Stephen F. O’Byrne, Shareholder Value Advisors, examines the objectives of executive compensation and how to measure them

The basic objectives of executive compensation have been the same since the rise of large companies in the late 19th century: provide strong incentives to increase shareholder value, retain key talent and limit shareholder cost. What’s changed over time is the dominant approach to achieving these objectives. In the first half of the 20th century, companies relied heavily on fixed sharing to achieve the three objectives. Since then, public companies have shifted their focus from fixed sharing to competitive pay in the labor market.

In 1922, General Motors (GM) adopted a bonus plan that made the bonus pool, which covered all cash and stock incentive compensation at GM, equal to 10% of profit in excess of a 7% return on capital. GM used this formula unchanged for 25 years and used the basic concept for 65 years. Fixed sharing remains the dominant approach to management compensation in investment funds such as hedge funds, private equity, and venture capital.

Achieving the three basic objectives of executive compensation

The conventional wisdom at public companies now is that they can achieve the three basic objectives of executive compensation if they have a high percentage of pay at risk and set target pay at the median of similarly sized companies in the same industry.

The theory is that a high percentage of pay at risk will give managers a strong incentive, not letting target pay fall below the 50th percentile will retain key talent, and not letting target pay rise above the 50th percentile will limit shareholder cost.

The problem with the conventional wisdom is that competitive pay policy – that is, setting target pay at the 50th percentile regardless of past performance – creates a systematic performance penalty that undermines alignment and incentive strength. When the stock price doubles, maintaining target pay at the 50th percentile requires a 50% reduction in grant shares to avoid exceeding 50th percentile pay.

Competitive pay policy makes a key component of executive wealth – the present value of expected future pay – completely insensitive to current performance (because future grant shares and profit interests are adjusted to fully offset the effect of current performance).

The conventional wisdom is widely embraced (and endorsed by the major proxy advisors) because companies, compensation consultants, and proxy advisors accept percent of pay at risk as a good proxy for incentive strength and make no effort to measure the sensitivity of wealth or pay to shareholder return.

Executive compensation research

I have developed two measures of incentive strength, a fully comprehensive measure called wealth leverage and a more limited measure called pay leverage, and both these measures show that most public companies fail to provide strong incentives or achieve high alignment of relative pay and relative performance.

Wealth leverage is the ratio of the percent change in executive wealth to the percent change in shareholder wealth. Executive wealth is the value of the executive’s stock and option holdings plus the present value of the executive’s expected future pay. An executive who holds all of his or her wealth in company stock has wealth leverage of 1.0 because any percentage change in shareholder wealth results in an equal percentage change in the executive’s wealth.

In a 2010 paper in the Journal of Investing, INSEAD Professor David Young and I showed that ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson had wealth leverage of only 0.35 even though he had 74% of annual pay at risk. Tillerson’s wealth leverage was low because the present value of his expected future pay represented 73% of Tillerson’s wealth but had very little sensitivity to current performance (consistent with competitive pay policy).

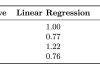

Pay leverage is the ratio of the percentage change in cumulative pay to the percentage change in cumulative shareholder wealth. Cumulative pay is calculated on a “mark to market” basis, taking into account the stock price at the end of each measurement period. Pay leverage is the slope of a regression trendline relating log relative cumulative pay to log relative cumulative shareholder wealth.

The slope is the percent change in cumulative pay associated with a 1% increase in relative shareholder wealth. The correlation is a measure of alignment, the intercept is a measure of performance-adjusted cost (the pay premium at industry average performance), and the slope divided by the correlation is a measure of relative pay risk.

U.S. public companies now report a five-year history of mark-to-market pay in their “Pay Versus Performance” disclosure. Using this data, I have shown that median pay leverage for a sample of 1,174 public company CEOs in 2020-2024 was only 0.51 and that relative TSR only explains 38% of the variation in relative pay for the median CEO. Pay leverage of 0.51 means that a 1% increase in relative shareholder wealth is associated with only a 0.51% increase in relative pay.

Pay leverage is a less comprehensive measure than wealth leverage because it doesn’t take into account changes in the present value of expected future pay beyond the five-year horizon.

It does, however, lead to a surprising insight about expected future pay when we realize that there is a simple pay plan with annual grants of performance shares that provides a perfect correlation.

How the perfect correlation pay plan differs from conventional practice

The perfect correlation pay plan differs from conventional practice in two ways. First, target pay must be market pay adjusted for trailing relative performance, not market pay regardless of past performance. Second, vesting must take out the industry component of the stock return. This requires that the vesting multiple must be 1/(1 + the industry return from the date of grant), not (1 + relative TSR), the vesting multiple commonly used.

The requirement that target pay be market pay adjusted for trailing relative performance means that future target pay will be affected by relative performance up to that date, including current relative performance. In other words, the pay leverage measure confirms what we learn from the wealth leverage measure – expected future pay needs to be sensitive to current performance for an executive to have a strong performance incentive.