Professor Julia Budka considers the potential of funerary archaeology for reconstructing life in New Kingdom Nubia, particularly on Sai Island

A well preserved Pharaonic settlement like Sai Island offers rich data of various quality and character to recreate a snapshot of everyday life in the New Kingdom Upper Nubia (c. 1539–1077 BC). Most importantly, not only the town of Sai is exceptionally well preserved, but in addition, several cemeteries of the New Kingdom period are located close by.

Combining data from settlement and funerary archaeology has much potential, not only for reconstructing daily life, health and diet but especially for understanding the ancient population, which is one of the main goals of the European Research Council (ERC) AcrossBorders project for Sai.

In addition to the analysis of finds and architecture from the settlement, the mortuary evidence helps to investigate the coexistence of Egyptians and Nubians on the island.

The location of Sai in a territory of strategic value with changing boundaries and alternating ruling powers in the Second Millennium BC (Egypt and Nubia) allows for the addressing of questions of ancient lives across borders and cultures. In general, there is still no common understanding regarding the social interconnections and power hierarchies of Egyptians and Nubians in Egyptian towns in Upper Nubia like Sai.

Entanglement, mixture and appropriation are currently thought to be highly relevant to understand the occupants and their complex identities.

Following the Sai Island example

Archaeological studies dealing with ethnicity, groups and identity have markedly increased in recent decades, reflecting the general popularity of these issues and current social debates. Theoretical models and the terminology used in archaeology were largely absorbed from sociology and anthropology, but in many cases, the archaeological evidence provides no clues on essential questions like the self-determination of individuals. At neighbouring sites of Sai, for example, Tombos and Amara West, studies of biological identities of New Kingdom people buried there were carried out recently (see Buzon 2008, Binder and Spencer 2014).

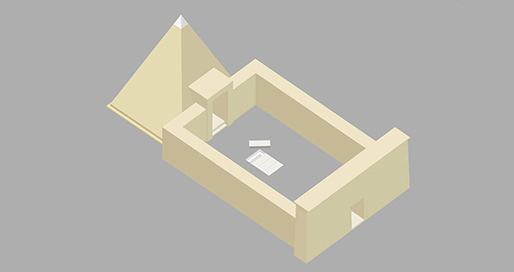

On Sai itself, the major New Kingdom cemetery SAC5 lies approximately 800m south of the Pharaonic town and was partly excavated by a French Mission. Some of the owners of the Pharaonic style tombs with rock-cut chambers, mud-brick chapels and mostly pyramidal superstructures are known by name thanks to inscriptions on funerary objects. These persons bear administrative or religious titles and appear to be Egyptians and/or Egyptianised Nubians.

The funerary equipment is of classic New Kingdom style and comparable with finds from other contemporary Nubian sites (e.g. Aniba, Tombos). Nevertheless, possible processes of adaptation and/or appropriation of the people buried in the New Kingdom tombs on Sai still need to be assessed. The ERC AcrossBorders project is therefore currently investigating whether projected images of the identity of the occupants of Sai differ, or are consistent in life and death.

AcrossBorders and Hornakht’s pyramidion

In 2015, a new Egyptian-type shaft tomb was discovered by AcrossBorders in the elite cemetery SAC5. This burial monument, Tomb 26, probably once had a pyramidal superstructure. The pyramidion (a capstone for a small mudbrick pyramid) of a high official of the Egyptian administration of Dynasty 19 with the name Hornakht was discovered in the shaft.

It remains open as to whether Tomb 26 was actually built by Hornakht, but the pyramidion with his name and title clearly attests his near-by burial. The burial monument was investigated further in 2016; remains of more than 10 individuals were excavated in the burial chamber, accompanied by typical Egyptian-style burial items, like scarabs and stone vessels.

Inside Hornakht’s pyramidion

However, we still cannot say whether we are dealing with Egyptian or Nubian individuals – but they all seem to have had an Egyptian cultural identity or were at least buried in an Egyptian way. That this is not necessarily reflecting the complete, complex picture of the past occupants of Sai may be illustrated by the example of Hornakht whose pyramidion was found in Tomb 26. According to textual data, he was likely to have been born in Nubia and probably belonged to a native community on Sai.

Completely Egyptianised by Dynasty 19, this family was on top of the local hierarchy and held the most important offices within the Egyptian administration. Consequently, as a high Egyptian official, Hornakht was buried in an Egyptian pyramid tomb, most likely with fully-Egyptianised burial equipment, which we still hope to partly recover in our currently ongoing 2017 season in Tomb 26.

The importance of studying material culture

Combining data from settlements and cemeteries promises a better understanding of past occupations and their cultural identities. The study of material culture and, here especially, of ceramics, is of prime importance, as are the human remains themselves. Scientific analyses of bones and dental tissue may represent additional tools to explore the origin of people and their migration along the Nile.

AcrossBorders is presently analysing the systematic variation in the isotopic composition of strontium in the environment of Sai, a method now widely used in archaeology, especially for tracing human and animal migration. The isotope map of the island will provide a basis for further interpretation of the autochthony or allochthony of the skeletal remains from Tomb 26.

References

Buzon, M. R. 2008. ‘A bioarchaeological perspective on Egyptian colonialism in the New Kingdom’, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 94, 165-182.

Binder, M. and N. Spencer 2014. ‘The Bioarchaeology of Amara West in Nubia: Investigating the Impacts of Political, Cultural and Environmental Change on Health and Diet’, in A. Fletcher, D. Antoine and J. D. Hill (eds), Regarding the Dead: Human Remains in the British Museum, British Museum Research Publication 197. London, 123-136.

Julia Budka

Professor of Egyptian Archaeology and Art

Tel: +49 89 289 27543

Please note: this is a commercial profile.