An investigational gene therapy has restored immune function in all nine children with severe leukocyte adhesion deficiency-I, a rare immune disorder

A new trial, led by UCL, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children (GOSH), Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús in Madrid, and UCLA, involved nine children aged five months to nine years with severe leukocyte adhesion deficiency I (LAD-I) and tested the effects of gene therapy on the rare immune disorder.

The research is published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

LAD-I: A rare but fatal immune disease

LAD-I is a rare immune disorder in which children do not have a functioning immune system and are constantly struggling to fight infections. These children are frequently hospitalised and, without treatment, rarely live past two years old.

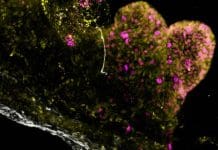

The rare immune disorder is caused by genetic variants in the gene responsible for the production of CD18. CD18 is a protein on the surface of white blood cells that allows them to get out of the bloodstream and to the site of an infection.

In healthy people, once white blood cells reach a site of infection, they can tackle it without much concern. However, for children with severe LAD-I, the faulty white blood cells can’t get to where they are needed, leaving the children vulnerable to frequent and escalating infections.

The standard treatment is a bone marrow transplant to provide stem cells from a donor with the correct genetic code to create white blood cells with CD18. However, this process can be lengthy, as finding a matching donor can be difficult. Even if this treatment is successful, a bone marrow transplant can have serious and life-threatening side effects, like the rejection of donor cells and graft-versus-host disease, where the donated cells attack the recipient’s body.

The gene therapy uses the patient’s stem cells

The new gene therapy research involves clinicians taking the patient’s stem cells and modifying them with a gene therapy that instructs the cells to create the missing protein needed to get out of the bloodstream and fight infection. The corrected cells are then returned to the patients, where they can develop a working immune system.

Using the patient’s stem cells avoids the risk of rejection or graft-versus-host disease.

The researchers found that all nine children responded well to the treatment and, after one to two years of treatment, survived with fewer symptoms. Their skin and dental lesions, infections, and inflammatory symptoms have resolved, and the children have resumed a relatively normal life.

After treatment, the children had their blood analysed and were found to have the CD18 protein needed to fight infections long term, allowing them to stop taking their previous medications for the rare immune disorder.

Professor Claire Booth (UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health and GOSH) said: “We are thrilled for Eisa and all the children in this trial but also because this success has far-reaching implications, beyond severe LAD-I.

“As this process has been shown to be successful for such a complex disease, we could move towards a blueprint to treat many other diseases. Gene therapy is being explored by teams at GOSH and our partners for blinding conditions, muscular dystrophies, cancer, and others – the possibilities are really far-reaching.”

Study co-author, Dr Donald Kohn (UCLA) said: “Seeing our patients in three different countries, offered a chance at childhood without serious infections and without frequent hospital visits, is a testament to how beneficial this therapy could be.”

Dr Julian Sevilla (Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús) said: “This trial demonstrates once again how gene therapy could potentially cure diseases that would otherwise be incurable without adequate stem cell donors, with shorter hospital stays and fewer adverse side effects.”