Contributors from the PKU community, including patient reps, key opinion leaders, and medical experts, discuss the implications of redefining ‘unmet medical need’ in the EU’s pharmaceutical legislation, emphasising the potential negative impact on patients, particularly those with rare diseases like phenylketonuria

How we define ‘unmet medical need’ (UMN) shapes the future treatment options for millions of patients. These definitions have a profound impact on which patients receive new treatments, which conditions attract research funding, and which communities are told their suffering is not severe enough to deserve intervention.

As EU and national policymakers in Brussels revise the legislative framework for pharmaceuticals in the EU (the ‘General Pharmaceutical Legislation’ (GPL)), they are debating whether to shift from the previous broad definition of UMN to a narrower, criteria-based definition focusing on the clinical concepts of high morbidity and mortality.

Redefining UMN in Europe will have far-reaching consequences

UMN classification determines eligibility for regulatory incentives, such as extended market exclusivity or priority review. It often influences whether national authorities consider a treatment cost-effective and eligible for public healthcare coverage. A narrower definition could create a two-tier system in which certain diseases attract investment and policy attention while others, despite substantial patient needs, are neglected. In countries with tighter healthcare budgets, the absence of UMN designation could further restrict access to essential treatments, deepening their disparities in access with well-funded healthcare systems. Already today, developers could be looking at the move and deciding to pause investing in medicines that are no longer considered to be meeting an unmet need. Once adopted, it will also shape innovation and policy discussions beyond the EU’s borders. Such classification risks locking patients into outdated, burdensome treatment models while innovation shifts toward diseases with no existing options, leaving those with so-called ‘treatments’ still facing significant unmet needs.

How the Commission’s proposal falls short

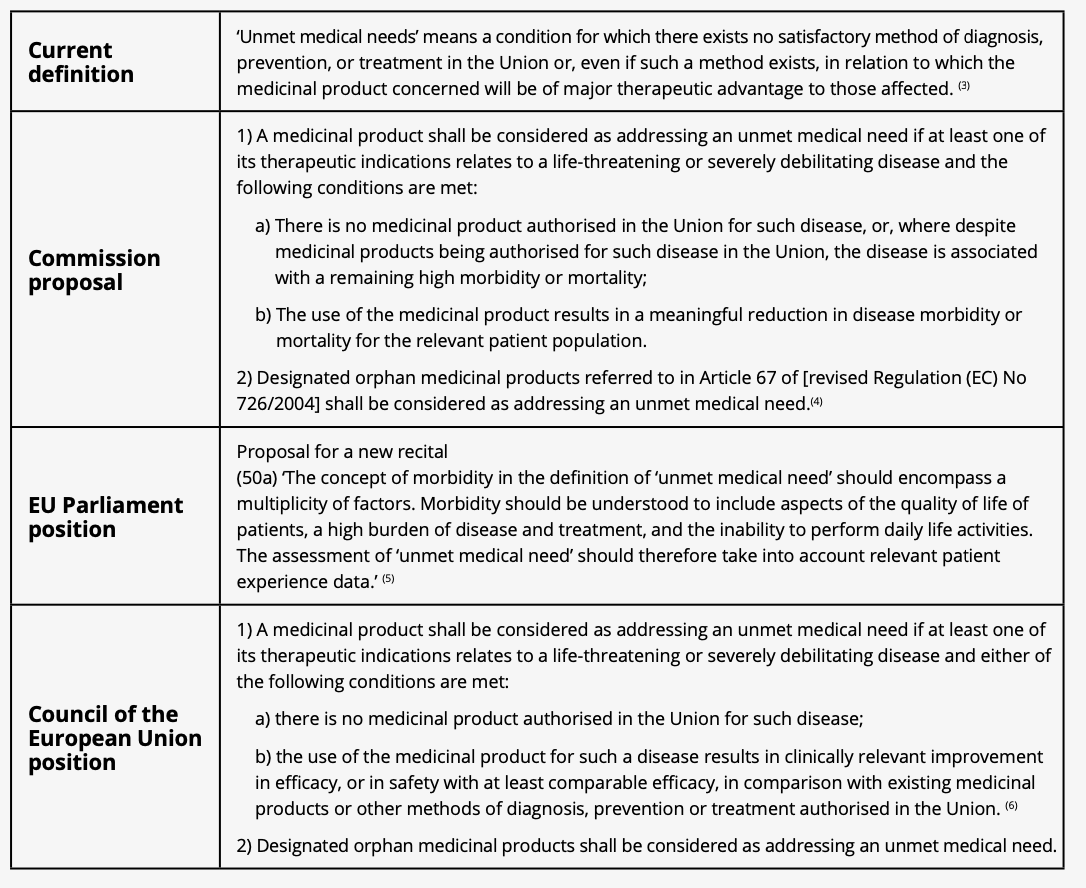

Proposed definitions of unmet medical need ahead of trilogue negotiations

The EU Commission’s proposal, published in April 2023, suggests that a disease will be classified as having an unmet medical need only if it is ‘life-threatening or severely debilitating’ and has either no existing treatment or high morbidity/mortality despite treatment.

At first glance, prioritising conditions with the highest clinical severity seems logical. However, it fundamentally overlooks the realities of many rare diseases, where disease and treatment burdens remain high despite existing therapies.

Phenylketonuria (PKU) is a clear example of how a narrow UMN definition fails to reflect real-world patient needs

PKU is a rare, inherited metabolic disorder requiring lifelong, intensive management to prevent severe cognitive, psychological, and developmental complications. While early diagnosis and dietary treatment have reduced mortality, care remains highly restrictive, with many patients struggling to maintain effective blood-Phe control over time. The PKU diet is relentless. Patients must meticulously measure food items at every meal, avoiding most natural protein food sources. It is an exhausting, daily battle with dietary treatment affecting almost every aspect of life. PKU treatment has changed little since the 1960s, leaving patients and caregivers encumbered by rigid diets, causing social isolation, and ultimately leading to lifelong psychological harm to individuals.

We believe PKU is representative of a new paradigm for many rare diseases, where although standards of care exist, they are outdated, under-researched, and intolerable as patients age. Dietary treatment has reduced morbidity, yet patients still face lifelong cognitive, psychological, and social challenges. Under the Commission’s proposal, however, PKU and similar conditions risk wrongly being perceived as ‘solved’ – potentially stalling progress on better treatments.

Other definitions are available

The EU is not defining UMN from scratch: it already has an existing definition. Until now, UMN has been defined broadly as any condition for which ‘no satisfactory method of diagnosis, prevention, or treatment exists’ or where a new treatment provides a ‘major therapeutic advantage.’ Alongside other policy measures like the Orphan Drug Regulation, this definition has contributed to greater investment in rare diseases and helped bring orphan drugs to market.

Most concerns about this definition centre on its being too broad in scope. The Commission and Member States’ aim, therefore, is to ensure incentives are more precisely targeted at treatments that deliver genuinely transformative benefits for patients. This a legitimate objective, but it’s worth noting that other regulatory agencies have faced similar challenges and have sought to refine frameworks rather than significantly narrow eligibility.

The US FDA, Health Canada, and Australia’s TGA take a more flexible approach, recognising that the presence of an existing therapy does not eliminate UMN. More recently, as part of Belgium’s 2024 EU Council Presidency, its Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE) developed a ‘NEED framework’ (1) that aims to provide a structured, multidimensional approach to identifying UMN and ensuring a patient-centric assessment of disease burden.

In our recent publication for the European Society for Phenylketonuria and Allied Disorders Treated as Phenylketonuria (2) (E.S.PKU) ‘Capturing the Full Picture: A Joint Policy Paper on Unmet Medical Need in Phenylketonuria,’ we used the Belgian health authority’s NEED framework of health-, healthcare- and broader social-related needs, to present the lived experiences of PKU patients, their families and caregivers and set out the various, and significant, burdens that remain.

Recognising that UMN definitions play a crucial role in funding and policy decisions, it is essential that any definition include criteria beyond clinical outcomes to capture the full picture of the lived realities of patients and their caregivers, ensuring our patients are not left behind. We call on European decision-makers to include in the GPL:

- A broad definition of UMN that fully captures the impact on patients, families, and caregivers, including treatment burden and quality of life. The definition of UMN should include an explicit statement that the concept of morbidity in the definition of UMN should be understood to include aspects of quality of life of patients, a high burden of disease and treatment, and the inability to perform daily life activities. It should therefore take into account relevant patient experience data.

- The systematic and meaningful involvement of patient voices and clinical experts in UMN assessments.

- Explicit recognition of UMN definition limitations to prevent unintended consequences, such as removing incentives to develop treatments for conditions wrongly perceived as ‘solved.’

References

- C.M. De NoordHout, M. Levy, R. Claerman, M de Jaeger et al., NEED: Assessment of the Unmet Needs of Patients and Society, KCE Report 377Cs, 2024

- The European Society for Phenylketonuria and Allied Disorders Treated as Phenylketonuria (E.S.PKU) represents not only individuals with PKU, but also those with related metabolic disorders managed through similar dietary strategies. These include conditions such as tyrosinemia type 1 (TT1), organic acidurias, urea cycle defects, homocystinuria (HCY), pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy (PDE), and lysinuric protein intolerance (LPI).

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EC) No 507/2006 of 29 March 2006 on the Conditional Marketing Authorisation for Medicinal Products for Human Use Falling Within the Scope of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council. OJ 2006; L92:6–9.

- European Commission’s Proposal Directive relating to medicinal products for human use (Com (2023) 192 final 2023/0132 (COD)), art. 83.

- European Parliament, Report on the proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Union code relating to medicinal products for human use, and repealing Directive 2001/83/EC and Directive 2009/35/EC, (COM (2023)0192 – C9 0143/2023 – 2023/0132(COD)), Amendment 34, Proposal for a directive, Recital 50 a (new).

- Council of the European Union. Interinstitutional Files: 2023/0132(COD); 9285/25. 2 June 2025. Chap VII, art. 83, pp. 162-163.