A plan to cut carbon emissions in China: A forty-year project to green the Taklamakan Desert’s edge has successfully created a measurable carbon sink.

Research from the University of California, Riverside, shows that these hardy shrubs effectively pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere

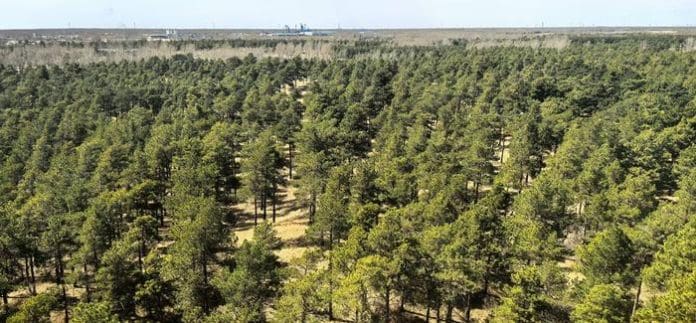

A forty-year effort to stabilise the edges of the Taklamakan Desert in western China has successfully created a measurable carbon sink. A recent study led by researchers at the University of California, Riverside (UCR) confirms that planting hardy shrubs on previously barren land, a process known as afforestation, can effectively pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere even in extremely arid environments.

The project began in 1978 when the Chinese government initiated large-scale planting to halt desert expansion. Today, satellite data reveals that these efforts have transformed the desert rim into a thriving shrubland similar to the chaparral found in Southern California.

Measuring the green shift and tracking carbon emissions in China

The research team, which included scientists from the University of Houston, Tsinghua University, and Caltech, utilised data from NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory and the MODIS satellite.

They focused on two primary indicators of success:

- A decrease in atmospheric carbon dioxide

- An increase in solar-induced fluorescence.

The latter is a faint light emitted during photosynthesis that serves as a proxy for plant productivity.

Satellite readings identified a “cold spot” over the treated areas, where carbon dioxide concentrations were 1 to 2 parts per million lower than surrounding regions. King-Fai Li, a UCR atmospheric physicist and co-author of the study, noted that the ability to verify this drawdown from space provides a positive, measurable metric for the project’s impact.

Political and environmental context: Cutting carbon emissions as a nation

The Taklamakan project has persisted for decades due to a level of political stability that similar international efforts, such as those in the Sahara, have often lacked. China’s motivations for the project were multifaceted.

Rapid desertification threatened valuable farmland and contributed to regional instability in western China, an area where minority ethnic groups and Han Chinese leadership have historically seen tension. By taming the desert, the government aimed to secure agricultural land while simultaneously addressing the nation’s carbon footprint.

Scope and limitations of afforestation

Despite the success of the project, the researchers urge a realistic perspective on its global impact. The Taklamakan Desert is roughly the size of Germany, spanning approximately 337,000 square kilometres.

The study suggests that even if the entire desert were covered in shrubs, it would sequester about 60 million tons of carbon dioxide annually. This amount represents only 10% of Canada’s annual emissions and is a small fraction of the 40 billion tons produced each year globally.

The primary constraint for further expansion is water. The current shrublands survive on mountain runoff from nearby highlands. Moving deeper into the desert would require water resources that are increasingly scarce. Additionally, while desert sands may naturally trap roughly 1 million tons of carbon annually through temperature-driven expansion and contraction, photosynthesis remains the more dominant force.

The study concludes that while desert greening is not a singular solution to the climate crisis, it remains a vital piece of the puzzle. It serves as a proof-of-concept for low-tech carbon solutions and demonstrates that, with long-term planning, even the most inhospitable landscapes can contribute to environmental restoration.