Scientists at UCL and GOSH have used groundbreaking base-edited CAR‑T cell therapy — BE‑CAR7 — to treat aggressive T‑cell leukaemia, with two‑thirds of patients now disease‑free

A new “living‑drug” gene therapy developed at UCL and Great Ormond Street Hospital has successfully put aggressive, previously incurable T‑cell leukaemia into remission. The base‑edited CAR‑T cell treatment, BE‑CAR7, reprogrammes donor immune cells to target and destroy cancerous T‑cells. In early trial results, around 64% of treated patients are disease-free at follow-up, and overall, 82% achieved deep remission following BE-CAR7, enabling them to proceed to stem cell transplant without detectable cancer. These results offer a potentially life-changing option for patients previously considered beyond help.

The trial’s findings are published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Groundbreaking gene therapy delivers lasting results for blood cancer patients

BE-CAR7 was designed by a research team led by Professor Waseem Qasim (UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health) as the first in-human application of base-edited cells.

The study dates back to 2022, when a 13-year-old called Alyssa Tapley, from Leicestershire, became the first person in the world to receive the treatment as part of a clinical trial at GOSH. Doctors had trialled all other available treatments without luck.

Following Alyssa’s landmark case, eight more children and two adults have undergone the treatment as part of the trial.

Key findings from the trial include:

- 82% of patients achieved very deep remissions after BE-CAR7, allowing the participants to proceed to stem cell transplant without disease.

- 64% remain disease-free, with the first patients being three years disease-free and off treatment,

- Expected side effects were tolerable, with the greatest risks arising from virus infections until immunity recovered.

Professor Qasim, a Professor of Cell and Gene Therapy at UCL, who led the research, said: “A few years ago this would have been science fiction. Now we can take white blood cells from a healthy donor, change a single letter of their DNA code, and give them back to patients to try to tackle this hard-to-treat leukaemia.

“We designed and developed the treatment from lab to clinic and are now trialling it on children from across the UK – in a unique bench-to-bedside approach.”

Alyssa, now aged 16, who has a brother, said: “It is incredible how much my life has changed. I went from four months straight in GOSH to now only coming back for medical appointments once a year. It is amazing how much freedom I have now.

“I am really grateful for all the opportunities the gene therapy treatment has given me. I feel like I have been able to help everyone else who went on the clinical trial after me.

“I’ve now been able to do some of the things I thought earlier in my life would be impossible for me to do. I really did think I was going to die and that I wouldn’t be able to grow up and do everything that every child deserves to be able to do.”

“I’ve now been able to do some of the things I thought earlier in my life would be impossible for me to do. I really did think I was going to die and that I wouldn’t be able to grow up and do everything that every child deserves to be able to do.”

How BE‑CAR7 works: base‑edited CAR-T cells offer hope for children with T-cell leukaemia

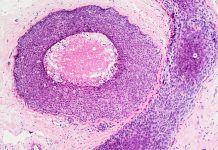

To provide further context, CAR-T cell immunotherapy currently treats several types of blood cancer. Using T cells, the therapy modifies them to express specific proteins on their surfaces called chimeric antigen receptors (CARs).

These CARs can recognise and target specific ‘flags’ on the surface of cancer cells, enabling T cells to destroy those cancer cells. However, developing a CAR-T cell therapy for leukaemia has been challenging.

BE-CAR7 T-cells are engineered using base editing, which aims to reduce the risk of chromosomal damage.

The researchers used CRISPR to change single DNA letters in T-cells, creating universal CAR-T cells that can attack T-cell leukaemia in patients.

Universal CAR T-cells were made from a healthy donor’s white blood cells using an automated process with custom-made RNA, mRNA, and a lentiviral vector developed by the team.

Professor Qasim added: “Many teams were involved across the hospital & university, and everyone is delighted for patients clearing their disease, but at the same time, deeply mindful that outcomes were not as hoped for some children. These are intense and difficult treatments – patients and families have been generous in recognising the importance of learning as much as possible from each experience.”

Dr Rob Chiesa, Study investigator and Bone Marrow Transplant consultant at GOSH, said: “Although most children with T-cell leukaemia will respond well to standard treatments, around 20% may not. It’s these patients who desperately need better options, and this research provides hope for a better prognosis for everyone diagnosed with this rare but aggressive form of blood cancer.

“Seeing Alyssa go from strength to strength is incredible and a testament to her tenacity and the dedication of an array of a small army of people at GOSH. Team working between bone marrow transplant, haematology, ward staff, teachers, play workers, physiotherapists, lab and research teams, among others, is essential for supporting our patients.”

Dr Deborah Yallop, consultant Haematologist at KCH, said “We’ve seen impressive responses in clearing leukaemia that seemed incurable – it’s a very powerful approach.”