Sigurður Trausti Karvelsson, the Terraforming Life Project Coordinator and R&D Project Manager at First Water along with project partners; The Icelandic Farmers Association, Orkídea, SMJ Consulting Engineers, and Ölfus Cluster, present an initiative that transforms waste into resources within Iceland’s circular economy

Building the future from waste

In Iceland, a quiet transformation is underway – one that could redefine the relationship between land-based salmon farming, agriculture, and the environment. The Terraforming LIFE project, an ambitious European Union (EU)-funded initiative running from 2023 to 2028, is pioneering circular-economy solutions to one of the nation’s most pressing environmental challenges: organic waste. With five partners and a total budget of €10 million, the project seeks to convert fish sludge, manure, and other organic residues into clean energy and valuable fertilisers.

Its ultimate goal is to lay the groundwork for a waste-to-value infrastructure capable of handling 100,000 tonnes of organic waste annually – an essential step toward a greener and more resource-efficient Iceland.

The growth and problem of land-based salmon farming

Few sectors in Iceland have grown as rapidly as the land-based aquaculture industry. In 2025, production reached 3,000 tonnes of salmon, but forecasts for 2031 predict a fifty-fold surge to 150,000 tonnes. While this growth represents a triumph for sustainable protein production, it also brings an inconvenient by-product: fish sludge.

Every land-based farm is required to filter this sludge, which consists of fish faeces and uneaten feed. Currently, much of it is used for land reclamation; however, the sheer volume expected in the coming years will soon overwhelm this option. Without an alternative pathway, fish sludge risks becoming a costly environmental burden rather than a resource.

Agriculture’s untapped potential

At the same time, Iceland’s agricultural sector faces its own inefficiencies. In 2024 alone, the country imported 55,000 tonnes of chemical fertiliser – an expensive dependence that strains farmers and contradicts sustainability goals. Domestic organic materials, from pig manure to bone meal, remain underused.

A 2022 report by Matís revealed that pig manure, despite being nutrient-rich, is under-applied as a fertiliser. Meanwhile, over 3,000 tonnes of bone meal are produced annually, but seldom reach crop fields. The synergy between these two waste streams – fish farming by-products and agricultural residues – was evident. Terraforming LIFE emerged as the framework to link them.

A vision for the circular industry

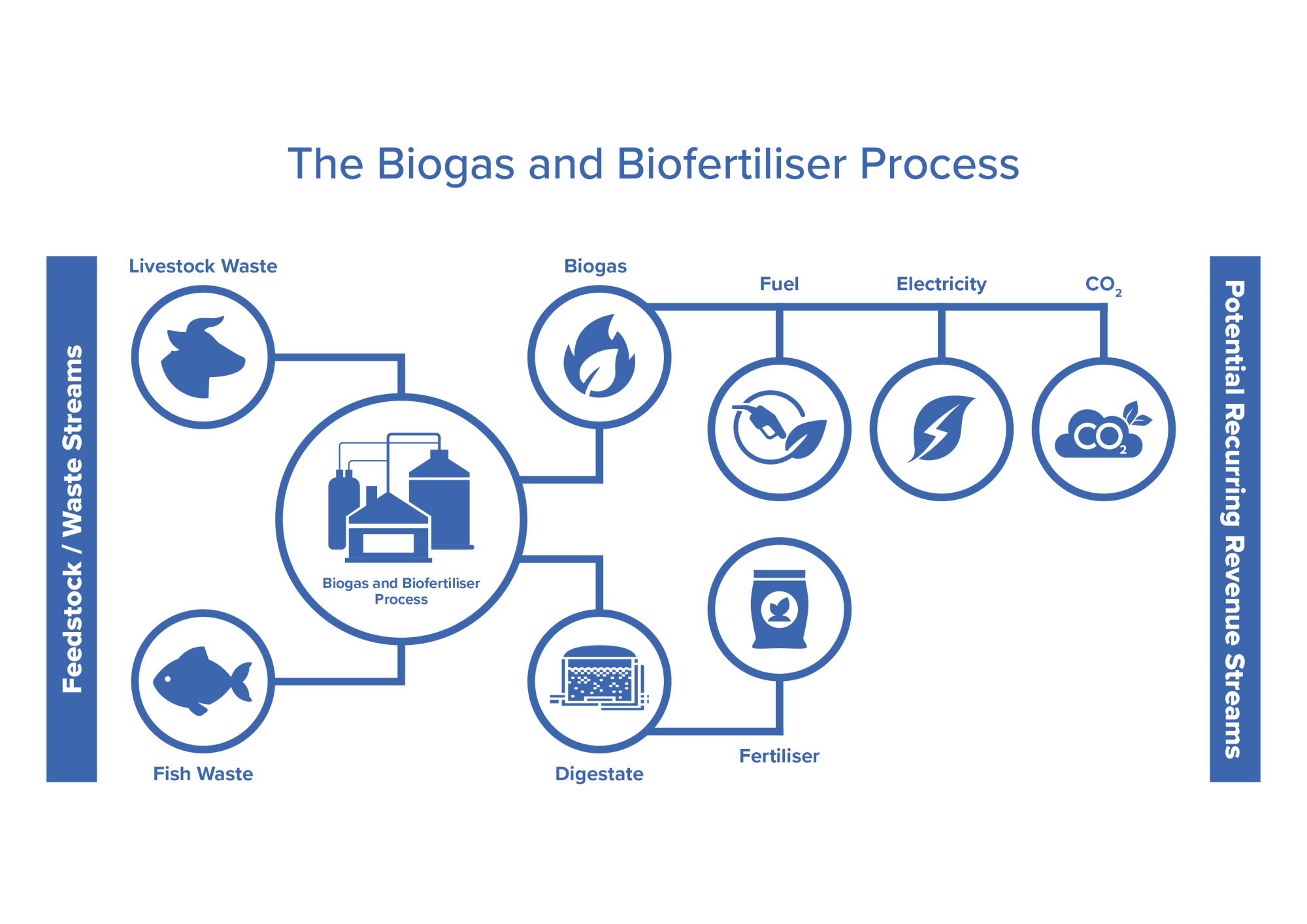

The project’s concept is simple: combine organic waste from fish farms and agriculture, process it through anaerobic digestion, and produce two valuable outputs –biogas and organic fertiliser. The biogas can replace fossil fuels, while the digestate becomes a nutrient-balanced organic fertiliser suitable for Iceland’s demanding soils.

Terraforming LIFE functions as both a pilot and a blueprint. Its pilot facility will handle approximately 30,000 tonnes of organic material each year. The full-scale vision, however, extends beyond capacity – it aims to establish the infrastructure and technical know-how required for Iceland to close its organic-waste loop.

First Water: From salmon pioneer to waste innovator

One of the key contributors, First Water, exemplifies how industry innovation drives environmental progress. The company currently produces 1,500 tonnes of salmon annually, with an ambitious target of 50,000 tonnes per year. Its unique system uses lava-filtered seawater, enabling efficient recirculation and a reduced ecological footprint.

Within Terraforming LIFE, First Water leads the optimisation of sludge- recovery technology. Its engineers have refined tank hydraulics to improve both fish welfare and sediment capture, while designing effluent canals that prevent sludge breakage. A 900 m² drum filter station is now operational, and advanced dewatering units are being installed to reduce transportation and treatment costs.

These technical milestones are not isolated achievements – they form the operational backbone for Iceland’s future biogas plants.

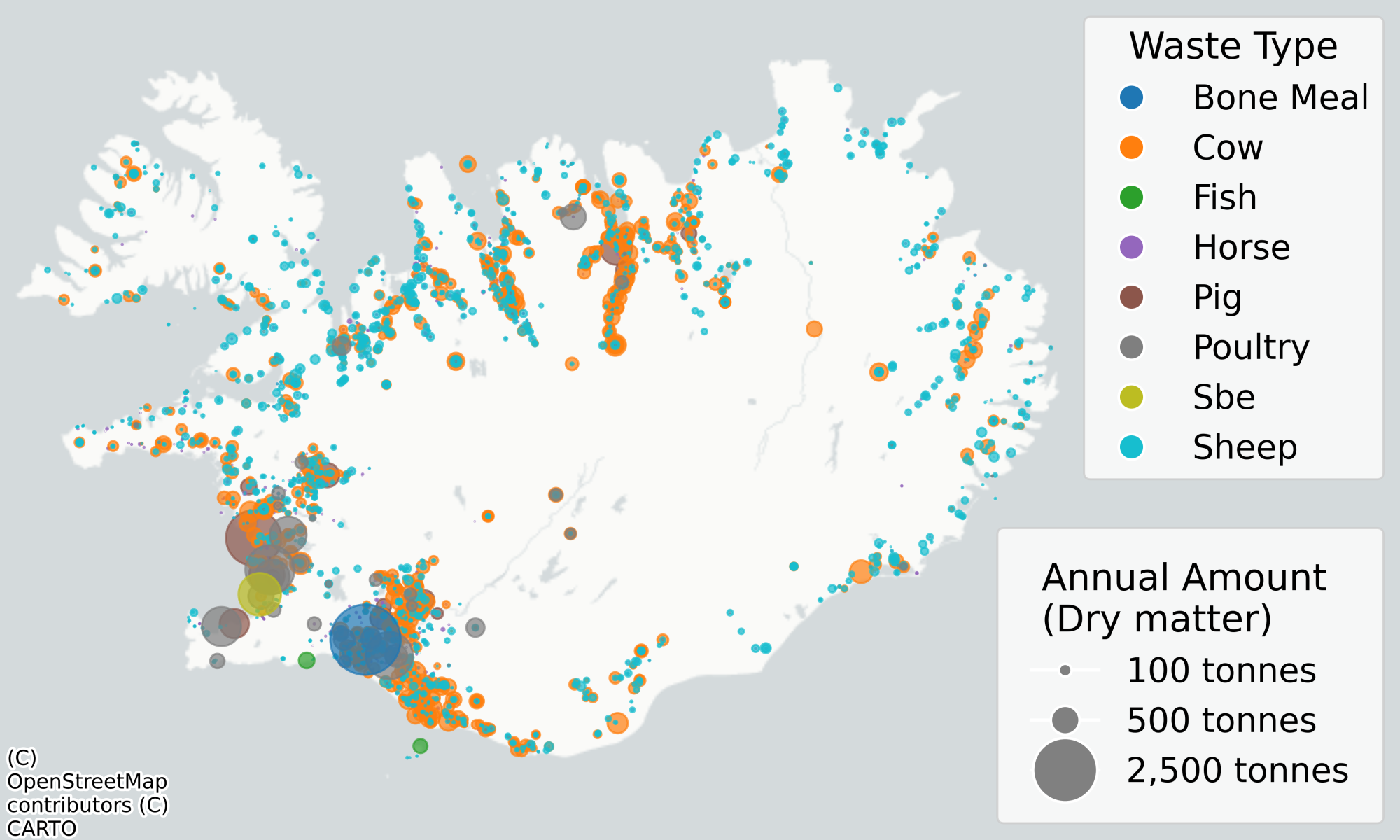

Mapping Iceland’s organic Resources

Before waste could become energy, it had to be located and quantified. Teams under Terraforming LIFE conducted GPS-based mapping of farms and waste producers across the nation. The results revealed significant concentrations of organic material in specific agricultural regions, allowing researchers to pinpoint optimal sites for future biogas plants.

Preliminary analyses of manure and fish sludge have already provided key data: dry-matter content, nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium (N-P-K) ratios, and salinity levels. Early calculations of biogas yield are promising, confirming that Iceland’s combined organic waste streams could fuel a small but meaningful renewable-energy sector.

Challenges on the horizon

Despite the progress, several challenges remain. Regulatory barriers are among the most pressing: under current Icelandic regulations, fish sludge cannot be used as fertiliser on grasslands. This restriction limits one of the most promising circular uses of organic waste. Work is already underway with the Icelandic Food and Veterinary Authority (MAST), which is the Competent Authority (CA) in Iceland for fertilisers, to address this issue.

In parallel, Iceland still lacks a dedicated biogas-testing laboratory, which complicates experimentation with new feedstock combinations and the optimisation of reactor conditions. A feasibility study is in progress to determine whether such a facility should be established domestically or whether samples should continue to be exported for analysis abroad.

Logistics also pose a challenge. Remote farms and widely dispersed aquaculture sites make waste collection and transport costly and complex. Finally, beyond technical and regulatory hurdles, social acceptance remains essential. Building community trust in biogas infrastructure requires transparency, clear communication, and active collaboration with end-users – especially the farmers who will ultimately benefit from the resulting fertiliser.

Next steps to turn waste-to-value

As Terraforming LIFE moves into its next phase, the focus shifts from research to implementation. Key priorities include:

- Completing sludge-dewatering installations at the First Water site.

- Finalising an environmental-impact assessment and plant design.

- Advancing regulatory work to enable the safe use of fertiliser from fish sludge on grassland.

- Conducting biogas experiments – either domestically or through international partners.

- Continuing a structured engagement campaign to strengthen social trust.

Each milestone brings Iceland closer to an integrated circular-economy system – one capable of converting thousands of tonnes of organic waste into valuable resources each year.

Toward a circular Iceland

The promise of Terraforming LIFE extends far beyond waste management. It embodies a vision of self-reliance – transforming what was once discarded into clean energy, fertiliser, and opportunity. By linking the aquaculture and agricultural sectors, the project demonstrates how innovation can enable nutrient reuse, reduce waste disposal, lower carbon footprint, enhance farmers’ operational security and strengthen Iceland’s food security.

If successful, Terraforming LIFE could serve as a blueprint for circular economies worldwide, demonstrating how even the smallest nations can transform organic waste into valuable resources.