Stephen C Clark, from Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and University of Northumbria in the UK explains idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a type of lung disease

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is characterised by inflammation and fibrosis which develops as a consequence of taking certain drugs, inhaling antigens or as part of autoimmune connective tissue disease. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) has no identifiable cause and is the most aggressive form, typified by progressive lung fibrosis and inescapably worsening breathlessness as lung function declines, ultimately leading to death.

IPF has a yearly rate of three to nine per 100,000 with some regional variation due to environmental factors in Europe and North America with lower levels observed in Asia. The incidence has risen 78% over a decade in the United Kingdom.

Predicting disease progression is difficult (as baseline lung function is a poor guide) and it may take a variable course with acute life-threatening exacerbations.

Outcomes for patients are, therefore, poor with a median survival of two to three years from diagnosis which has not improved in recent years, though the impact of modern therapies awaits evaluation. Composite scoring systems which include both demographic and physiological data points may offer better prognostication, but the cause of death in 30–40% of patients is related to their co-morbidities, such as cardiovascular diseases.

Accurate diagnosis may be challenging. Surgical lung biopsy has a risk in those with poor lung function or advanced age. Biomarkers can be used from peripheral blood samples to detect specific proteins, for example, KL-6 which can discriminate IPF from other diseases.

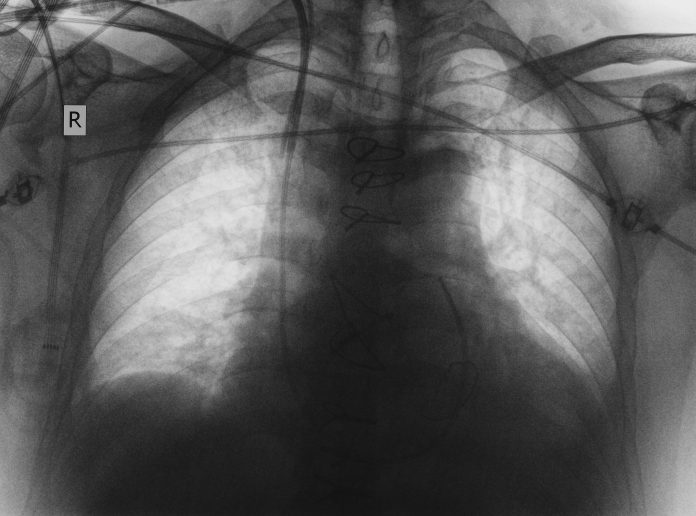

Radiological imaging with high-resolution CT scanning may show honeycomb cysts and subpleural reticulation but is not perfect. Newer technology including cryobiopsy as a surgical alternative and computer-based CT image evaluation (data-driven textural analysis) and machine learning may improve the situation.

What causes it?

Genetic predisposition and environmental factors lead to the activation of aberrant repair processes involving numerous inflammatory and profibrotic pathways in multiple cell types within the lung. Epithelial cells likely become highly susceptible to recurrent micro-injury from dust, cigarette smoke, environmental infections and viruses or gastro-oesophageal acid reflux.

As fibrosis becomes more severe, the pressure in the arteries supplying the lung rises (pulmonary hypertension) and is associated with very poor survival.

What can be done to treat it?

There is no cure but two agents can be used to alleviate the effects of lung fibrosis.

First, Pirfenidone has antioxidant and antifibrotic effects. It can slow the decline in lung function and disease progression compared to placebo, quality of life is improved and hospitalisations are reduced.

Second, Nintedanib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor which hinders lung fibroblasts and significantly reduces functional decline.

The INJOURNEY trial investigated both drugs used in combination but side effects such as nausea were increased. The INSTAGE trial combined Sildenafil to lower the pulmonary artery pressure with Nintedanib but to no avail.

Research is now focussed on the development of novel agents targeting fibrosis pathways or antibiotics to alter the lung microbiome. The latter is important as we now understand that acute deteriorations are associated with increased bacterial load or pathogenic organisms.

Future efforts are directed towards personalised therapy through biomarkers that can guide diagnostic, therapeutic and prognostic approaches.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Lower daily physical activity is associated with worse survival rates. Rehabilitation is, therefore, fundamental and includes nutritional advice and psychological support. Functional improvements in exercise capacity are very quickly demonstrable with no adverse effects but are not sustained into the long-term.

Palliative care

As the disease is invariably progressive and fatal the early management of symptoms to improve or maintain quality of life is essential. Symptoms such as cough, breathlessness and anxiety can be effectively managed often with opiates. Oxygen therapy at home has little objective benefit to offer but may improve exercise tolerance in some.

Lung transplantation

Transplantation is appropriate in those without co-morbidity. Patients up to 65-70 years of age may be considered as outcomes are good. As disease course is unpredictable and trajectory can alter rapidly early referral for evaluation is essential for potential candidates.

The shortage of donor organs means that many IPF patients will still die on the lung transplant list. The U.S. lung allocation score (LAS) prioritises patients according to IPF severity and likely post-transplant survival. A similar system exists in the United Kingdom. This has substantially increased the number of transplants in patients with IPF and has shortened the waiting time.

Bilateral lung transplantation is the preferred operation with a median survival of five to six years and 10-year survival of around 30%. Single lung transplantation remains a good alternative but is associated with 12% less survival at five years.

ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) can be used in those deteriorating on the waiting list. This technology oxygenates the patient via an external circuit and oxygenator to await a lung transplant. This is better than transplanting from mechanical ventilation.

Conclusions

IPF remains an irreversible disease which challenges patients and physicians with its unpredictable course and acute exacerbations leading to death.

The pathophysiology is better understood and has suggested several targets in the inflammatory/fibrotic pathway for future therapeutic research and biomarkers to personalise diagnosis, prognosis and guide therapy.

Pirfenidone and Nintedanib have positive effects but for many, pulmonary rehabilitation and palliative care are the inevitable pathways for those unsuitable for lung transplantation.

This remains the best option for those accepted but the donor organ shortage has led to prioritisation systems which favour IPF patients. The use of ECMO can usefully bridge the sickest patients to the transplant they need.