Trochlear dysplasia is a common abnormality of the knee. Sometimes it causes severe symptoms. Still, a strict definition based upon objective criteria and biomechanical studies studies is missing

When and how to treat it are debatable. This article summarises the trochlear dysplasia condition, where are we and what comes next

Aspects of trochlear dysplasia

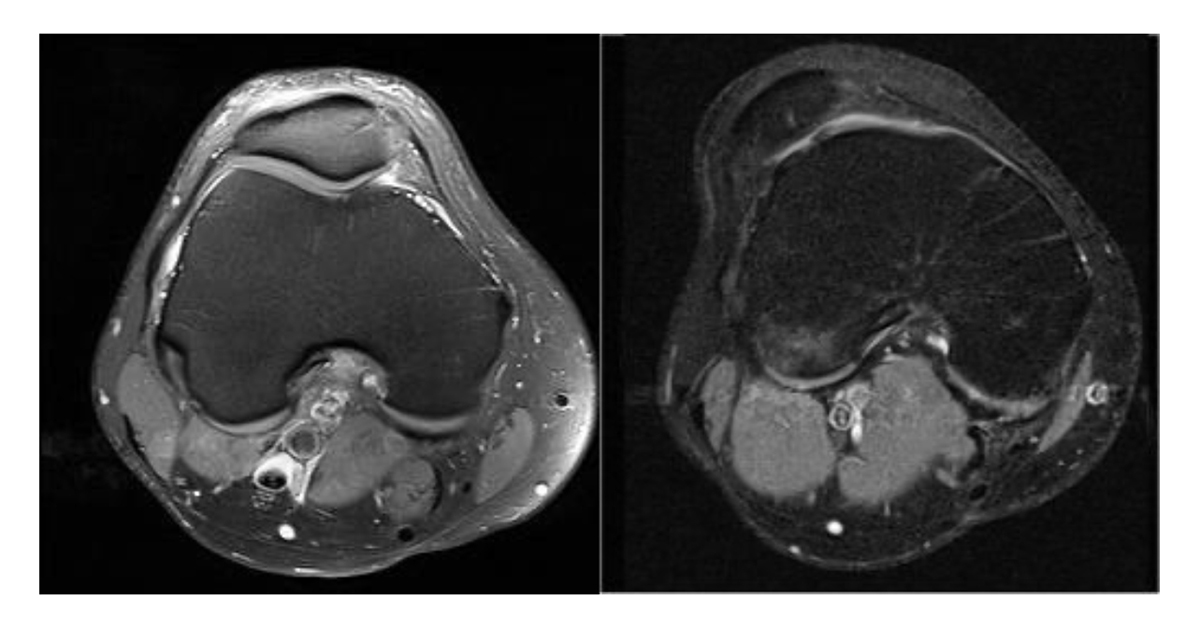

Trochlear dysplasia (TD) is an abnormality of the knees trochlear groove. There is an invisible transition between what is normal and what is pathologic. The knees trochlear groove is the guide channel, into which the patella engages and glides. TD is characterised by a loss of the normal concave anatomy: the depth of the groove is reduced, and also the configuration might be changed. Typically, a shallow, flat, or even convex trochlea is seen and most importantly, the TD is localised in the most upper end of the trochlea. The TD configuration can cause the patella (kneecap) to tracks abnormal – see figure. Think of the patella as a bobsleigh. If the bobsleigh does not track correctly, it will hit the wall and the paint will wear.

Analogous TD predisposes to cartilage wear, pain and osteoarthritis. If the tracking goes completely wrong, it will leave the run and crash, like when the patella dislocates. TD is the most important predisposing factor for an unstable kneecap. TD is not a disease and most individuals who have this abnormality, are asymptomatic and as such, TD is a condition. The higher the degree of TD, the higher the risk of becoming symptomatic is, either by patellofemoral instability (PFI), patellofemoral pain (PFP) or patellofemoral osteoarthritis (PF OA). PFI is a major problem, and more disabling than the more well-known anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears1,2 and below 14 years of age, the risk of having a patella dislocation is higher than having an ACL tear. To experience a patella dislocation, having the kneecap sitting on the outer side of the knee is a painful and distressing event and about 23% will experience a new dislocation. While some of those do not get a new dislocation, many still suffer from the patellar instability feeling and persistent limitations1. There are other factors for PFI other than TD, however, approximately 50% of patients with PFI have TD3,4. 80% of patients diagnosed with TD have bilateral TD.

Among patients having pain behind or around the patella (PFP), there seems to be an overrepresentation of TD5-11. PFP relates to chondromalacia patella which means sick cartilage in the PF joint which like TD, in fact, might be asymptomatic. TD and chondromalacia12 and severe cartilage defects of the patella7,13-15 and isolated PF OA16-22 are related. There seems to be a link between PFP in adolescence and later development of PF OA23,24. Population studies have shown that the prevalence of isolated PF OA is 19% in patients with knee pain25. In patients having isolated PF OA, 55-80% of the cases have TD17,26.

Heredity or origin or aetiology to TD

Larger apes have a flat trochlea27, however, since humans are walking upright, we have become a little knock-kneed, as this brings the knee joints closer together and assists the upper body to be positioned above the centre of gravity for walking. The consequence is a lateral acting q-factor on the patella, and to compensate for that, humans have developed a deepening trochlea sulcus with a lateral trochlea slope to support the patella.

The first description of TD goes back to 1802 where Richerand describes three cases of patella dislocations and all with a lower lateral condyle that affects the trochlea shape28. Already at the start of the 20th century, doctors are aware that TD plays a major role in the origin of patella dislocation28, and for the years ahead, until MRI scans commence, the Roentgen era technique evolves and makes the foundation for the first classifications systems like the Dejour Classification that has been refined several times and today it’s mostly used as a 2-group classification29-31. Other subjective classifications have been reported, 32-34, but like the Dejour classification, they do not relate to biomechanics or objective measurable criteria. There is still no consensus on how to classify TD, but the tendency goes towards objective parameters like the LTI35, which has been refined to a two-image technique36. LTI relates to the osseous stability provided by the lateral trochlea slope and is considered the single most important factor to quantify TD37.

Numerous other measures objectify TD, such as a volume reduction38,39 by 3D MRI scans. Automatic classification based upon artificial intelligence seems to be the future for daily practice40-42.

The main theories about the aetiology of TD are hereditary due to genetic factors, or a result of stress stimulation of patella, either during foetal life because of knee position in utero (breech position) or eventually reduced patella/trochlea stress forces during growth. All theories seem possible and can coexist. There are many reports on families with TD28,43-45 and it has been related to a balanced translocation of chromosomes46. Ultrasound findings suggest a relationship between TD and breech position47-49. However, there is also a developmental theory that TD might be induced postpartum and this is supported by animal studies since TD can be induced50-54.

Importantly, it seems that TD can be normalised. In a study with patients below 11 years of age who underwent patella stabilising surgery, the TD had normalised at follow-up55. Often the question goes to the patella shape when TD is present and generally the results are conflicting56-59. In a recent MRI study, they were not able to find any correlation between patella shape and trochlear measurements60.

To understand TD, you must understand normal trochlea geometry, and many have analysed this, and there are minor variations concerning age and gender. The trochlea is composed of a medial and a lateral facet that forms the trochlear groove. The lateral facet is wider and more prominent. In the normal knee, the trochlear groove deepens more

distally and deviates slightly lateral relative to the anatomical axis of the femur61,62. Importantly, trochlear depth varies from proximal to distal, since with most proximal there is a flatter configuration (higher sulcus angle and lower lateral slope)62-64.

Closing remarks on TD

Another important point of issue is the trochlear difference of cartilage and bone configuration, also denominated cartilage/bone mismatch and that the cartilaginous sulcus angle is consistently higher than the underlying osseous sulcus due to thicker cartilage in the centre of the groove13,62,65,66-68. Since the articulation occurs between trochlea and patella cartilage, it seems logical to measure on cartilage.

The following characteristics are commonly seen when TD is present and those can be objectively quantified. A reduced trochlear depth and a reduced lateral trochlea slope are imperative. Medialization of the trochlea groove because of a facet asymmetry, hypoplasia of the medial femoral condyle and ventral prominence, are all findings associated with TD but are not always present.

A common finding in the physical exam indicating the presence of severe trochlea dysplasia is the J-sign, which refers to the shape of the patella tracking as the knee extends.

Mild grades of TD are present in 10-20% among everyone and in 5% there is severe TD69,70. Among patients with PFI, the prevalence of TD is approx. 60%3,71-74

When it comes to surgical treatment of TD, trochleoplasty is a surgical procedure that reshapes the groove towards a normal trochlea, and the indications and specific techniques are evolving. The first of such was the trochleoplasty-like procedure carried out by Lucas-Champonierre in 184843.

Please note: This is a commercial profile

© 2019. This work is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND.