HC Legionella Ltd Authorising Engineer (Water) shares past experiences and outlines what is meant by ‘managing through to resolution’

Following a routine annual sampling regime for a client in line with water safety plan requirements, laboratory data highlighted some concerns that led to a system-wide chlorination. The first set of re-sampling, as per HSG274 Part 2, was undertaken 2 days after the initial disinfection and was successful at delivering the desired systemic not detected results. A second round of confirmation sampling then delivered positive results, which led to further investigation revealing a catalogue of issues that, once resolved, left a “challenging” ward where Legionella continued to prevail. Over the next 24 months, a range of remedial actions were undertaken to resolve the issue, along with monthly sampling, while the “challenging” area was protected by legionella filters. The cost of not doing it right the first time on this site was more than £300,000.

Starting at the start

Challenges were identified on this site during routine samples. This was in line with the site’s Water Safety Guidance plan and using a sampling plan derived from the last round of risk assessments, and in conjunction with BS7592:2008. The routine sampling identified a site wide positive Legionella issue, a significant issue for a healthcare facility due to the immunocompromised population.

There were positives in both the hot and cold-water system. These were not present on the previous year’s round of sampling, and there was no documented loss of control during the previous 12-month period. A systemic disinfection was completed in response to the site-wide positives for immediate risk mitigation, whilst root cause analysis was undertaken. The trust had a policy of three clear / not detected results as being the required outcome to close the matter, given it was a site-wide problem.

The system was disinfected with 50ppm of Hydrogen Peroxide for a 2-hour contact time due to the size of the system. Following the systemic disinfection, and in line with HSG274 Part 2 paragraph 2.132, sampling was undertaken 2 days post-systemic disinfection to measure the impact of the process. The first set of post-disinfection samples showed no positive results in either the hot or the cold-water system.

The second round of post-disinfection sampling was undertaken the following month. The system returned negative results for all the cold systems. One month after a set of “not detected” post-disinfection results, the hot system had numerous positive results, which indicated that some form of systemic issue remained in the hot water system.

Ongoing root cause investigations revealed that all 3 calorifiers on site were operating at between 38-42°C.

There was no evidence in the site logbooks of monthly monitoring of these assets by the incumbent PPM contractor who was appointed to undertake this task. It was therefore unclear how long these assets had been operating in the peak zone for legionella growth as set out by ISO11731 for legionella culture plates.

With an initial clear cause for Legionella growth identified, a program of daily flushing was instigated with every asset on the hospital site included while the calorifiers were repaired….

However, upon further investigation, it was identified that these calorifiers had temperature restrictions applied by the manufacturer. These were set below the levels required for full pasteurisation. A full investigation into the calorifiers discovered that these particular units could not be pasteurised without bypassing all the temperature and pressure control systems. Furthermore, the model installed was an old and discontinued product that had been specified and installed by the PPM contractor when previous cylinders reached the end of their usable life.

The calorifiers clearly needed to be replaced with units correctly specified for the site, and as a priority. This led to a capital expenditure that had been allocated for other works having to be redirected to replace the current calorifiers with new calorifiers that could deliver thermal control, the primary control measure used by the site.

Sadly, the calorifiers were not initially installed correctly by the specialist contractor. Some dead legs were created when non-flow-through expansion vessels were incorrectly installed. This was highlighted by the temperature monitoring staff as part of the ongoing daily flushing of the site. Once rectified, by the installer, a full pasteurization of both the water storage and distribution system was undertaken. Had this installation been undertaken by an LCA registered company, then one would expect a more competent installation due to having audited management procedures and processes for such installs.

The full system was temperature monitored, via the ongoing daily flushing of the site, for a 6-week period. The ongoing monthly sampling following new cylinder installs showed that the hot water system now had no positive Legionella results across the site, apart from one ward. And this is where the fun really starts….

The ward where legionella didn’t die…

With the systemic issues resolved, focus was now placed on a single ward. This was flagged as an issue as it repeatedly provided positive Legionella results in the hot water monitoring program despite the rest of the site now delivering 4 consecutive “not detected” Legionella results in the hot and cold water systems.

The first approach was to apply an injection disinfection to distribution lines of the ward. This was achieved by applying 100ppm of Hydrogen Peroxide with a 2-hour contact time. The aim was to target potential biofilm that appeared to be present on the wards water system.

The post-disinfection laboratory results showed no real change in Legionella levels. We did, however, start to notice patterns emerging. The first, obvious and interesting fact was that Legionella Species, confirmed by MALDI-Tof at a UKAS-accredited laboratory, was nearly always Legionella anisa (L. anisa). This pattern was compared to records of 13,500 previous laboratory results for Legionella over a 33-month period. The same pattern was observed.

Given that Legionella was still prominent in the system a second disinfection was undertaken a month later. This time all the strainers were removed and disinfected, independently. The system was then disinfected minus the strainers. The Biocide of choice was again Hydrogen Peroxide with the aim of targeting all the remaining biofilm. All strainers were re-installed post disinfection.

Three days passed, and all the system strainers were again removed, cleaned, and disinfected. This was done in case any biofilm had sheared off after the disinfection and may have been trapped in the strainers. Samples were taken again after two days, following the completion of all disinfection works through systems and strainers from the ward distribution system. Positive results kept coming…..

This led to more investigation of the wider systems. It was noted around 15 years ago that the ward had been refurbished, the central distribution remained original Copper. However, all the local drop-downs to this ward were installed with plastic pipework with crimped fittings. Further research identified that these components, at the time of installation, were predominantly used for under-floor heating pipework; the type of piping is now common on cruise ships with WRAS approval since 2016*. To compound matters, there was no insulation of the pipework post the main centralized copper distribution network. This allowed for heat transfer and is clearly a major problem.

A group discussion was held on the best way forward given the unique scenario. This group included water management contractors AE(W), two further AE (W)s (client and sub-tenant representation), the trust responsible for the property, their tenant and associated infection control teams. It was agreed via a TEAMS meeting that a change of chemical should be implemented to see if bacteria in this specific area had built up a tolerance to Hydrogen Peroxide, and the shock of a new chemical might help. Chlorine was to be applied to the system at 100ppm for a 1-hour contact time to see if it would impact the Legionella counts. Sadly, it did not.

Given that the system had undergone disinfections for three consecutive months, it was decided that the system required a month of no treatment to allow it to settle down. At this time, discussions were taking place to see if this would become a live COVID ward. This would have a direct impact on access to the area, root cause analysis and risk mitigation works. It was decided to install a permanent Chlorine Dioxide dosing unit to the Water Storage Tanks providing feeds to the hot and cold-water systems in order to aid risk mitigation; however, these were 25 meters in the air and in a confined space. The decision was made that these should be moved, and this, compounded by the ongoing plumbing challenges, resulted in a decision being made to fully upgrade the associated plant and equipment.

The upgrade consisted of 2 new GRP tanks, 2 brand new booster pump arrangements, a continuous Chlorine Dioxide dosing unit was installed, and the water softener was relocated and upgraded from a Simplex to a Duplex unit.

Throughout this entire period, every asset across the whole hospital was being flushed twice a week, with every asset on the problem ward being flushed for a minimum of 5 minutes every day. Further to this 92-day Laminar Flow tap and Medical Shower Filters were installed to all assets within the problem ward to protect patients from waterborne pathogens. Monthly sampling, both pre- and post-flush on all outlets, was planned and executed over this time in line with the water safety plan. The ongoing positive results (pre-filtration) on the ward with significant bacterial counts left the infection control teams with concerns over staff and patient welfare, in order to provide assurances to infection control teams that immediate risk mitigation was effective in protecting patients, staff and visitors to the ward; when filters were installed (and each time they were replaced) pre-flush sampling was also undertaken through the filter as well as the system. Continued “not detected “results post-filter provided the assurances required while ongoing works were being undertaken on root cause analysis.

When you think it can’t get any worse…

To compound the challenges associated with this ward, it was converted into a COVID-positive ward on New Year’s Day 2021 and remained this way until April 2021. This added to the challenges in managing Legionella control – from simple access issues for flushing or monitoring temperatures, through to being able (or not) to make any physical changes to the plumbing.

When the ward became accessible, despite COVID patients still being treated on the ward, a site visit was undertaken to review the pipework and the potential for pipework re-configuration was discussed. It was noted that this “challenging” ward was the only area in the hospital with plastic pipework and the only area with ongoing bacterial concerns. During this meeting, it was agreed to remove parts of the pipework and undertake swab sampling on the pipework and associated fittings to confirm whether this combination of conditions was just a coincidence.

The swab results identified that the pipework was clear for Legionella. Some of the fittings however were positive for L. anisa.

The swab data and results led to a further meeting with the trust, tenants and Authorising Engineers. The group reviewed some pipework and fittings that had recently been removed from the system. At this point, it was discovered by all that a large amount of jointing compound was on the outside and inside of the plastic pipework. Concerns were also raised regarding the jointing material used. It was agreed by all parties that the plastic pipework and fittings with associated jointing compound would have to be removed to reduce the Legionella risk. Had the ward been piped correctly in the original install, then the scale of the Legionella risk may have been drastically reduced, if not removed entirely.

The re-plumbing of the system was due for completion by the middle of September 2021 and the early results from this suggest that the positivity rate has dropped by over 95%.

There are Lies, Damned Lies and Statistics…

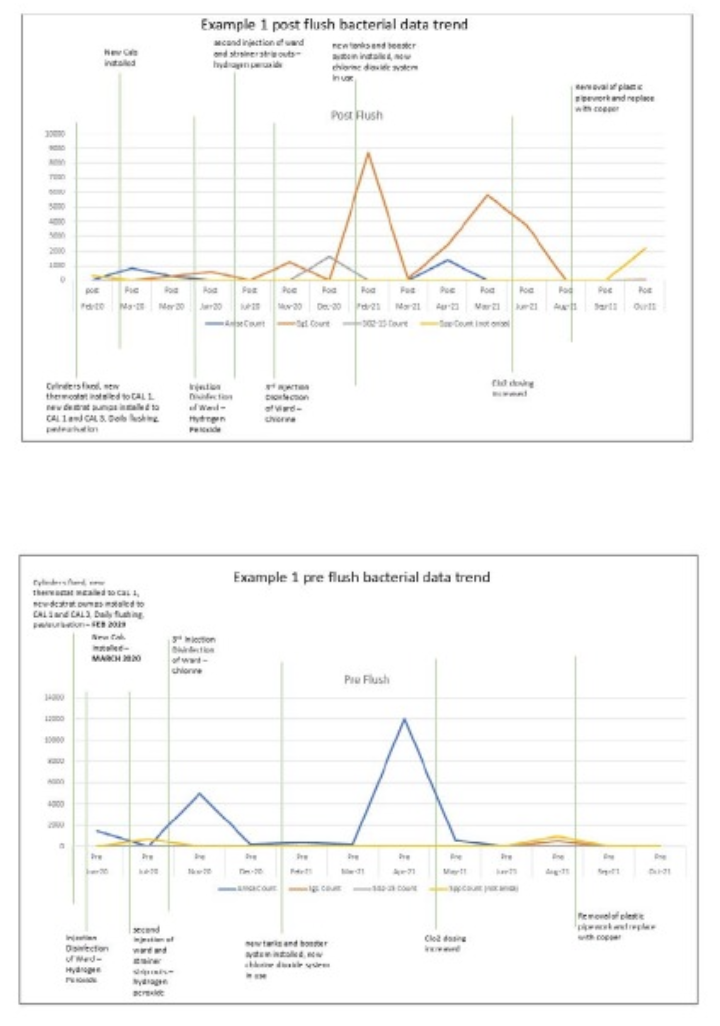

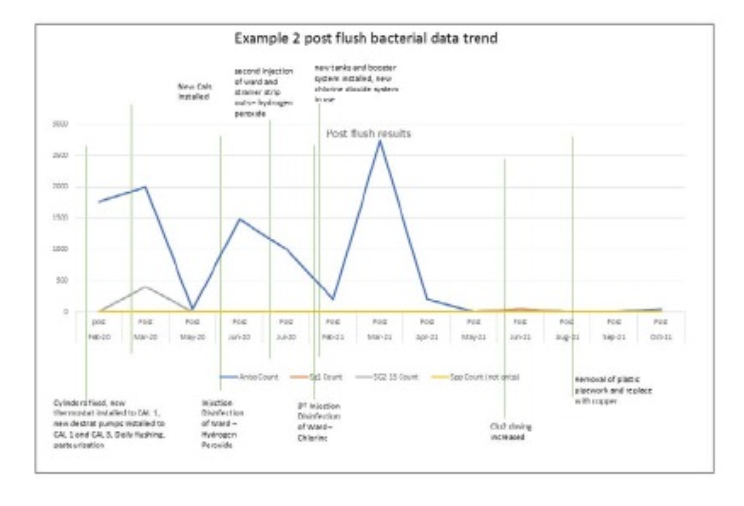

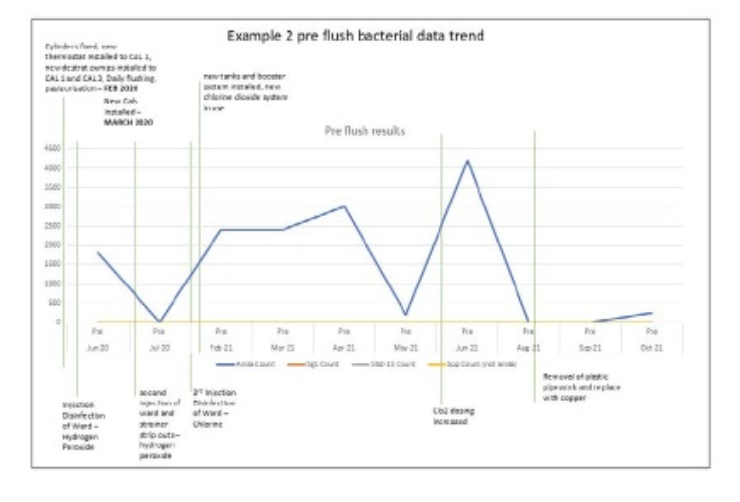

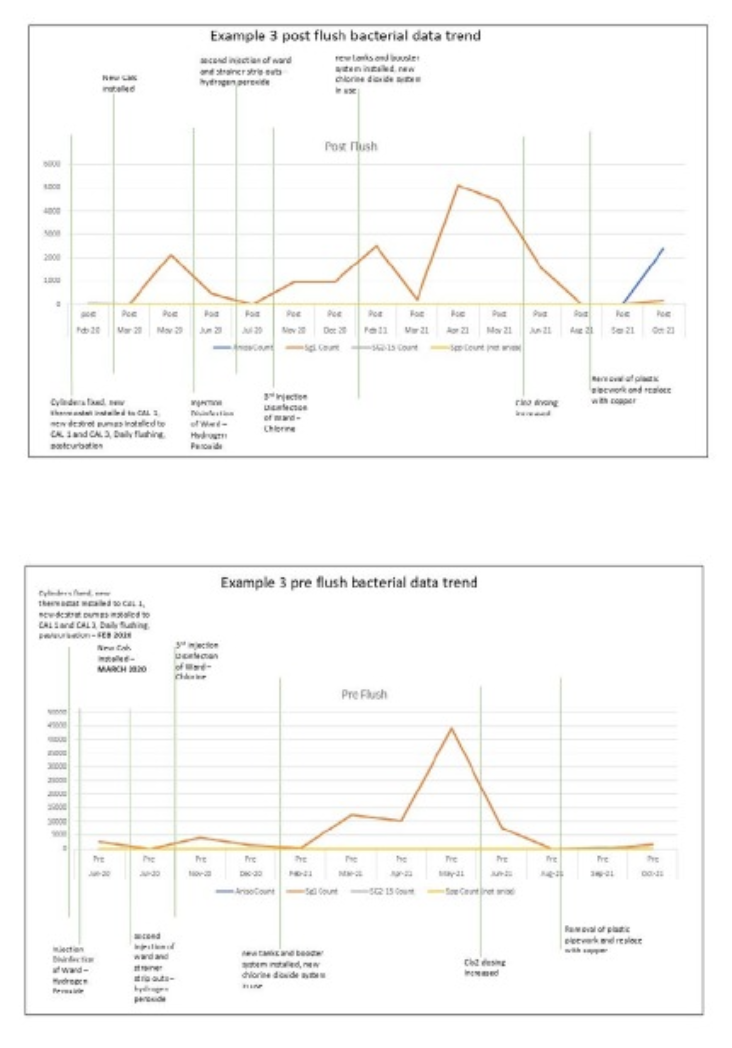

The examples below highlight the interaction of L. anisa, L. pneumophilia SG1 and SG2-15 with the different chemicals that have been applied to the system.

Example one shows how L. anisa appears to outcompete the other legionella bacteria that are present in the system; some of these come to the fore as L. anisa counts reduce, this is most prominent in the pre-flush results.

The second example dataset shows how L. anisa typically behaves on this site in areas where there are less competing legionella bacteria in that part of the system. Note how even post the remedial works the L. anisa infection appears to be coming back in certain areas of the system.

Example three is a prime example of how the L. pneumophilia serogroup 1 responds to the different treatments, both pre- and post-flushing. Notice how in April and May 2021, the increase pre-flush starts to present itself post-flush, with no L. anisa competing with the L. pneumophilia SG1 strains for hold within the system. Interestingly, and curiously, L. anisa seems to have established itself around this asset post the re-plumbing works, as demonstrated by the October 2021 result.

The filters successfully protected patients once the issues were identified and the filters were deployed. Installed for over 12 months the filters offered total retention of system Legionella bacteria throughout their deployment cycles.

One sample provided a positive result of 21CFU/L. This is exceptionally unlikely to have come through the filter due to the nature of their design and function. If a filter was to fail, it fails catastrophically, allowing all pathogens through. The likely cause of this positive result is either retrograde contamination or cross-contamination of the sample, either at the point of sampling, transport or analysis.

The performance of the filter was not impacted by the various treatment processes deployed or the varied Legionella counts, which ranged from not detected up to over 40,000 CFU/L.

What was the cost of this to the Trust?

The title of this paper asks questions about the cost of not doing things right. The “additional” monetary cost to the Trust on this project include:

- Daily flushing works over 21 months cost around £150k

- Monthly sampling of the ward over 21 months, costing around £30k

- Four Systemic disinfections costing around £5k

- TMV servicing and remedial works costing over £5k

- New calorifiers costing around £30k

- New Chlorine dioxide system costing around £30k

- New water tanks and booster systems costing around £40k

- PoU filters for numerous cycles costing £25k

- Re-pipe of the system costing around £50k

These costs amount to around £350,000.

There is also an obvious human cost involved in this, not just from the disruption to the ward and added pressures on ward staff, but also to the patients and families, including decanting the ward to another hospital location, 30 30-mile and 50-minute drive from the current location.

What questions has this experience raised?

There are clearly some root causes to the issues raised in this review. From specification issues around Calorifiers and the use of Plastic Pipework to questions about the impact of sampling 48, 72, 96 or 120 hours post disinfection and the impact on results and the resistance of L. anisa to a range of chemical and thermal treatments.

Other interesting patterns in the dataset raise further questions. The full dataset on this site suggests that L. anisa and L. pneumophilia can co-exist in low numbers; however, when the counts of L. anisa reach around 1,000 CFU/L, the mixed colonies disappear, and L. pneumophilia is the victim. This poses a range of microbiological questions:

- Is annual testing of sites that have no record of a loss of control sufficient given this example?

- Is “plumbers putty” a high nutrient source for bacteria?

- Some samples have only L. anisa positives, does this mean that L. pneumophilia is not present in the pipework? Or is its presence being masked by other species on the culture plate? What is the real microbiological situation in the pipework itself?

- Is the L. pneumophilia a concern if it’s being masked by another species?

- Would L. pneumophilia be found by rapid tests that target specifically L. pneumophilia SG1 where the culture method failed to detect?

- How big a problem is L. anisa in the Water industry?

- How much more does the culture test support the growth of one L. spp over another?

- Does the incubation temperature for the culture test encourage certain species to grow over others?

- Are the counts an error by the laboratory in selecting too few colonies to confirm the type of Legionella present? I.e., would a wider spread of colonies or more colony picks confirmed by MALDI-ToF give a wider spread of species?

- Should we consider testing Legionella at the current temperature (36°C) and also undertake a test at “system” temperature (conditions)? What impact would this make and what would it show?

- Should the AE be involved in the purchasing process to ensure correct specification of equipment?

- Should all major plumbing work undertaken in healthcare settings, that could have an impact on the microbiological load, be completed by LCA registered member companies?

Conclusions

The prominence of L. anisa in the “challenging” ward appears to have been supported by poor system conditions over an elongated period. There were several factors that exacerbated this issue including:

- Incomplete monitoring of the hot water source plant

- Incorrect specification issued to the trust for calorifiers by primary contractors

- Over reliance on contractor specification by estates teams instead of referring uncertain specifications for major plant equipment back to Authorising Engineers for approval and sign off

- No audit/checks on the original PPM tasks being completed

- Calorifiers unable to reach pasteurisation temperatures

- Access & working at height issues for installing the Chlorine Dioxide permanent dosing plant to Storage Tanks

- Impact of the excessive use of “plumbers’ putty” as a food source for bacteria

- Use of incorrect components in plumbing this system

What is unknown is the impact of each individual issue above; only the combined effects and questions should be asked about how much Legionella growth, of any species, would be encouraged by each of these issues on their own.

Further research is required regarding the ability, or not, of L. anisa and L. pneumophilia to be able to co-exist on an ISO11731 culture plate. The preliminary data of 13,500 samples held by HCLp’s AE suggests that co-existence is not possible with counts over 6,000CFU/L of L. anisa, but this could be impacted by a range of factors, including the number of colonies selected for identification via MALD-ToF, among others.

The data suggests that, given the right conditions Legionella can continue to thrive even with a range of treatments in place and the only protection to patients, staff and visitors, in this case, was Point of Use filtration. How many other sites have these continuous issues that are not being protected with the same level of vigor?

Another area that raised industry questions is that the re-pipe of the ward has now been completed and has been undertaken using copper crimped connections (mapress/pressfit type install) – with this pipework using EPDM as a jointing material and EPDM flexible hoses being a none approved item in healthcare facilities since 2010, is this a suitable install type for healthcare properties, what will the long term effects of the use of this install be in a healthcare environment

Ultimately, this site had a plethora of problems that all created a scenario where Legionella could not be removed from the system. The cost to put these issues right was in excess of £300k.

The main question that this paper seeks to ask is whether the challenges highlighted in this document are unique or whether there are similar challenges with Water Systems across the UK.