Pioneering sustainable technology centred on humans must be key to the EU’s energy strategy, argues Robert Ackrill, Professor at Nottingham Business School

Staying on the path to net-zero emissions by 2050 means the European Union (EU) must continue investing in renewables as a key priority of its energy strategy. A successful strategy, however, must also ensure the transition is inclusive, with roughly one-in-ten people in the EU currently unable to keep their homes adequately warm.

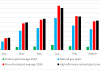

A significant milestone for the 2050 commitment involves the EU cutting its emissions by 55% relative to 1990 levels by 2030. Having reached a 37% reduction by 2023 means this will be achievable if the downward trend remains steady at an average rate of 2.8 percentage points every year for those seven years. This equates to around 134 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent.

To compare, that is over a third of the UK’s net carbon account in 2023, reported at 385 million tonnes of CO2equivalent by the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero.

On its own, cutting this volume of emissions every year would require significant investment in the development and deployment of new technologies. But policymakers are simultaneously faced with the challenge of balancing sustainability targets with other priorities, chief among which are energy affordability, security, and innovation for growth.

Creating a cohesive policy approach

These varied challenges are recognised in the five dimensions of the EU’s Energy Union policy: ensuring security, solidarity, and trust in energy supply; creating a fully integrated internal energy market; achieving energy efficiency; decarbonisation; and research, innovation, and competitiveness.

These aims reflect policymakers’ understanding that green energy must also be affordable and reliable for EU citizens. Indeed, the Energy Union Task Force originated from the development of the Action Plan for Affordable Energy, laying the groundwork for an energy strategy that examines both the costs of renewable energy sources and consumer demand.

Policies must integrate steps to upgrade infrastructure beyond the necessities for green energy generation by making buildings, from business-owned properties to residential housing, more energy-efficient.

Positive energy districts (PEDs) exemplify this approach in practice. The term describes urban areas that generate and produce an annual surplus of renewable energy, while also achieving carbon neutrality through other means, such as green transportation.

However, affordability still presents a significant challenge. Whether building these districts from scratch or retrofitting existing developments, it takes time for the cost of new technologies to lower to such an extent that scalability is possible. It is, therefore, essential to ensure that tackling energy poverty is built into PED design. This requires stakeholders to move away from ‘silo thinking’ and embed systems thinking into design.

With the cost of some renewable sources, such as wind and solar, having already fallen significantly, a pathway is open for PEDs and other forms of development, in social housing, for instance, to combine EU objectives around making energy greener and also more accessible for the public.

Global competition and innovation

Greater affordability is essential to ensure accessibility to new technologies, but the path to delivering it is to boost energy security while also strengthening EU competitiveness, especially vis-à-vis the United States (U.S.) and China.

According to the September 2024 Draghi Report on the Future of European Competitiveness, EU companies face electricity prices two to three times those in the U.S., despite energy prices having fallen considerably in recent years. This limits the funding available for projects that could lead to innovation across sectors, from traditional industries to the digital space and artificial intelligence (AI) development.

Accelerating its transition toward renewable energy sources could help the EU boost its competitiveness. As the cost of implementing this technology decreases, it could help to stabilise prices in the European energy market, in addition to positioning the EU as a pioneer in green technology.

This will be enhanced by integrating the EU’s still fragmented energy markets, allowing for easier trade in energy across national borders as demand and supply shifts permit. Underpinning this will be efforts to boost energy security. The need to move away from fossil fuels is not just about decarbonising energy systems; Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine has shown the vulnerability of being dependent on energy imports from a small number of countries who, as I was once told when interviewing experts, “do not like us very much”.

Decarbonisation, therefore, needs to accompany the diversification of the types of renewable energy consumed and the countries from which energy is imported. Geography and geology have left the EU with a considerable energy import dependency – roughly 60% of energy needs are met through imports.

Furthermore, the transition to renewables raises the issue of supply fluctuations, even daily, not just seasonally. As a result, Europe will need to develop infrastructure to store surplus energy, which can help smooth out supply fluctuations. This will still require imports of vital raw materials, including rare earth minerals such as lithium, which are essential for batteries.

China has proven highly effective in controlling the trade of these types of minerals, both from its own domestic supply and from other parts of the world, such as Latin America. This means the EU must carefully consider its economic relationship with China as it seeks to implement its energy strategy.

An evolving strategy

For the remainder of the 2020s, (imported) fossil fuels are likely to continue playing a central role in Europe’s energy infrastructure. But the Energy Union demonstrates that the EU has already made significant progress towards implementing a framework that will drive forward a multi-dimensional strategy to improve energy sustainability, security, and affordability.

The green transition is positioned as the linchpin which will feed into other objectives. Becoming a leader in this space has significant implications for the continent’s global competitiveness and its reliance on imports, although full strategic autonomy for Europe’s energy sector appears unlikely in the current geopolitical environment.