Natalie Mackenzie discusses the importance of proactive measures for brain health, emphasising the critical foundations of cognitive health and the changes leading to dementia, which can begin up to two decades before symptoms appear, making early dementia prevention crucial

Dementia is a collective term for a group of diseases that affect memory, thinking, and the ability to perform daily activities. According to the latest estimates from 2021, approximately 57 million people worldwide are living with dementia, with over 60% residing in low- and middle-income countries. (1) Each year, nearly ten million new cases are diagnosed. (1) Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type, accounting for 60-70% of all cases. Other forms of dementia include vascular dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, and various conditions that lead to frontotemporal dementia, which involves degeneration of the frontal lobe of the brain. (1)

Many people often think about their brain health later in life, often when it might be too late to make changes. Such thoughts only become a concern during life changes like perimenopause or menopause, when ‘brain fog’ sets in, during an illness, or when a family member is sadly diagnosed with dementia. We often see cognitive decline as a distant problem, something to worry about in our later years. However, a growing body of evidence tells a different story in that the foundations for brain health in our 70s are laid in our 30s and 40s.

Although dementia is most common in older adults, the changes in the brain that can lead to dementia do not happen overnight. In fact, they can begin developing up to two decades before the first noticeable symptoms appear. This long lead-up time is both a warning to be aware of and an opportunity for dementia prevention. It tells us that waiting for symptoms to appear is waiting too long, but it also gives us advance notice to take proactive steps to protect our cognitive and brain health for the future.

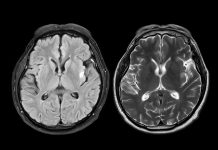

What is happening inside the brain?

At a microscopic level, two processes are thought to play a key role in age-related cognitive decline: oxidative stress and chronic inflammation. You can think of oxidative stress as a kind of biological ‘rust’ that damages our cells, including brain cells (neurons).

Inflammation, while a normal part of the body’s defence system, can become chronic and damaging if it is constantly active. Chronic stress triggers the prolonged release of cortisol, a stress hormone that, in excess, can damage the hippocampus (a critical brain region for memory and learning), which, over time, can impair cognitive function and increase the risk of dementia. We need some stress in our lives to motivate and perform, but there is a fine balance before we move into higher levels of stress that have a negative impact on our brain health.

Our modern lifestyles can often fuel these processes; after all, we were not designed to live in such a busy, fast-paced world, which can add to long-term stress. A diet high in processed foods, a lack of regular physical activity, poor or little sleep, and chronic stress all contribute to a state of low-grade inflammation that can silently impact brain function over many years.

Researchers are making significant strides in identifying early markers of dementia risk. While there is no single test that can predict the future with certainty, science is providing new tools to assess brain health. These include advanced brain imaging techniques that can spot structural changes and blood tests that measure specific proteins associated with cognitive decline. In some clinics, memory and cognition assessments are also used as a baseline, tracking subtle changes over time. These technologies are becoming increasingly accessible, allowing people to monitor their cognitive health as they do with cholesterol or blood pressure. Early detection gives individuals time to seek advice, make changes, and track progress, which can be empowering rather than alarming. Biomarker research is promising, and more early screening is promoted to catch any changes early so that treatment can be provided.

This kind of monitoring is not about causing anxiety or over worry, but knowing your potential risk factors allows you to make targeted lifestyle changes.

Lifestyle changes

The good news is that a significant number of dementia cases are linked to lifestyle factors, meaning they are potentially preventable. The evidence strongly suggests that what is good for your heart is also good for your brain. The key is consistency.

Here are some of the most impactful changes you can make:

Adopt a brain-healthy diet: A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, oily fish, and whole grains, such as the Mediterranean diet, has been shown to support long-term cognitive function. Reach for leafy greens like spinach and kale, berries, walnuts, flaxseeds, and oily fish such as salmon, mackerel, or sardines. These foods are packed with antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds that help combat oxidative stress.

Move more: Regular physical activity increases blood flow to the brain, delivering essential oxygen and nutrients. It also stimulates the growth of new neurons. You don’t need to run a marathon; brisk walking, cycling in the park, swimming, yoga, or even dancing in your living room are all excellent choices. Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise each week.

Sleep must be a priority: Sleep is not a luxury; it is your brain’s essential maintenance period. During deep sleep, the brain clears away metabolic waste products that can build up during the day, which is not only critical for brain health but also for general cognitive performance. Create a restful environment by limiting screens before bedtime, keeping your room cool and dark, and maintaining a consistent sleep schedule. Aim for seven to nine hours of quality sleep per night.

Learn & connect: Learning new skills, engaging in hobbies, and maintaining strong social connections help build what is known as ‘cognitive reserve’, which is the brain’s ability to be resilient and adapt to damage. Try a new puzzle or game, learn a new language, play a musical instrument, or join local clubs to stay active in your community. Loneliness and isolation play a large role in cognitive decline.

References

1. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (Accessed November 2025)