Although its health impacts vary between regions depending on geography, socio- economic status of affected communities, and political policies, climate change is the single greatest threat to human health

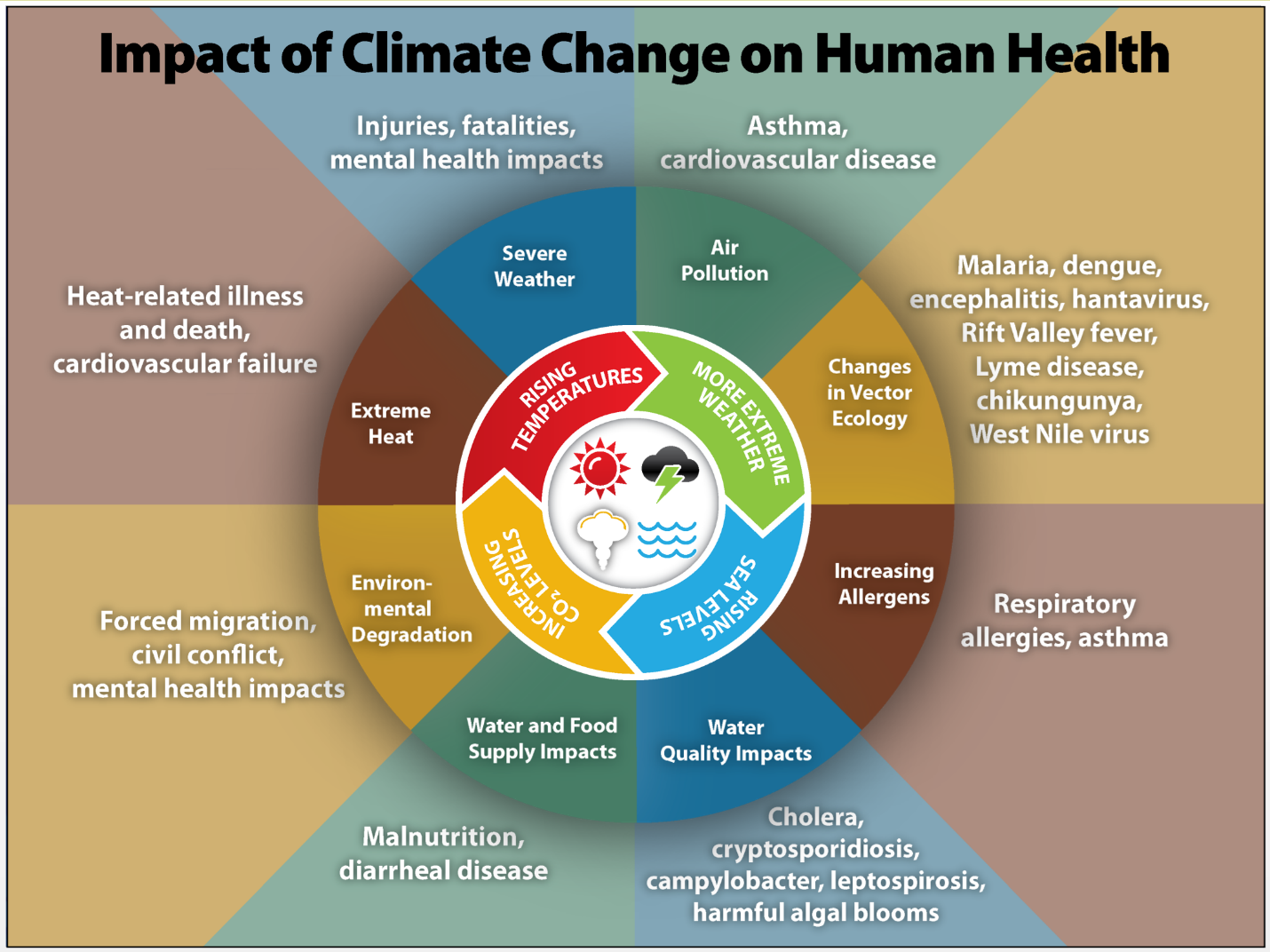

The impact of climate change on human health is further complicated by the fact that it represents the cumulative effect of many interconnected processes (Figure 1). Ironically, those in developing countries and disadvantaged communities who have contributed the least to the global climate change crisis are at the greatest risk for adverse health effects. Those at most risk are least likely to have the resources to protect themselves and are more likely to have risk factors that increase their vulnerability to climate change-related health risks.

It is increasingly appreciated that climate change negatively affects not only physical health, but also mental health. Immediate climate change events like natural disasters can lead to physical injury or death. Long-term climate changes, such as rising global temperatures, can result in food and water insecurity, respiratory disease and allergies, and heat-related illnesses. Similarly, the mental health effects of climate change may be immediate or develop over time and may result from direct or indirect effects of climate change. Immediate and direct mental health effects are most obvious in the aftermath of an extreme weather event or natural disaster like flooding, hurricane, or wildfire.

Trauma and shock are among the most common psychological responses observed following an acute climate change-related disaster, and these effects often subside with the restoration of safety and security. However, survivors of acute climate change-related disasters may experience chronic or severe mental health disorders related to stress, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, and substance abuse.

Prolonged climate events like extreme heat and drought also affect mental health. Extreme heat can affect mood and behavior, and individuals with pre-existing mental health problems or substance abuse disorders, as well as those on psychiatric medication, tend to have more difficulty with maintaining thermal homeostasis and are therefore at a greater risk of experiencing heat-related health issues. Extreme heat events are associated with spikes in hospital admissions for mood and behavioral disorders, like schizophrenia.

Heatwaves can also exacerbate substance abuse because individuals with substance abuse disorders often turn to alcohol or other substances of abuse to cope with the discomfort caused by exposure to extreme heat.

Research on the toll climate change is exacting on human mental health is rapidly expanding as extreme weather events are becoming more frequent, intense, and complex. Here, we discuss the emerging scientific literature on this topic, and discuss new terms that are used both in scientific publications and on social media platforms to describe the emotional responses triggered by climate change and the impacts of the climate crisis on mental well-being.

The impacts of the climate crisis on mental well-being: What is eco-emotion?

Climate change-related events are happening worldwide, and the globalization of climate- related news regarding geographically distant climate events allows this information to reach a global population. The framing of climate change coverage on social media and news platforms affects our perception and understanding of the climate crisis, which can in turn trigger negative emotions like grief, depression, anxiety, distress, or anger. Additionally, individual experience with the direct and indirect impacts of climate change combined with increasing awareness of the overarching problem facing humanity worldwide due to the growing climate crisis can trigger these eco-emotions.

• Eco-grief

Eco-grief is a type of emotional response to ecological change associated with the physical loss of a personally significant place, such as a home, natural place, ecosystem, or community. Eco-grief stems from the concept of biophilia, which refers to an innate connection with nature and other living beings that provides psychological and emotional benefits. Climate-related changes that trigger eco-grief may have already happened or be anticipated to happen, for example, the loss of land due to rising sea levels or the extinction of a species due to habitat loss.

A climate-related loss of personal significance can contribute to the loss of personal identity or disconnection from an individual’s community. This has happened repeatedly to indigenous people all over the world with both physical and mental repercussions spanning generations. Now we are all experiencing eco-grief to some degree as we see changes in normal weather patterns exerting changes on ecosystems.

• Eco-depression

Eco-depression refers to feelings of depression triggered by predicted future effects of climate change. Individuals experiencing eco-depression often feel helpless or powerless to change the course of the climate crisis. Individuals who identify as being eco-depressed are more likely to experience other mental health issues, such as depression, anxiety, and stress. Eco-depression is often fueled by news reports, as well as information posted on social media platforms. Reported cases of depression increased sharply in the aftermath of the 2019 Australian bush fire that burned up to 19 million hectares of land (Figure 2) and the extreme flooding in South Korea during the summer of 2022. International media attention on such events are forcing people to realize that the climate crisis is not an isolated event and that it is disrupting the lives of ordinary people.

• Eco-anxiety

Climate anxiety and eco-anxiety are other eco-emotions caused by stress, fear, or worry about future global threats associated with climate change. Anxiety is an emotional flight response to avoid real or perceived danger.

Mechanisms for coping with eco-anxiety include becoming informed about and finding potential solutions for stressful or dangerous climate-related situations. However, because climate change is such a complex problem with no clear solution, anxiety about the changing climate can become intense and overwhelming. While some people cope with eco-anxiety by protesting to raise climate awareness (Figure 3), others are almost paralyzed by eco-anxiety and unable to act. They may feel shame and guilt, further intensifying their climate anxiety.

Increasingly experienced by the general population globally, eco-emotions, such as fear, worry, anger, grief, despair, guilt, and shame connected to climate anxiety, are considered a normal response as individuals globally become more aware of the situation, accept it, and develop mechanisms for coping with the climate crisis.

The rise of climate anxiety and depression in children, young adults and survivors

Climate-related distress is especially prevalent among children and young adults as they consider their future, including whether to have children of their own. In 2018, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change announced that policy makers have 12 years to enact policies to prevent the potentially irreversible consequences of climate change.

Children and young adults today are realizing that they may be experiencing a “point of no return” for the planet and as a result are likely to experience the worst realities of climate change in their lifetime, even if the worst disasters may occur 70 to 90 years from now.

In a survey conducted by The Lancet involving 10,000 young adults aged 16 to 25 from ten different countries, 60% of the respondents indicated that they felt very or extremely worried about climate change and nearly half of the participants felt that their feelings toward climate change was impacting their daily lives.

A large proportion of respondents who identified as being extremely worried about climate change lived in India, Brazil, and the Philippines, countries already heavily affected by climate change. When asked about their perception of their government’s response to climate change, over 60% of respondents felt that their government was failing them and believed that their government was either lying to them about the impact of the climate actions taken by the government and/or was dismissing their concerns. The growing psychological impact of climate change on children and young adults is partially rooted in relational factors with the adults in their lives. The former can feel confused, angered, betrayed, or abandoned when adults fail to acknowledge or mitigate climate change caused by the actions of older generations who may not care because they will not live to see the worst of climate change.

Emerging research on people who have experienced climate change-related disasters indicates that eco-anxiety lingers in survivors. A survey of 2005 Hurricane Katrina survivors found that while 5 to 8 months after the hurricane 14.9% of survivors experienced PTSD, the rate increased to 20.9% one year later. In another survey conducted between 2002 and 2003, residents from 30 locations in Wales and England who experienced flooding or lived in at-risk flooding areas since 1998 self-reported having anxiety associated with rain 2.5 to 5 years after the flooding event. Heat-related climate change events like wildfires have similar mental health effects. In a survey of victims who experienced major losses in the Ash Wednesday Australian brush fire of 1983, 42% of the respondents were identified as a “potential psychiatric case” a year after the event. Thus, researchers are finding that the psychological impact of experiencing a climate change-related disaster can persist for years and be exacerbated by subsequent occurrences of the triggering event (e.g., rain, fire, heat).

Why our mental well-being is vulnerable to climate change

The mental health outcomes associated with climate change-related disasters, such as anxiety, depression, PTSD, fatigue, substance abuse, and other psychological disorders, are associated with not only experiencing the event, but also the stress and trauma caused by loss. Some individuals, and in particular children, seniors, people with pre-existing physical and mental health conditions, people with lower socio-economic status, immigrants, and homeless individuals, are especially vulnerable to the potential negative psychological impacts of climate disasters. An inability to access support can further contribute to adverse mental health impacts. Resources to treat anxiety and depression, such as counselling, may often become overwhelmed due to high demand or be inaccessible due to infrastructure damage after a climate-related disaster.

Prolonged climate events like extreme heat and drought can also directly affect mental health, particularly when there is no “end” in sight. Long-term effects of climate change can force change, such as loss of personal or social infrastructure, disruption of food and water supplies, worsening of health conditions, conflict within or between families and/or communities, or displacement. Climate- sensitive industries, like agriculture, are vulnerable to climate-related loss of income, employment, or assets. For example, air pollution resulting from prolonged periods of high temperature can lead to increased respiratory illness or allergies, resulting in increased demand for health care services and reduced capacity to work amongst agricultural workers. These losses are tied to decreased mental well-being.

Disruption of the supply chain as a secondary effect of climate change threatens the economic stability of communities, countries, and regions, which also worsens the mental well-being of the affected individuals. Climate change-induced displacement and eco- migration are predicted to become major socioeconomic issues in the 21st century, especially for low-income individuals as they seek to mitigate the physical and mental strain associated with climate change. Children are especially vulnerable to the mental health effects associated with displacement. Disruption of routine and separation from family or friends along with parental stress contribute to children’s mental vulnerability after climate-related disasters. Adverse childhood experiences, such as living through a climate-related event and the aftermath, have been associated with an increased risk of serious mental and physical health issues throughout life.

The growing stressors caused by climate change-related weather events can be difficult for people already dealing with mental health disorders or those susceptible to anxiety, depression, or suicidal thoughts and ideations. This includes not only experiencing a climate change-related event but also learning about others’ negative experiences with climate change. The latter can exacerbate poor mental well-being because the affected individual identifies new stressors in their life and/or recognizes their own potential vulnerability.

How can we protect and maintain mental health during this climate crisis?

Access to adequate mental health care is the first line of defense against the psychological impacts of climate change. This is a challenge for both developing and developed nations. In many countries, particularly developing nations already disproportionally impacted by climate change, there is a significant gap in resources and social services for mental health. Even in developed countries, gaps in funding and insufficient numbers of trained personal limit the availability of mental health resources, particularly in disadvantaged communities. Mental health problems like anxiety and depression cost the global economy about $1 trillion U.S. dollars annually due to loss of productivity, but governments on average spend just 2% of their health budget on mental health.

There is also an urgent need to educate the general population about the potential mental health implications of climate change. With adequate training, health care professionals, educators, and other community and religious leaders can help individuals and groups recognize and identify climate change-related stressors in their lives. There are effective approaches for teaching resiliency and methods for reducing distress and reinforcing feelings of self-efficiency. Chronic stress during childhood can have long-term health impacts and increase the risk of developing mental health problems in adulthood, so it is especially important that children become familiar with the concept of climate change and all the different ways it can affect them. Educating people about climate change and eco-related mental health provides them with the vocabulary to talk about their feelings and formulate approaches for responding to the climate crisis.

Some countries have acknowledged the importance of considering mental health and psychological support for both individuals and communities in their preparedness and response plans for climate-related emergencies. After Typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippines in 2013, the Department of Health strengthened its mental health support system by creating a training program for health professionals and community health workers to provide mental health care and psychosocial support. In the Caribbean islands, which have been affected by increasingly strong hurricanes due to climate change, the Caribbean Development Bank worked with the Pan American Health Organization to develop a mental health awareness campaign to reduce the stigma of seeking help for mental health. The campaign leveraged the Caribbean cultural principle of “one love, one family” and equipped individuals’ with tools for identifying symptoms of psychological distress and providing support for others in their community experiencing a mental health crisis. The program’s overall goal was to teach caretakers, first responders and volunteers how to provide psychological first aid and how to safely respond and provide initial support for individuals in psychological distress during a disaster. Mental health professionals were heavily involved in planning these health programs, which strengthened the greater mental health community health while reinforcing community connections and social collectiveness following a disaster.

Taking personal action to protect the climate

Taking personal action to mitigate the impacts of climate change, whether small or large, can help individuals confront their climate fears and feel empowered. Small steps include recycling, reducing personal use of plastic, or taking public transportation to reduce consumption of fossil fuels can reinforce feelings of hope and mitigate stress. This is especially true when people see others engaging in the same behavior, reinforcing the concept that the collective effect of individual small steps can make a significant difference. There are also increasing examples of individual actions that have a large impact. For example, in early 2022, the United Nations News covered the story of Nzambi Matee, an engineer from Kenya who started a company to convert plastic waste into building materials. Matee revealed that she was motivated to start her company because she was tired of watching her community in Nairobi, Kenya struggling to manage their plastic waste.

The importance of implementing effective and scientifically robust climate change policies in local and national governments cannot be ignored. This collective concern about climate change is also important to help individuals feel that their voices are being heard and their concerns are being met. Leaders need to enact policies that will mitigate climate change and provide support for climate-positive efforts.

Positive examples include the 26th United Nations Climate Conference (COP26), during which many government parties formed new policies and agreements to reduce forest loss and to decrease greenhouse emissions. In COP26, 100 nations signed a plan to cut methane emissions by 30% by reducing fossil fuel production. In addition, the U.S. along with the United Kingdom, Germany, and Norway pledged $1.7 billion U.S. dollars to indigenous groups to support their work in forest and land conservation. By addressing both the gap in resources for climate change mitigation and mental health, governments can help their citizens adapt and prepare for the evolving climate crisis.

News media also have a significant role to play in mitigating the negative impacts of climate change on mental health. The framing of climate change media coverage strongly influences individual perception and understanding of current climate events. The tendency for media outlets to highlight the doom and gloom of the planet, while effective in gaining the reader’s attention, may exacerbate eco-emotions if not balanced by information regarding mitigation efforts being developed. There is reason for hope as illustrated by a recent report published in Science News, in which researchers from the University of Oxford described an inexpensive way of using planes to capture atmospheric CO2 for direct conversion into fuel. This news highlighting an innovative solution for reducing the carbon footprint of flying, which accounts for 12% of the global transportation carbon emissions, is inspiring and can have a significant positive effect on mental well-being.

In summary, the climate crisis is real, and it is having documented adverse effects on human mental health. It is incumbent on individuals, communities, news media and governments to consider not only how we educate each other on climate change, but also how we protect against the potentially devastating impacts of climate change on mental well-being. After all, good mental health is critical to the development of creative and effective solutions to the climate crisis.

To download this piece from UC Davis, click the eBook available here.