Researchers from MPI-IS and NUS have developed a light-driven 3D printing technique that moves beyond polymers. This breakthrough enables nanofabrication using metals and semiconductors, paving the way for advanced, multi-material robots and medical devices

Scientists have reached a significant milestone in micro- and nanotechnology. For years, the ability to “print” complex 3D structures at a microscopic scale was largely confined to polymers. While researchers could create intricate models like miniature Eiffel Towers, they were stuck using only one type of “ink.”

A new study published in the journal Nature on January 28, 2026, changes that. A collaborative team from the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems (MPI-IS) and the National University of Singapore (NUS) has developed a technique that allows for the 3D fabrication of objects using metals, semiconductors, and carbon materials.

The power of optofluidic assembly: Nanofabrication

The traditional gold standard for tiny 3D structures is two-photon polymerisation (2PP). While precise, 2PP relies on chemical reactions within specific plastics. The new method, known as optofluidic assembly, takes a different approach by using light to move physical matter.

Researchers use a femtosecond laser to create a tiny hot spot within a liquid filled with loose particles. This heat generates a localised fluid flow. By precisely controlling this flow, the team can “push” particles into a pre-designed mold.

“The laser induces a thermal gradient which generates a strong flow,” explains Xianglong Lyu, the study’s first author. “This propels particles into the template exactly where we want them to be.”

Nanofabrication and advanced robotics

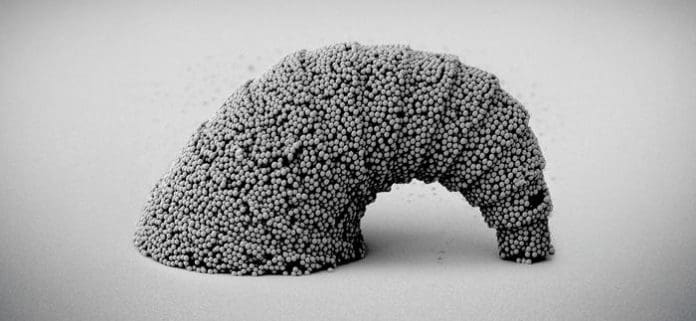

The versatility of this method is immense. Because the process is physical rather than chemical, almost any material can be used as a building block. Once the particles are packed into the desired shape inside a polymer “cake pan,” the mold is removed. The resulting structure remains intact due to van der Waals forces, which are strong molecular attractions that keep the particles together without the need for glue.

The team demonstrated this by creating complex shapes, including a dangling croissant-shaped microstructure made of silica (SiO2).

Beyond artistic shapes, the researchers built functional devices:

- Microvalves: Small enough to fit inside hair-thin channels to sort particles by size.

- Multimaterial robots: Tiny machines that react to both light and magnetic fields because they are built from a mix of specialised materials.

A new era for microsystems

This advancement effectively provides scientists with a full toolbox of materials instead of just one. By moving beyond polymers, engineers can now create tiny components with specific electrical, magnetic, or thermal properties.

Metin Sitti, who oversaw the research at MPI-IS, notes that this technology opens up new frontiers for micro-scale technology and multifunctional robotics. As these techniques continue to mature, the ability to manufacture complex, multi-material machines at the nanoscale may soon move from the laboratory into practical medical and industrial applications.