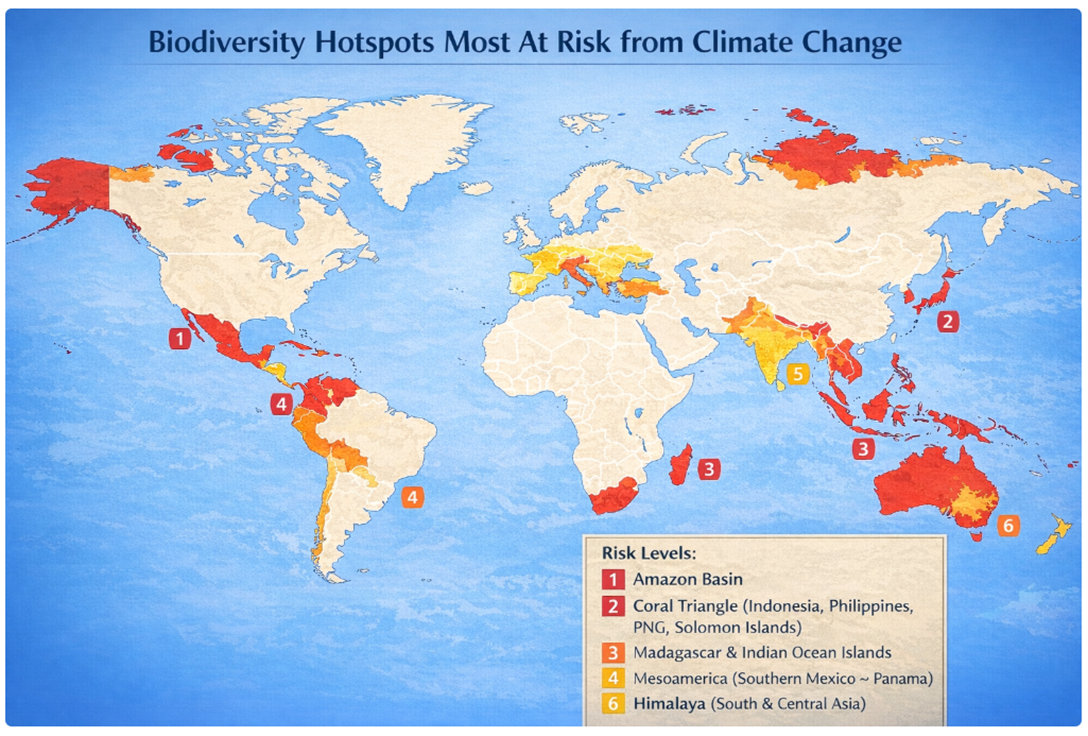

How climate infrastructure on Indigenous land can turn the next generation into solution-providers—while strengthening biodiversity stewardship and sovereignty

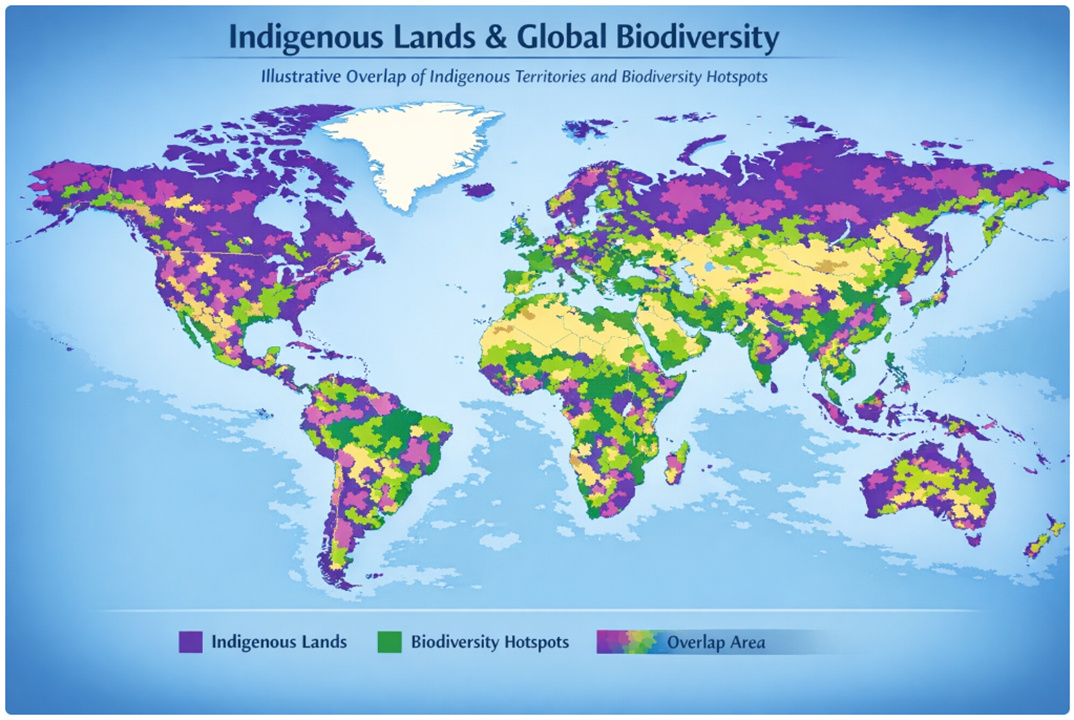

On maps used by planners, financiers, and ministries, many of the world’s most biodiverse landscapes appear as “remote,” “underutilized,” or “undeveloped.” On Indigenous maps—those carried in language, story, seasonal practice, and governance—these places are not blank spaces at all. They are living homelands: watersheds with names, animal corridors with obligations, fire regimes with rules, and sacred sites that carry distinct duties across generations. For the native people, serving and supporting the biodiversity is central to their existence on these Indigenous lands.

And, maintaining biodiversity is key to fighting climate change. This is because diverse ecosystems are more resilient and efficient at absorbing and storing carbon, regulating climate, and sustaining the natural processes that reduce greenhouse gas concentrations.

Indigenous knowledge systems

Indigenous peoples around the globe have historically managed and maintained biodiversity by using place-based, intergenerational knowledge—such as polyculture farming, controlled burning, seasonal harvesting, and respect for ecological limit—to work with natural systems rather than deplete them. Indigenous peoples steward roughly 25% of the world’s land, and protect roughly 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity. Land stewardship is part of Indigenous cultural “DNA,” that being encoded responsibilities transmitted through story, ceremony, law, and daily practice, living a life consistent with the famous proverb attributed to Chief Seattle ‘The earth does not belong to man; man belongs to the earth.’

This caretaking responsibility has been challenged by climate change. Indications of this are prevalent worldwide…from the North American Indigenous communities where flooding, wildfires, and water contamination have disproportionately affected reservations, many of which were historically located on marginal or environmentally vulnerable land due to forced relocation and colonial policies, to the Indigenous farmers and pastoralists in Africa who have experience increased droughts and erratic rainfall, disrupting traditional agricultural and grazing systems that have been refined over centuries, leading to food insecurity and conflict. And so many more…

Guardians of the land, victims of the crisis

Ironically, these global agricultural and pastoral communities, and others like them around the world, account for only a tiny fraction of historical greenhouse gas emissions that are causing the climate crisis we find ourselves in today.

So, the global communities who steward the majority of our biodiversity and a great deal of global land, are the same communities who have contributed the least amount to climate change, and yet these are the people who have suffered and will potentially suffer the most harm from the adverse and compounding effects of climate.

Interestingly, though, because of the land, agricultural and pastoral expertise of Indigenous communities together with a long history of faithful stewardship to the earth, the global Indigenous community may just be uniquely suited to implement workable solutions, bio-circular economies even, in an effort to avoid and prevent the worst of the impacts of climate change. True…Indigenous peoples are climate “first responders” by geography and history, not by choice. But with this impending crisis, the economic opportunities for these communities are also substantial, and can provide a well-deserved upside to the people of these Indigenous nations.

Designing climate infrastructure that serves the land

Some Indigenous communities may choose engineered approaches (e.g., mineralization, biochar systems, passive direct air capture systems). The rule should be that any engineered system must, at a minimum, be (1) non-toxic, (2) reversible where possible, (3) locally maintainable, and (4) biodiversity-positive or at least biodiversity-neutral.

A practical example might be certain climate dioxide removal technologies, which capture either point source, industrial or ambient CO2 and sequester that captured CO2 in the form of biochar, a valuable soil amendment for agriculture, and may in turn be converted into other valuable commodities, even for example, graphene or graphite, all while maintaining carbon neutrality or carbon negativity. The value added to the project through carbon offset credits, biodiversity credits, and others further amplifies project profitability and benefits to these Indigenous nations.

Leveraging such climate change solutions into viable business models that foster generational, bio-based circular industries and accompanying wealth on Indigenous lands represents a powerful win-win—namely, placing earth’s stewardship in the hands of those most likely to preserve it in the best way in the face of climate change, and in turn giving the opportunity for industrial progress and generational wealth in the hands of those who earned it through proper environmental guardianship of the earth.

No one would question native people’s reluctance about the adoption of new technologies on Indigenous lands based on the history of injustices, including land dispossession, racism, and social and economic marginalization. It is incumbent, therefore, that a new generation of regenerative, community-owned climate infrastructure be designed so that it (1) reinforces land and cultural stewardship, and in no case does it poison the land, (2) creates dignified, beneficial careers for young people, (3) generates durable, generational revenue for the Indigenous community, and (4) measurably improves economic and ecological outcomes.

Indigenous youth will be critical to the success of the implementation of climate mitigating technologies on Indigenous lands. If we embrace the stewardship maxim that we are “borrowing” the Earth from those not yet born, we gain a practical governance test: Would this project still make sense if the primary stakeholder were a child living here in 2050?

A “youth-as-solution-providers” model has three ingredients:

- Paid learning (not volunteerism as the default)

- Real tools (GIS, sensors, drones, lab partnerships, fire training, microgrid operations)

- Decision proximity (youth seats on stewardship councils, data governance boards, project design teams)

The effect is not subtle: if a generation of Indigenous youth is trained in and equipped for a new profitable industry (carbon dioxide removal, for instance) that’s serving the Indigenous intentions towards preservation and protection of the earth and its biosphere, the future is no longer something that “happens to you”. It becomes something “you build”.

The deal only works when the Indigenous people’s gains are not “co-benefits” but primary objectives. And in any case, exit options must exist: if a system fails or harms, it can be removed without financial punishment.

The future will be built somewhere. The question is whether it will be built on Indigenous land or with Indigenous Nations—so that the people most often described as climate victims are recognized, funded, and celebrated as climate solution providers. And with this background, as a design constraint and a moral compass, the teaching remains: we belong to the Earth.