A Stanford-led phase 3 trial shows gene therapy skin grafts significantly heal chronic wounds in patients with severe epidermolysis bullosa, reducing pain and improving quality of life

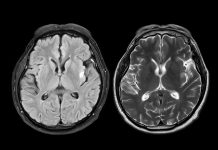

Epidermolysis bullosa is the name for a group of rare inherited skin disorders that cause the skin to become very fragile; even the slightest touch can cause blistering. The condition is usually diagnosed in babies and young children, as symptoms can be evident from birth.

Now, new research from Stanford Medicine offers new hope for patients with severe dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, as a clinical trial shows that gene therapy skin grafts can safely and effectively heal chronic wounds. The results are published in The Lancet, and the skin grafts were approved as a therapy by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on April 29.

Genetically engineered grafts improve healing and reduce itching

The skin grafts, developed by Stanford researchers, utilise the patient’s cells to heal persistent wounds in patients with epidermolysis bullosa, a condition often referred to as “butterfly skin.”

This new treatment is part of a larger effort to improve epidermolysis bullosa therapy options. Another recent treatment recommendation is a gene therapy gel that helps prevent and heal more minor wounds. However, patients still need an effective treatment for larger, more persistent wounds, and skin grafts meet this need.

“With our novel gene therapy technique, we successfully treated the hardest-to-heal wounds, which were usually also the most painful ones for these patients,” said the study’s lead author, Jean Tang, MD, PhD, a professor of dermatology who treats children with EB at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford. “It’s a dream come true for all the scientists, physicians, nurses and patients who were involved in the long and difficult research process.”

“Collagen VII is like a staple that attaches the top layer to the bottom layer of your skin,“ Tang said. Without this molecular “staple,“ the layers of patients’ skin separate in response to slight friction, even a light touch. This causes wounds that can persist for years, as well as extreme pain and itching.

“These kids are wrapped in wound dressings almost from head to toe, just to protect their delicate skin,“ Tang said. “They’re known as butterfly children because their skin is as fragile as butterfly wings.”

Over 20 years of research into epidermolysis bullosa

Stanford Medicine research teams began conducting studies on epidermolysis bullosa in the early 2000s. They began research showing that a corrected gene could be engineered into skin cells, that the engineered skin grafts would function in a mouse model of the disease, and that the grafts are safe and effective for people with epidermolysis bullosa.

In 2003, Dr. Paul Khavari and Dr. Zurab Siprashvili developed a safe method to genetically correct epidermolysis bullosa (EB) skin cells, demonstrating that they could grow small patches with functioning collagen VII suitable for grafting onto mice. This research led to Stanford Medicine studies on gene therapy skin grafts for humans, including a phase 1 clinical trial conducted by Dr. Alfred Lane and Dr. Peter Marinkovich, which showed early signs of safety and effectiveness and was published in 2016.

The researchers created the skin grafts using a small biopsy of the patient’s unwounded skin. The biopsy is taken to a lab, where a retrovirus is used to introduce a corrected version of the COL7A1 gene, which encodes collagen VII, to the skin cells. The genetically engineered cells are grown into sheets of skin and are prepared for 25 days. A plastic surgeon sutures the genetically engineered skin onto a wound. As each graft is designed using the patient’s skin, the treatment provides healthy skin that matches the patient’s immune markers, thereby preventing graft rejection.

The phase 3 study included 11 patients aged at least six years old with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. The study compared pairs of wounds in similar locations on the same person: One wound from each pair was treated with a genetically engineered skin graft, and the other was treated with usual care practices. Each patient could contribute multiple pairs of wounds; the study ultimately included 43 wound pairs.

After the grafts were applied, the researchers monitored wound healing, pain and itching at regular intervals over about six months. At 24 weeks after grafting, 81% of treated wounds were at least half healed, compared with 16% of control wounds. At the same time point, 65% of treated wounds were at least three-quarters healed, compared with 7% of control wounds, and 16% of treated wounds had healed entirely, compared with none of the control wounds. In addition, patients’ reports of pain, itching, and blistering were better in the grafted areas than in the control wounds, showing more improvement from baseline.