Eradicating malaria will not be easy or cheap, but it will be worthwhile in the long run, argues Professor David H Peyton of Portland State University

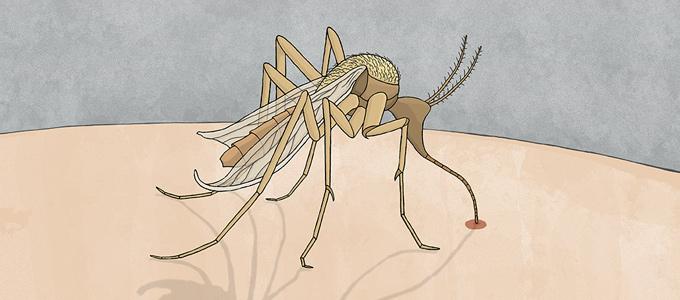

Malaria is several things: A group of related parasites, an infectious disease that is transmitted by mosquitoes (if you are a human) or by humans (if you are a mosquito), as well as a public health situation, a crisis, or a disaster (depending on who you are).

If you have been infected by malaria on a number of occasions, it can give you flu-like symptoms. However, if you are a visitor to a malaria-endemic region and did not take the preventative medicine, or a child who lives there and does not have a well-developed immune system, malaria could result in death. Or perhaps malaria seems not to touch you at all.

Partly because of the large number of parasites that develop during an infection, and their short life-cycle, the malaria parasite evolves efficiently, and so it develops resistance to all the tools (including the insecticides, drugs, vaccines) we bring to bear against it. Without some serious self-assessment, we might end up not solving the issue of malaria. And we need to.

Malaria is still a major killer

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recently published its World Malaria Report 2016. This document is worthy of study for anyone trying to understand the issues behind the various worldwide programmes in malaria control.

The World Malaria Report 2015 reports that the total number of malaria deaths were 429,000 (range: 235,000-639,000) in 2014. The World Malaria Report 2016 gives the total malaria deaths as 438,000 in 2015 (range: 236,000-635,000). Another statistic from the World Malaria Report 2016 is that:

“In 2015, 303,000 malaria deaths (range: 165,000-450,000) are estimated to have occurred in children aged under 5 years, which is equivalent to 70% of the global total. The number of malaria deaths in children is estimated to have decreased by 29% since 2010, but malaria remains a major killer of children, taking the life of a child every 2 minutes.” Is this enough progress?

In response to such challenges, another report has been formulated, the ‘Global Technical Strategy for Malaria 2016-2030‘ (or GTS). Quoting from this document: “To achieve the milestones and goals set out in this strategy, malaria investments, including both international and domestic contributions, need to increase substantially above the current annual spending of US $2.7 billion. The annual investment will need to increase to an estimated total of US$ 6.4billion per year by 2020 to meet the first milestone of 40% reduction in malaria incidence and mortality rates.”

These are not goals that are to be ‘hoped for’. Rather, these are guides for what was projected in order to achieve the target of 90% reduction in malaria over the course of 15 years.

The latter stages of the malaria elimination game

Beyond these observations is the simple fact that some initial successes may breed complacency. Will we maintain the will to move beyond control measures into elimination strategies (in regions), in order to achieve eventual global eradication? Or will we lose focus as the rates of malaria infections and deaths drop to levels that seem insignificant?

The perverse truth here is that low transmission settings have special challenges, so the disease won’t necessarily go quietly and easily as we enter the final phases. Failure at the latter stages of the malaria elimination game would mean that the parasites would have the opportunity to infect large populations with naive immune systems. This is no theoretical speculation: We have the history of the failed campaigns of the 1960s and 1970s to look back upon.

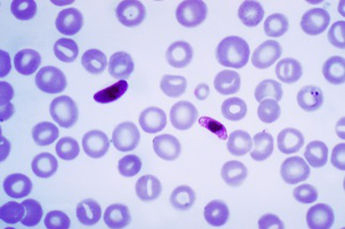

Plasmodium falciparum, the malaria parasite. Source: CDC/Dr Mae Melvin

What I’m suggesting here is that a commitment to eradicate malaria is just that: A commitment. It is a commitment to do whatever it takes, for as long as it takes, regardless of geographical and political boundaries. Eradication of malaria will probably require at least three decades. This effort will not be easy; it will not be inexpensive; it will almost certainly be met with setbacks. We will need new tools, both in the current pipeline and yet to be conceived.

Overcoming drug resistance

The good news is that scientific progress is presenting great possibilities, but the bad news is the significant winnowing process between scientific promise and pay-off. Likewise, the lag-time between, say, a new drug lead and a drug that can be given to patients can be a decade or more. But the work will be worthwhile, because not to do so will be to live with a parasite that continues to evolve, and renders each generation of tools less useful. The microorganism always wins – as long as it survives.

After spending about half of my career on other scientific endeavours, I moved into working on infectious diseases, including malaria. That move was a career risk, but I thought that malaria was important. Since then, my team have been working on a drug approach that is specifically targeted at overcoming the parasite’s drug resistance, and extending that approach to other microbial diseases.

It is also important that we tell the truth: elimination won’t be easy. To ignore these issues is to set ourselves up for disappointment and for far worse challenges and expenses as the parasite evolves into something that we have not yet confronted.

David H Peyton, PhD

Portland State University

Tel: +1 503 725 3875

Please note: this is a commercial profile