This special report introduces small area estimation (SAE) as a modern approach for producing reliable, stand-level forest inventory information

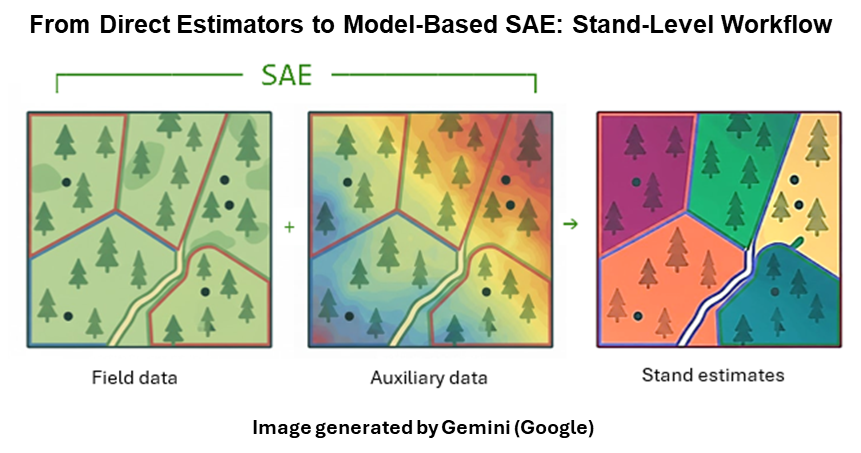

Small area estimation (SAE) is a set of statistical tools that helps estimate what a forest stand looks like, even when there are very few or no ground measurements in that stand. For managers who need to plan harvests, protect wildlife, or track carbon, SAE offers a way to turn scattered plot data and wall‑to‑wall remote sensing into detailed, stand‑level information on forest attributes such as tree sizes and densities (Fig. 1).

Why traditional methods struggle

In practice, most forest stands have only one or two sample plots, and many stands are never measured at all. A few small plots cannot fully capture all the variation within a stand, such as dense patches, gaps, or unusual microsites, and measuring more plots across every stand is simply not feasible. As a result, “direct” estimates based only on field plots are often noisy or unavailable at the stand level, which is problematic when decisions and regulations demand precise numbers.

What small area estimation does

SAE tackles this problem by “borrowing strength” from extra information beyond the field plots. It uses models that connect measured plots to a wide range of supporting data—such as satellite imagery, aerial photos, and maps of climate, soils, and terrain—to predict stand characteristics in areas with little or no ground data. In simple terms, the method asks: “Given what is seen from the air or space, and what is known from similar stands with plots, what is the most reasonable estimate for this particular stand?”

Using remote sensing and maps

Modern forest inventories can tap into several free or low-cost data sources, such as 3D data products generated from stereo imagery (e.g., USDA-NAIP program), satellite data from Sentinal-2, and LiDAR-based elevation canopy products. These sources provide continuous coverage across entire landscapes, capturing features such as canopy height, greenness, and site conditions closely related to tree size and density. By aligning these data sets with plot locations in time and space, SAE models learn how the remote signals relate to on‑the‑ground measurements and then apply that knowledge across all stands.

Focusing on diameter distributions

A key target for these methods is the “diameter distribution” of a stand—the full spread of tree trunk sizes, not just an average. Knowing how many small, medium, and large trees are present supports growth and yield modeling, wildlife habitat assessment, and estimates of wood volume and carbon. SAE models can estimate not only summary measures (like the mean diameter) but also the shape of the entire distribution or the number of stems in different diameter classes, providing a stand‑level “tree size profile.”

Making estimates more robust

Real‑world data are often messy: some plots are measured incorrectly, some stands are very unusual, and some remote‑sensing pixels do not match the ground for various reasons. Classical statistical models can be thrown off by such outliers, leading to biased or unstable estimates, especially when sample sizes are already small. Robust SAE methods are designed to lessen the influence of extreme or suspicious values, so that a few odd stands or plots do not distort the broader picture used for biomass mapping, carbon accounting, or policy reporting.

Adding machine learning

Newer SAE projects are blending traditional statistical ideas with machine learning methods such as tree‑based models and neural networks. These algorithms are good at detecting complex, nonlinear relationships and interactions—for example, how combinations of canopy structure, spectral color, topographic position, and climate together predict tree size and density. Within an SAE framework, machine learning models provide strong predictions, while the SAE framework supplies statistically valid uncertainty estimates, helping keep the models interpretable and consistent with forest survey principles.

How this helps at the stand level

In stands that have several reliable plots, SAE methods give more weight to the direct field information and use the model mainly to refine those estimates. In stands with only one plot—or none—the model relies more on the synthetic prediction from remote sensing and other covariates, effectively filling in the gaps where traditional methods would fail or be too uncertain. This allows managers and organizations to obtain consistent stand‑level tree lists and other metrics across their entire management area, instead of having high‑quality information in a few places and almost nothing elsewhere.

Practical value for forest management

By combining field plots, remote sensing, robust statistics, and machine learning, SAE can deliver more accurate and spatially complete stand‑level estimates at a lower field cost. This supports better decisions about harvest scheduling, habitat conservation, and compliance with carbon and climate reporting standards across diverse forest types. As inventories move toward larger scales and tighter budgets, SAE’s ability to turn sparse measurements into reliable, stand‑level forest metrics makes it a particularly promising tool for the future.