Steve Jones, Chair Action for Pulmonary Fibrosis and Board Member EU-IPFF and Gisli Jenkins from Nottingham University Hospitals, explain idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), an incurable lung disease

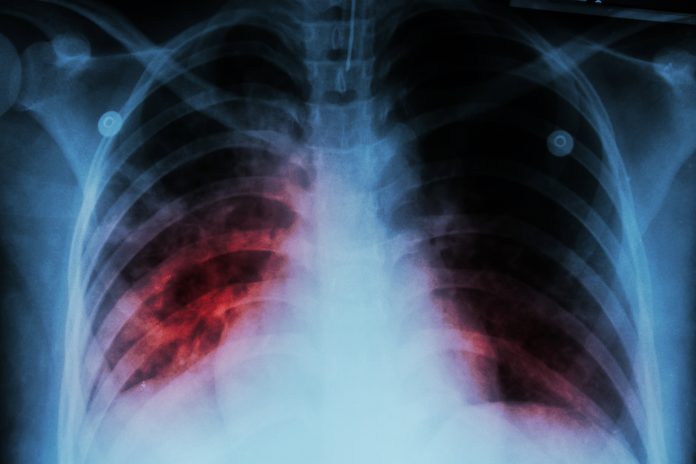

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), is an incurable lung disease in which scars are formed in the lung tissues. It is a devastating condition characterised by increasing breathlessness, disability and death three to four years after diagnosis. Only 25% of people survive for five years. IPF has a worse prognosis than most cancers.

Over 30,000 people in the UK live with IPF and over 5,000 people a year die from IPF. It is remorseless and the fourth biggest respiratory killer after lung cancer, COPD and pneumonia. IPF kills more people in the UK than leukaemia, but few people have heard of the disease. It generally occurs in people over 50 years of age and affects men more than women. Unlike many respiratory diseases, it is spread evenly through all sections of society.

We do not know the precise cause of IPF, but scientists believe it is triggered, in people with a genetic precondition, by exposure to cigarette smoke, dust and pollution. Acid reflux from the stomach may also play a role. Similar progressive fibrotic diseases, where the cause is known to include asbestosis and farmer’s lung disease. Epidemiological research indicates that the incidence of IPF is increasing rapidly at 2-3% annually. The reason for this is not clear.

Inequalities in care and treatment

IPF generally starts slowly and patients often receive treatment for other conditions, such as chest infections, asthma and heart failure, before they get the IPF diagnosis. GPs misdiagnose up to 35% of patients, which delays referral to hospital respiratory specialists.

Long NHS waiting times for hospital appointments also delay diagnosis and treatment. Fewer than 50% of patients get the diagnosis within six months of their first visit to their GP and for 20% of patients, it takes over two years.

Although IPF has such a poor prognosis, patients do not receive the same level of care as cancer patients. Cancer patients have a clear pathway designed to ensure timely and accurate diagnosis and treatment. They must start treatment within 62 days of a GP’s referral and are provided access to a specialist nurse. The timeline for IPF patients is less strict – patients only have to be seen by a hospital doctor within 18 weeks. IPF patients who attend one of the 23 specialist centres in England generally have access to a specialist nurse, but this is often not the case at district hospitals.

Two anti-scarring drugs are available, which slow down the progress of the disease. These are expensive and have a number of side effects. The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has approved anti-scarring drugs for use with patients with a lung function criteria (force vital capacity between 50% to 80% of predicted value). This means that the drugs cannot be prescribed to early-stage patients with a lung function of over 80%. This restriction is of great concern to patients and their families. The UK is the only country in Europe where this is the case. In other countries, patients may be prescribed these drugs immediately after diagnosis.

As well as anti-scarring drugs, people with IPF may be offered pulmonary rehabilitation (involving exercise classes and education), cough suppressants and oxygen therapy to help alleviate some of the severe symptoms such as fatigue, cough and breathlessness associated with IPF.

As the disease takes hold, patients become more and more breathless. Initially, they are unable to climb stairs and eventually find walking on the flat difficult. They become dependent on supplementary oxygen. Their world closes in on them and they feel isolated.

Patient support groups can play a vital role in helping patients and their families overcome this feeling of loneliness and find support. They also provide an opportunity for patients to learn more about the disease and feel empowered to manage it better. Support group are generally run by patents and health care professionals, such as nurses or physiotherapists.

Patient charities, such as Action for Pulmonary Fibrosis, in the UK, have galvanised the community by raising money, funding research, helping to set up over 75 local support groups and providing educational resources for patients, carers and healthcare professionals. Similar patient organisations exist in other European countries, the U.S. and Canada.

Hope for the future

Despite the grave prognosis, there is considerable hope for patients with IPF. There are a large number of new anti-scarring drugs being developed to treat this condition. Furthermore, new genetic insights into the disease have raised the prospect of precision medicine using targeted treatments tailored to patients with specific genetic or molecular abnormalities.

Artificial intelligence (AI), as well as wearable and other smart technologies, may help identify patients earlier, who may then gain more benefit from starting these new or conventional therapies sooner.

Although IPF is a deadly disease and is killing more and more people each year, increased collaboration between doctors, scientists and patient advocacy groups is leading to real improvements in outcomes for patients with this devastating disease. This is happening in the UK, across Europe and globally (see box).

The main challenge facing policymakers, in the years ahead, will be to ensure adequate funding for research on IPF and to pay for costly new treatments needed for rising numbers of IPF patients.

A European Patient Charter on best practice in IPF care and treatment

The European Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Related Disease Federation (EU-IPFF) was set up in 2013 by patient advocacy groups from different countries and leading clinicians to launch a European Patient Charter on best practice in IPF care and treatment. Since then, it has grown into an important platform for sharing best practice, educating its members and raising awareness among policymakers in the European Parliament and European Commission.

The EU-IPFF promotes the collective partnership of patient groups, health care, professionals, academia and industry. Larger groups in which it is active, such as the European Lung Foundation, Eurordis (Rare Disease Europe) and the European Reference Network on Rare Respiratory Diseases (ERN-Lung), in turn, support EU-IPFF. It has a Scientific Advisory Board comprising leading clinicians and scientists from across Europe.

A benchmarking study of IPF care and treatment across Europe, which highlights areas for improvement in different countries has recently been completed by the EU-IPFF. In 2020, it will organise the first European IPF Patient Summit on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and interstitial lung diseases (ILDs). This will bring together patient groups, healthcare professionals and industry representatives to discuss research, person-centred care, policy and advocacy for IPF and ILDs.

References

- Ley, B. et al. 2011. Clinical Course and Prediction of Survival in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory Critical Care Medicine. Vol 183. Pp 431-440.

- British Lung Foundation. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Statistics. https://www.blf.org.uk/support-for-you/idiopathic-pulmonary-fibrosis-ipf/statistics. Last accessed 2nd September 2019.

- Cancer Research UK. Cancer Statistics by type – Leukaemia. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/leukaemia. Last accessed 2nd September 2019.

- Hutchinson, J. et al. 2014. Increasing global mortality from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the twenty-first century. AnnalsATS Volume 11, Number 8, pp 1176-1185.

- Action for Pulmonary Fibrosis. 2018 Patient Survey – Giving Patients a Voice. https://www.actionpulmonaryfibrosis.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/APF-Report-Final-070319-crop.pdf. Last accessed 2nd September 2019.

- Action for Pulmonary Fibrosis. 2018 Patient Survey – Giving Patients a Voice. https://www.actionpulmonaryfibrosis.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/APF-Report-Final-070319-crop.pdf. Last accessed 2nd September 2019.