Professor Iain Chapple from the University of Birmingham UK, explains the link between periodontitis and non-communicable diseases such as Type 2 diabetes

In 1990, the leading causes of non-fatal health loss in males and females, determined by years lived with disability (YLD) were oral disorders. The latest Global Disease Burden analysis of disability life years demonstrates that this remained the case in 2007(1). The global economic impact of dental diseases (principally periodontitis and dental caries) in terms of direct treatment costs are estimated at $298 billion, or 4.6% of global health expenditure, and indirect costs (i.e. productivity cost) equate to $144 billion which is within the range of the 10 leading causes of death globally(2).

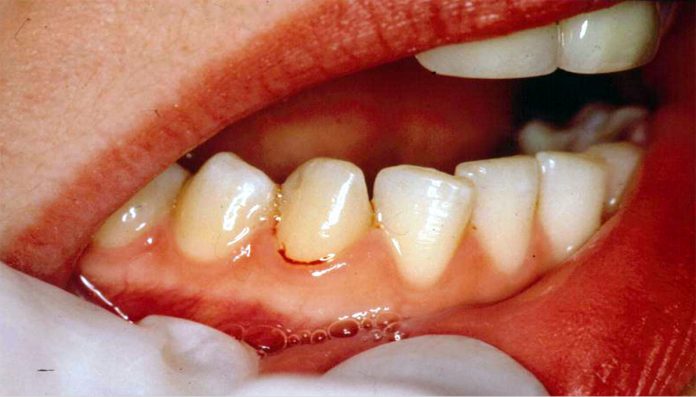

Periodontitis is a non-communicable disease (NCD) that afflicts 40-50% of adults worldwide, with severe periodontitis affecting 11.2% of adults, being the sixth most common human disease. Periodontitis is a major cause of tooth loss, negatively impacting upon nutrition, speech, self-confidence/esteem and quality of life.

However, it remains poorly reported in the medical world that periodontitis is also an independent and non-traditional risk factor for premature mortality (all-cause and cardiovascular mortality) as well as several systemic NCDs such as Type 2 diabetes (T2D), atherogenic vascular disease (AVD – cerebrovascular and cardiovascular), chronic kidney disease (CKD) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Periodontitis shares common risk factors with its sibling NCDs such as smoking, overweight/obesity, glycaemia/hyperglycaemia and stress.

Whilst this provides opportunities for the oral healthcare workforce to support WHO initiatives on common risk factor control, there is also robust evidence emerging that periodontitis is a co-morbidity for NCDs like AVD, T2D and CKD and that successful management of periodontitis can improve outcomes of AVD(3) and T2D (4).

The potential importance of periodontitis as a common but silent co-morbidity (Figure 1) was highlighted in a recent study by the Birmingham group, which demonstrated the co-morbid presence of periodontitis in CKD patients with stage 3-5 disease significantly increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. The impact of periodontitis was equivalent to that of the co-morbid presence of T2D in CKD patients(5).

Moreover, the multi-morbid presence of periodontitis, T2D and CKD further increased all-cause 10-year mortality by 23% and cardiovascular mortality by 16%. The group have also started to unravel potential mechanisms whereby periodontitis may add to the systemic inflammatory burden(6) through the activation of reactive oxygen species release by circulating peripheral blood neutrophils, as well as the activation of an acute-phase response (CRP). These are believed to arise due to the proven entry of periodontal bacteria into the circulation during eating and tooth brushing in those patients with periodontitis, with a dose-response between the severity of disease and magnitude of bacteraemia.

Such events, when arising multiple times daily over several decades are a cause of the chronic low-grade systemic inflammation in periodontitis sufferers and thus a biologically plausible mechanism underpinning the development and complications of complex diseases like T2D(7).

The strongest relationship between periodontitis and any NCD is with Type 2 diabetes, where a bi-directional relationship exists. The presence of hyperglycaemia in poorly controlled or undiagnosed diabetes strongly associates with a more severe and suppurative periodontitis, and the presence of periodontitis associates with an increased risk for developing T2D, poorer glycaemic control, dyslipidaemia and both microvascular and macrovascular complications of diabetes.

The evidence was recently reviewed systematically by a joint workshop between the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) and the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) and published simultaneously in the medical and dental literature(8). The joint EFP/IDF workshop produced evidence-based guidelines for patients attending medical and dental practices, as well as for medical and dental teams. Systematic reviews demonstrate that successful periodontal treatment can lower HbA1C levels by approximately 0.4% and a recent randomised controlled trial of intensive periodontal therapy demonstrated a 0.5% difference in HbA1C at 12-months between an intervention group and a control group(4).

Indeed, NHS England is developing a commissioning standard, which supports the recommendation that patients diagnosed with T2D are referred for a periodontal examination and any necessary treatment, and that oral health professionals play a role in early identification of diabetes. The health economic models indicate savings in medical care costs of up to £124 million if periodontal treatment in dental practice is optimised and a further £48 million savings if diabetes and pre-diabetes are identified early within dental settings.

Screening programmes for NCDs remain controversial, but NICE guidelines support the risk-driven early detection of diabetes in dental care settings. The rationale is that the public attend dental care professionals (DCPs) for “check-up’s” when they are healthy, thereby facilitating preventive programmes and behaviour change, whereas the majority of patients attend their medical practice when they have an ailment.

DCPs, therefore, access a different population to medical professionals and DCPs are experienced and successful in implementing preventive programmes(9). Given the 1 million undiagnosed cases of diabetes in the UK alone and 17 million undiagnosed cases in Europe, this would appear to be a missed opportunity, and one that merits further exploration. Are the public and professions ready for such a change?

A recent study from the Birmingham group sought the opinions of 2919 of the public in the West Midlands, alongside 222 healthcare professionals(10). 48% of NHS dental patients and 61% of private dental patients were in favour of being assessed for NCDs in dental practices, as were 75% of those questioned in community pharmacies. All stakeholders were broadly supportive of allied health professionals performing risk assessments for NCDs like T2D.

Interestingly, 28% (25%) of NHS (private) dental patients questioned had not seen their general medical practitioner (GP) in 12-months and 7% (5%) had not seen a GP in five years. Of these groups, 42% (NHS) and 63% (private) were in favour of NCD assessment in dental practices.

Given that dental care professionals access a different population to GPs; dental providers also access people who do not attend their GP regularly, and periodontitis is a sentinel disease for other NCDs like T2D, it would appear that it is time to put the mouth back into the body and encourage greater collaboration between dental and medical teams.

References

1 GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators, 2018. The Lancet, 392, pp 1789-858.

2 Listl S et al, 2015. Journal of Dental Research, 94(10) pp1355-1361.

3 Tonetti M, et al 2007. NEJM, 356, pp911-920.

4 D’Aiuto F, et al 2018. The Lancet, 6(12), pp954-965.

5 Sharma P et al, 2016. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 423(2), pp104-113.

6 Ling M et al, 2016. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 43, pp652-658.

7 Chapple ILC, Genco R, 2013. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 40, ppS106-S112.

8 Sanz M et al, 2018. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 45(2), pp1-12.

9 Barnfather K et al, 2005, BMJ, 331, pp869-872.

10 Yonel Z et al, 2018, BMJ Open, 8, 11, e024503.

Please note: this is a commercial profile

Professor Iain L C Chapple

Head of the School of Dentistry

Institute of Clinical Sciences,

College of Medical & Dental Sciences

The University of Birmingham

Tel: +44 (0)121 4665129

Sec: +44 (0)121 4665486

www.birmingham.ac.uk/staff/profiles/clinical-sciences/chapple-iain.aspx