Research from The University of Edinburgh has found that almost two-thirds more people are living with ME/CFS in England than previously recorded

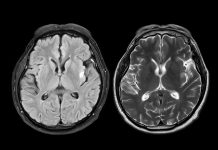

ME/CFS (myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome) is a long-term condition that affects different parts of the body, with the most common symptom being extreme tiredness. This condition has no treatment and no single diagnostic test.

It was previously accepted that 250,000 people were affected by this condition; however, a new estimate suggests that approximately 404,000 people are affected by ME/CFS.

Researchers used data from over 62 million people in England

Researchers from the University of Edinburgh used NHS data from more than 62 million people in England to identify those diagnosed with ME/CFS or post-viral fatigue syndrome. They examined the data by gender, age, and ethnicity, and grouped it by different areas of England.

The study found that the lifetime prevalence of ME/CFS for the population of women and men in England may be as high as 0.92% and 0.25%, respectively, or approximately 404,000 people overall.

Prevalence of ME/CFS varied widely across England, with Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly having the highest rates, while North West and North East London reported the lowest. The condition peaked at around 50 for women and 60 for men, with women six times more likely to have it than men in middle age.

ME/CFS diagnosis varies by ethnicity

The research found that ME/CFS prevalence varies greatly by ethnicity. For example, white people are almost five times more likely to be diagnosed than those from other ethnic groups.

Furthermore, the researchers saw this discrepancy across all regions for both women and men. People of Chinese, Asian/Asian British, and black/black British backgrounds are significantly less likely to be diagnosed with ME/CFS, with rates 65% to 90% lower than white people. The difference is more pronounced than for other conditions like dementia or depression, experts say.

Improved medical training and research into accurate diagnostic tests are needed to address current gaps in ME/CFS care. While there is no cure, a diagnosis remains valuable—it helps validate patients’ experiences, strengthens relationships with healthcare providers, supports symptom management, enables access to disability benefits, aids in clinical trial participation, and connects patients to supportive communities.

“The NHS data shows that getting a diagnosis of ME/CFS in England is a lottery, depending on where you live and your ethnicity. There are nearly 200 GP practices – mostly in deprived areas of the country – that have no recorded ME/CFS patients at all. The data backs up what many people with ME/CFS say: that they feel invisible and ignored,” commented Professor Chris Ponting of the MRC Human Genetics Unit at the University of Edinburgh’s Institute of Genetics and Cancer.

“People struggle to get diagnosed with ME/CFS. Diagnosis is important, because it validates their symptoms and enables them to receive recognition and support. Our results should now lead to improved training of medical professionals and further research into accurate diagnostic tests,” added Gemma Samms, ME Research UK-funded PhD student.

The study is published in the medical journal BMC Public Health. It was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research, the Medical Research Council and the charity ME Research UK.