Better understanding of the factors at play will enable efforts to reduce HIV transmission in Southern and Eastern Africa, where incidence rates are highest

The global HIV epidemic peaked at 3 million new infections in the year 2000. However, since 2010 the decline has stalled at 2 million new infections and 1 million deaths per year. HIV remains extremely unevenly distributed in the world. Half of all new infections, as well as deaths, occur among 4% of the world’s population living in just a few countries in Southern and Eastern Africa. New infections mainly occur through heterosexual intercourse, but transmission also varies more than ten-fold between population groups within these countries. We also see a clear feminisation of the HIV epidemic across Africa. To date, researchers still cannot explain these tremendous variations in heterosexual HIV transmission.

The prevalence of HIV is increasing among teenagers in the most affected countries in South Eastern Africa and the high number of new infections rapidly adds to the growing total in need of HIV treatment. This pushes the cost of antiretroviral drugs and the demand for care beyond the capacity of the meagre health systems.

Poverty and gender inequality can’t explain all

A key issue is the high incidence among young women who carry the largest burden – over 70% – of all new infections among adolescents in the most affected countries. Over past decades we have tried to understand the high HIV incidence among women in Africa using poverty and gender inequality lenses. Both aspects are major global challenges and clearly both relate to healthcare access, education and engagement in unwanted and risky sex among young women, but this not only true in South-Eastern Africa.

Poverty and gender inequality cannot explain the manifold variation in HIV transmission, between or within African countries. Equal or worse poverty rates and more pronounced gender inequality also exist in areas with much lower HIV incidence, such as in northern and western Africa.

We need to think outside the box to understand how historical, cultural and political factors, in combination with various modes of modernisation, may interact to create locally specific behavioural patterns of intergenerational sex, concurrent sexual partnerships and transactional sex. Sexual networks where both men and women have parallel partners fuel the epidemic because of the rapid spread when somebody in the network becomes newly infected and is unaware of his or her HIV-infection.

Early diagnosis is needed

Today’s highly effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) does not only enable long and healthy lives, but can also dramatically reduce the risk of transmission to sexual partners – so-called Treatment as Prevention, TasP. For TasP to work, people must get tested early, but 4 out of 10 are not aware they have HIV and thus cannot access ART. Late testers die untreated or only get access to ART once they become symptomatic, often a decade down the line. In the meantime, their partners are at risk of infection.

Although South-Eastern Africa is way ahead of the rest of Africa in terms of treatment access, 10 million of the overall 19 million estimated to be living with HIV in this sub-region have been introduced to ART. Still, the incidence of new HIV infections remains between 3 to 50 times higher in the South-East, as compared to Western, Central and Northern Africa. A reasonable conclusion is that many of the interventions based on testing and treatment do not work well enough when scaled-up to local contexts.

Local variance in HIV transmission

Aside from understanding why sexual risk behaviours prevail, new ways to increase the uptake of HIV testing are also vital. HIV stigma and conventional facility-based HIV services explain part of the unwillingness to test but should be possible to change. Role models living with HIV could reduce stigma. Easily accessible information about HIV adapted to mobile phones and social media is an underemployed mode of health communication that could lessen the fear among young target populations in south-eastern Africa, the majority of whom have access to mobile phones.

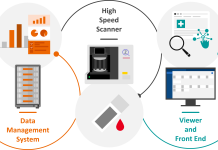

More individually adjusted and less stigmatising testing services – such as mobile health units attractive for teenagers and home-testing and self-test kits that could be ordered through the web or via SMS – should probably be explored much more, but we will never be able to entirely control the HIV epidemic through treatment solutions alone.

Further expansion of conventional interventions such as promoting condom use, postponing sexual debut or using ART as prevention will not work if we cannot understand the tremendous local variation in HIV incidence between and within African countries.

Professor Anna Mia Ekström

Senior Infectious Disease Consultant

Tel: +46 (0)73 6274884

Global Health, HIV and SRHR Research Group at KI on Facebook

Please note: this is a commercial profile