Scientists have developed a genetic risk score that can flag which women with abnormal breast cells could progress to invasive cancer

Researchers at King’s College London have developed a new approach to assessing breast cancer risk that draws on genetic insights. Their study examines how inherited variations may help distinguish which women with early abnormal breast cell changes are more likely to progress to invasive disease, offering potential for more targeted prevention strategies.

The findings are detailed in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

Predicting the risk of breast cancer

In a world first, the researchers have shown a connection between a person’s genetic risk score and their risk of developing invasive breast cancer after irregular cells have been detected. A genetic risk score estimates a person’s inherited likelihood of developing a disease or trait by combining the influence of multiple common genetic variants.

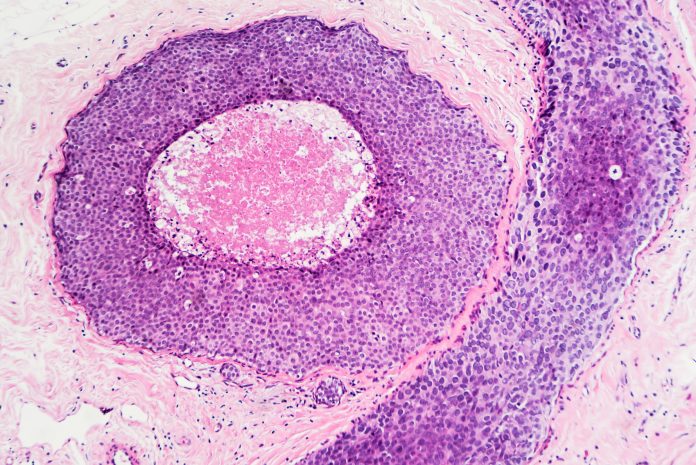

The researchers studied over 2,000 women in the UK who had been tested for 313 genetic changes, known as a genetic risk score. These patients had already been diagnosed with either ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) – the most common types of abnormal cells found in breast tissue.

Screening is offered every three years to women aged 50-71 through the NHS Breast Screening Programme, which uses mammograms to detect early signs of breast cancer. However, this has led to many women being diagnosed with abnormal cells in their breast tissue, which are not invasive cancer but could become cancer in the future. It is not possible to know which women with abnormal cells will go on to develop invasive breast cancer, currently.

Genetic testing breakthrough

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, with around 55,000 women diagnosed each year in the UK. The earlier breast cancer is diagnosed, the better the chance of successful treatment, so being able to predict who might be at risk is crucial.

Jasmine Timbres, first author and Clinical Information Analyst at King’s College London, emphasized the significance of the research, stating, “Our initial results are promising. Predicting who is most likely to develop invasive breast cancer is crucial for offering the best possible treatment options for women, as not all with DCIS or LCIS will progress to invasive cancer.” This research is a significant step forward in the field of breast cancer treatment.

The results of this study indicate that the genetic risk score may be useful in this prediction, suggesting that treatments could be more personalised, rather than applying the same treatment approach to everyone. In some cases, this could avoid unnecessary invasive treatments altogether, which can take a toll on patients both physically and emotionally. Focusing more on individual risk could improve overall wellbeing and help reduce the stress that comes with being overtreated.”

Professor Elinor Sawyer, senior author and a Consultant Clinical Oncologist at King’s College London, said: “In my clinical practice, I see many women diagnosed with DCIS or LCIS. Until now, treatment decisions have been largely based on how the cells appear under a microscope. Our research shows that a genetic risk score can also help predict which women are more likely to develop invasive breast cancer.

“This means we shouldn’t just focus on the cells themselves, but also take into account a woman’s genetic risk and lifestyle factors. By considering the full picture, we can provide women with more accurate information about their personal risk of recurrence. This helps them make more informed choices about their treatment options and what’s right for them.”

Dr Simon Vincent, chief scientific officer at Breast Cancer Now, said: “This study offers evidence that genetic risk scoring could be a useful tool for predicting future breast cancer in women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ or lobular carcinoma in situ, which are the most common pre-invasive abnormal cells found in the breast. Understanding who is most likely to develop invasive disease in the future could help to tailor care for those most at risk, inform treatment decisions and improve individual wellbeing for women.

“While these initial findings show promise for paving the way for more personalised treatment decisions in the future, more research is needed before this test can be used more widely.”