Scientists, in collaboration with NASA, have finally solved the decades-long mystery of how the planet Jupiter heats itself

Using data from the Keck Observatory in Hawai’i, astronomers have created the most-detailed yet global map of the gas giant’s upper atmosphere, confirming for the first time that Jupiter’s powerful aurorae are responsible for delivering planet-wide heating.

Researchers created five maps of the atmospheric temperature at different spatial resolutions, with the highest resolution map showing an average temperature measurement for squares two degrees longitude ‘high’ by two degrees latitude ‘wide’.

The team scoured more than 10,000 individual data points, only mapping points with an uncertainty of less than five per cent.

Firstly, what is an aurora?

Aurorae happen when charged particles are caught in a planet’s magnetic field.

These spiral along the field lines towards the planet’s magnetic poles, striking atoms and molecules in the atmosphere to release light and energy.

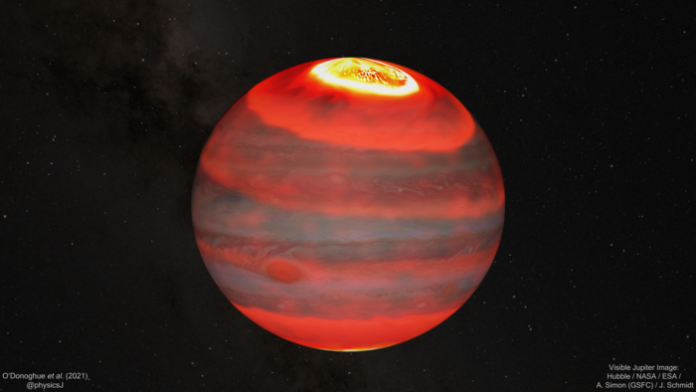

On Earth, this leads to the characteristic light show that forms the Aurora Borealis and Australis. At Jupiter, the material spewing from its volcanic moon, Io, leads to the most powerful aurora in the Solar System and enormous heating in the polar regions of the planet.

‘Jupiter’s aurora’ seems to be ‘heating the whole thing’

Dr James O’Donoghue is a researcher at JAXA and completed his PhD at Leicester, and is lead author for the research paper. He said: “We first began trying to create a global heat map of Jupiter’s uppermost atmosphere at the University of Leicester. The signal was not bright enough to reveal anything outside of Jupiter’s polar regions at the time, but with the lessons learned from that work we managed to secure time on one of the largest, most competitive telescopes on Earth some years later.

“Using the Keck telescope we produced temperature maps of extraordinary detail. We found that temperatures start very high within the aurora, as expected from previous work, but now we could observe that Jupiter’s aurora, despite taking up less than 10% of the area of the planet, appear to be heating the whole thing.

“This research started in Leicester and carried on at Boston University and NASA before ending at JAXA in Japan. Collaborators from each continent working together made this study successful, combined with data from NASA’s Juno spacecraft in orbit around Jupiter and JAXA’s Hisaki spacecraft, an observatory in space.”