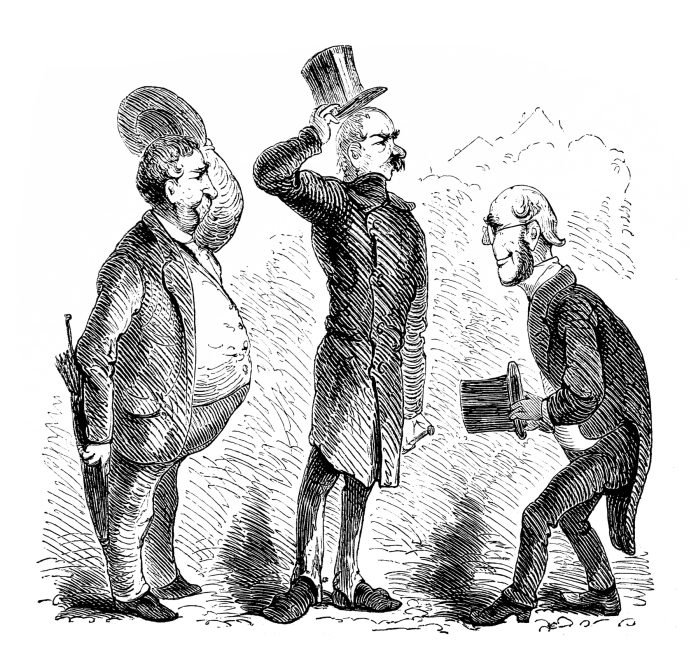

The traditional courtly bow and removal of the hat was not a manoeuvre to be undertaken rapidly or casually. Instead, it was undertaken slowly – and, ideally, with almost balletic agility

‘making a leg’, bowing deeply from the waist,

and removing his hat.

A gentleman in the ceremonial presence of a great lord or a king would approach the target of his reverence and look directly (though not in any way aggressively) at the king or lord. The next stage was to slowly extend one leg forward (usually the right leg), in the direction of the person to whom homage was being paid. Then, as the leg slid forward, the upper torso would bend forward slowly and gracefully, while the hat was simultaneously removed with one hand (often the right hand) and lowered with a flourish. The deep bow would then be sustained for a notable moment before the gentleman slowly resumed an upright stance.

Hat honour

This ritual was known as ‘hat honour’. The principle behind it was that the head was taken to represent the individual person. Therefore, the one who held his head high, whilst still wearing his hat, and then received homage from others, had manifestly the ‘highest’ status. But the one who lowered his head – and not only his head but his hat as well – was visibly acknowledging his status as the ‘lower’ of the two.

Having removed the hat, the gentleman would then tuck his headgear under his arm, whilst still in the presence of the king. This degree of civility was required on formal occasions at court or other ceremonial meetings. The monarch, meanwhile, would acknowledge the salutation with an affable smile and perhaps a very slight inclination of the head in return.

For his part, the gentleman would not feel that his own dignity had been in any way compromised. Instead, he was accepting his own role in a hierarchical society which was subdivided into very many social ‘orders and degrees’. Therefore, when the gentleman in turn went about his own business, he himself would often be the highest-ranked person in any given company. So he would expect other ‘lower’-ranked men to bow their heads and to doff their caps to him. And he, in turn, would nod graciously in reply.

Generally, men among the ‘lower orders’ of society would not undertake the full courtly ritual of ‘making a leg’. But they would be expected to perform their ‘hat honour’ with proper respect and with total gravity. These were quiet social signals, indicating that all knew and understood their place in the world.

Status complications and controversy

One amusing complication arose when people of different ranks drew physically fairly close to one another but were not actually intending to meet. If a king or another high-ranking person was strolling abroad in a London park, for example, how near did those of ‘lower’ status have to be to salute him formally?

That dilemma once confronted the diarist Samuel Pepys in 1667. He was himself strolling idly in London’s Hyde Park when he saw – at some distance away – the Duke of York, also taking the air. Not only was the Duke of York a royal prince and brother of King Charles II, but he was also Admiral of the Navy, for whose administrative Board Samuel Pepys served as secretary. He therefore owed double duty to a royal prince and his ultimate employer.

Yet the Duke and the diarist were not walking together. Pepys accordingly fretted about the problem that he faced. If the Duke saw him, and he was making ‘hat honour’ from too far away, he might look foolishly obsequious. On the other hand, if the Duke did spot Pepys and thought he was near enough to offer a salutation, then if Pepys remained hatted, he might seem to be snubbing his princely employer. How far did the zone of respect extend around a social bigwig? There were no precise rules.

Such anxious considerations kept everyone mentally alert. When people met, outside those formal occasions when the requirements of polite etiquette were clear, they had to decide for themselves, in a process of unofficial social negotiation. How to greet one another, without appearing either too slavish or too rude? And what’s more, such decisions had to be made swiftly.

Moreover, on some rare occasions, there were direct confrontations over the performance of ‘hat honour’. One instance concerned an oatmeal-maker (an artisan of no more than ‘middling’ social status) who was preaching unofficially but very publicly – to spread his ultra-radical Protestant beliefs.

In April 1630, the radical oatmeal maker was apprehended and brought before the Court of High Commission—a body appointed by the royal authority of King Charles I to enforce church discipline. A witness account recorded that, to general shock, the oatmeal-maker refused to remove his hat before this august company of senior churchmen. He explained that he did not accept the authority of the Bishops. There should, in his view, be no church intermediaries between God and his true believers.

But one person present objected. He pointed out that the Commissioners were also members of the King’s Privy Council. Would not the oatmeal-maker take off his hat to acknowledge the secular authority of the King’s ministers?

Instantly, the radical artisan doffed his hat. But, just as quickly, he then restored it. His reason? The eye-witness reporter quoted him as stating sturdily: ‘As you are Privy Councillors, I put off my hat; but as ye are rags of the Beast [agents of the Devil], lo! – I put it on again. He accordingly stood his ground.

Confrontations such as that one indicated that not all Britons were prepared to accept old traditions unthinkingly. And indeed, over time, the formalities of traditional ‘hat honour’ were becoming reserved for formal occasions, like court presentations.

Handshaking

Gradually, the handshake was beginning to gain use as an alternative form of daily greeting. Shaking hands did not, in itself, introduce social equality (nor was the gesture intended to do anything as radical as that). It was, however, increasingly adopted as an egalitarian greeting – for example by merchants and traders – and by radical Protestant groups such as the Quakers (founded in 1656). These hand-shaking individuals were accepting one another as fellow citizens, who were equal at the point of salutation. Many others might still bow and remove their hats in the presence of the monarch. However, society was diversifying, and greetings were doing the same.

‘Hat honour’ has not entirely disappeared – though the ritual of ‘making a leg’ has done. Thus, men may still remove their hats as a sign of respect, for example, in church, at funerals, and when meeting grandees. Furthermore, polite gentlemen may also doff their hats and bow lightly to salute ladies. Old traditions do often die hard.

Nevertheless, in society today, when many men regularly go out bare-headed, ‘hat honour’ is no longer a necessity but a personal option. And an increasingly old-fashioned one at that!

For further information:

See Penelope J. Corfield, ‘Dress for Deference and Dissent: Hats and the Decline of Hat Honour’, in journal Costume, 23 (1989), pp. 64-79; also published in German translation in K. Gerteis (ed.), Zum Wandel von Zeremoniell und Gesellschaftsritualen in der Zeit des Aufklärung, special edn. of Aufklärung, 6 (1991), pp. 5-18; and available on PJC website: www.penelopejcorfield.com/British-history/3.2.2 (Pdf/8).