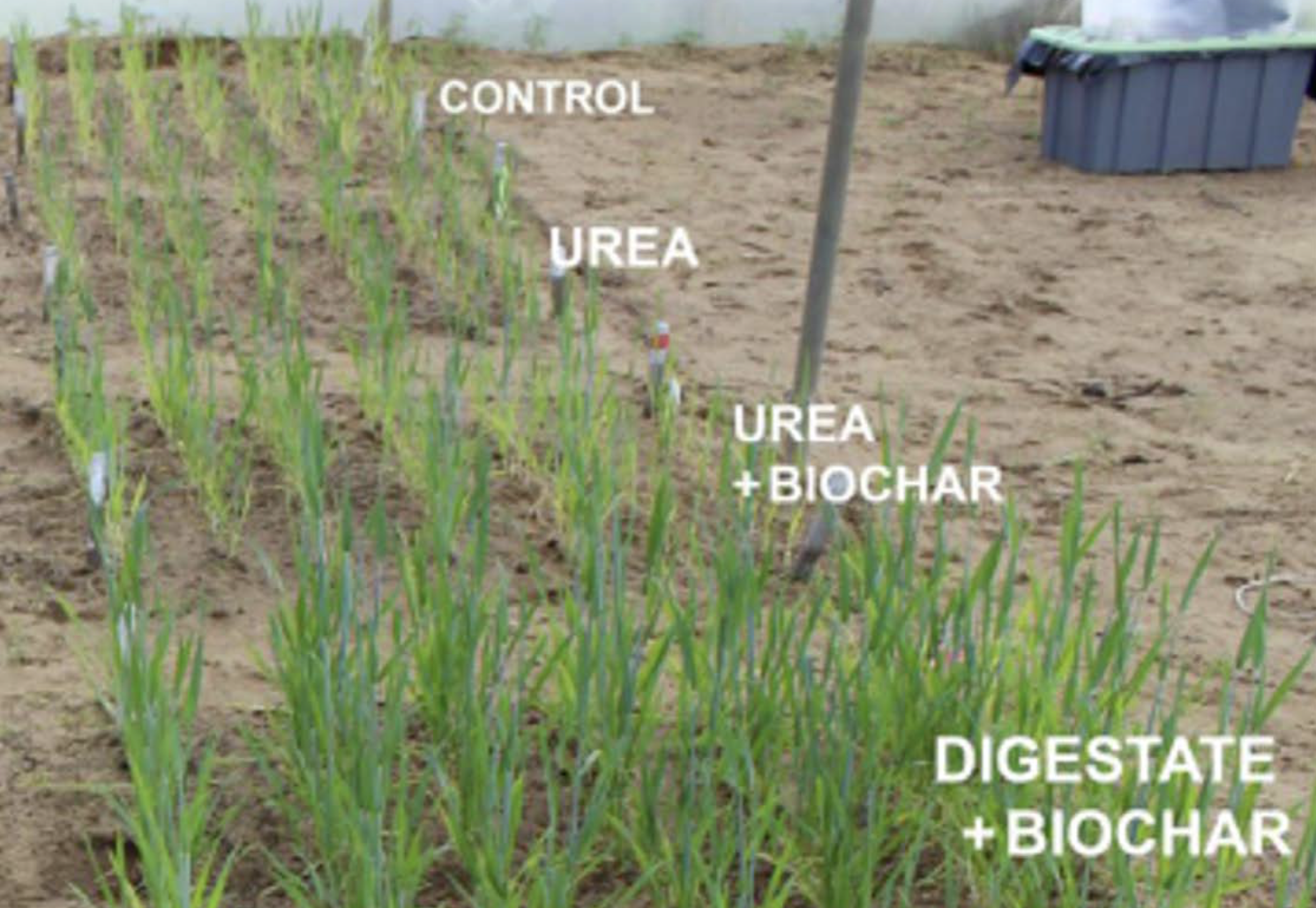

In a wheat field trial, digestate-loaded biochar (an engineered slow-release organic nitrogen amendment) significantly improved yields compared to either urea or a urea-loaded biochar under both normal rainfall and drought conditions. Under constrained moisture conditions, digestate-loaded biochar improved plant nitrogen uptake. A key microbial mechanism involved was improved resistance of the root bacterial community exposed to digestate loaded biochar. This reflected enhanced capacity of the root microbiome to maintain essential functions despite stress. Furthermore, the bacterial resistance index was correlated with the abundance of families of bacteria which had drought- responsive and plant growth-promoting characteristics. This showed that under water-stress, digestate-loaded biochar treatment supported beneficial microbial enrichment at harvest, with potential for enhancing plant stress tolerance.

Another study investigated the potential of organic amendments to alleviate abiotic stress in a controlled environment system with a C3 plant (annual ryegrass) and C4 plant (Rhodes grass). These two pasture grasses differ in their photosynthetic pathways and in their efficiencies under different environmental conditions. Ryegrass is a winter-active grass and Rhodes grass is a summer active grass. Plants were grown at both moderate (day/night 25ºC/15 ºC) and high (day/night 30ºC/20 ºC) temperature. At the higher temperature, there was greater nutrient mobilisation when organic matter was applied to the soil, indirectly alleviating heat stress in the plants. With application of the organic residues, the bacterial and fungal communities responded differently. The bacterial resistance index of the plant microbial community improved for both the C3 and the C4 grass, whereas fungal resistance only increased in association with the C4 grass. Application of the organic residues to this soil also promoted root colonisation by heat-tolerant microbes.

Part 2: Baseline investigation of soil bacterial and fungal responses to nutrient sources derived from waste technologies as complements to chemical fertilisers

This part of the project focused on soil bacterial and fungal community responses to nutrients derived from food waste sources such as digestate. An overarching aim was to evaluate the potential use of waste-derived fertilisers as a supplement to chemical fertilisers. This was investigated using a series of glasshouse experiments and a field trial.

The glasshouse experiments used ryegrass to evaluate the optimal rate of application of an organic amendment in the form of digestate-loaded biochar and its potential to mitigate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions when compared to chemical fertiliser. Further, it assessed how soil pH could affect the GHG emissions, with addition of lime to soil. The incorporation of digestate sought to bind more nitrogen to the biochar. The digestate loaded biochar reduced nitrous oxide (N20) emission by 75 % in comparison to solid digestate. This response was accompanied by a decrease in the bacterial dentrifier genus Dokdonella, and a decrease in the abundance of the gene nirK. Liming further lowered N20 emissions and the N20-consuming gene nosZII.

Digestate loaded biochar improved nitrogen uptake compared to solid digestate, showing the potential for the digestate amended with biochar to increase nitrogen availability for ryegrass. In another experiment using ryegrass, the optimal rate of application of digestate loaded biochar was assessed in terms of improving soil health and plant productivity combined with lowered GHG emission. Digestate loaded biochar applied at the equivalent of 150 kg nitrogen per hectare improved soil health and reduced carbon dioxide (CO2) emission, although N2O emission remaining unaffected and methane (CH4) emission increased. This lack of change in N2O emission was associated with an enrichment of the denitrifier genus Dokdonella as well as genes involved in N2O consumption. Digestate loaded biochar increased fungal diversity in the rhizosphere and colonisation of roots by plant growth promoting bacteria.

Overall, these studies highlighted the potential for food waste derived digestate loaded biochar to be used to strip nutrients from digestate and create a slow nitrogen releasing organic fertiliser, with potential to increase soil health and reduce GHG emissions. This was validated under field conditions where digestate loaded biochar increased wheat yield when irrigated and in drought conditions. In this study, it promoted colonisation of roots by beneficial microbes, and enhanced nitrogen uptake in shoots in the sandy soil where the treatments were applied. These experiments contributed to understanding the potential for biological amendments to complement synthetic fertilizer, in support of circular economy principles and sustainable agricultural practices.

Overall, these studies highlighted the potential for food waste derived digestate loaded biochar to be used to strip nutrients from digestate and create a slow nitrogen releasing organic fertiliser, with potential to increase soil health and reduce GHG emissions. This was validated under field conditions where digestate loaded biochar increased wheat yield when irrigated and in drought conditions. In this study, it promoted colonisation of roots by beneficial microbes, and enhanced nitrogen uptake in shoots in the sandy soil where the treatments were applied. These experiments contributed to understanding the potential for biological amendments to complement synthetic fertilizer, in support of circular economy principles and sustainable agricultural practices.

In a review of the potential use of soil inoculants to further contribute microbial contributions to soil health, issues related to the use of bioinoculants and challenges posed were highlighted, especially in field settings. Priority areas for development of bioinoculants include technical issues such as the need to develop appropriate carriers, the potential for soil and crop specificity of the bioinoculants, and quality control.

Part 3: Impact of biological amendments on microbial diversity across soil types, land use and environmental conditions

This part of the project added depth of investigation on soil biota habitat at the landscape scale. The focus of these investigations was on identifying principles related to use of soil amendments to ameliorate soil constraints and build soil health across the landscape and climate variability. The impacts of different biological amendments were investigated through a nation-wide survey supported by a series of technical reviews, meta-analysis and glasshouse experiments.

Assessment of soil functionality was based on key taxa and functional groups that contribute to ecosystem services across contrasting landscapes and management practices at different spatial (local, regional and national) and temporal scales. Soil biodiversity and functional capabilities were measured by soil DNA sequencing using amplicon for taxonomic diversity and composition of communities of soil bacteria, and soil eukaryotes (including fungi, protists, nematodes), and by shotgun metagenomic sequencing for assessing functional diversity.

In the nationwide survey, soil was sampled from land-use and management regimes for conventional (n=275), organic input (n=65) and non-agricultural (n=68) systems. Soil chemical properties and nutrients were characterised followed by soil biodiversity and functional profiling for all sites. Soil health assessment index of the land-use and management practices showed that organic input practices had a higher soil health index than that for non-agricultural sites, and the conventional farms had a lower soil health index. These differences were attributed to the capacity of the soil to hold moisture under organic management systems. Other soil assessment parameters in included pathogen suppression capabilities, richness of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, and microbial diversity and function profiles.

Reviews of published literature highlighted that low- diversity soil ecosystems can be susceptible to plant pathogen invasion and that practices that improve soil health can enhance pathogen suppression. A diverse and stable soil microbial diversity can increase competition for resources and the potential for suppressing root disease. It was also highlighted that by maintaining a diverse cropping system, there are benefits to both plant and soil health, whereas monocultures have a tendency to allow pathogen build up in soil due to autotoxicity syndrome caused by the presence of the same crop year after year.

Glasshouse experiments were used to investigate the efficacy of several microbial inoculants. In wheat, at seedling stage, a combination of biocontrol agents and a synthetic microbial community (SynCom) reduced disease incidence of Rhizoctonia solani AG8, a fungus which causes bare patch disease, compared to a conventional fungicide treatment. When the SynCom community was combined with a fungicide treatment, yield improved. Another glasshouse experiment showed that SynComs combined with compost reduced disease severity caused by Ralstonia solanacearum in potatoes in comparison to fertiliser which had higher disease severity.